Seva Novgorodsev: The DJ who 'brought down the USSR'

- Published

Any list of the BBC's biggest radio DJs must include Seva Novgorodsev, famous all over the former Soviet Union for broadcasting pop music across the Iron Curtain and poking fun at the regime. On Friday, after 38 years on air, he hung up his headphones for good.

A mellow late-night-radio voice floats over the horn introduction to Stevie Wonder's Sir Duke. "Good evening and welcome from London," come the words in Russian. "Today we will focus on the most popular records of the week, both in Britain and the United States."

With those words, broadcast late in the evening on Friday 10 June 1977, Seva Novgorodsev began his career as the BBC's DJ for the Soviet Union. Over the next four decades, he would become an unofficial - and definitely unwelcome - ambassador for Western popular culture behind the Iron Curtain.

In the 1980s it's thought that 25 million people regularly tuned their shortwave radios to hear Seva's crackly broadcasts of David Bowie, Queen and Michael Jackson on the BBC Russian Service. The influence of these programmes, arriving at the end of the Soviet era, was enormous.

At that time, his four-letter first name was as well known in Russia as the three-letter name of the organisation he worked for.

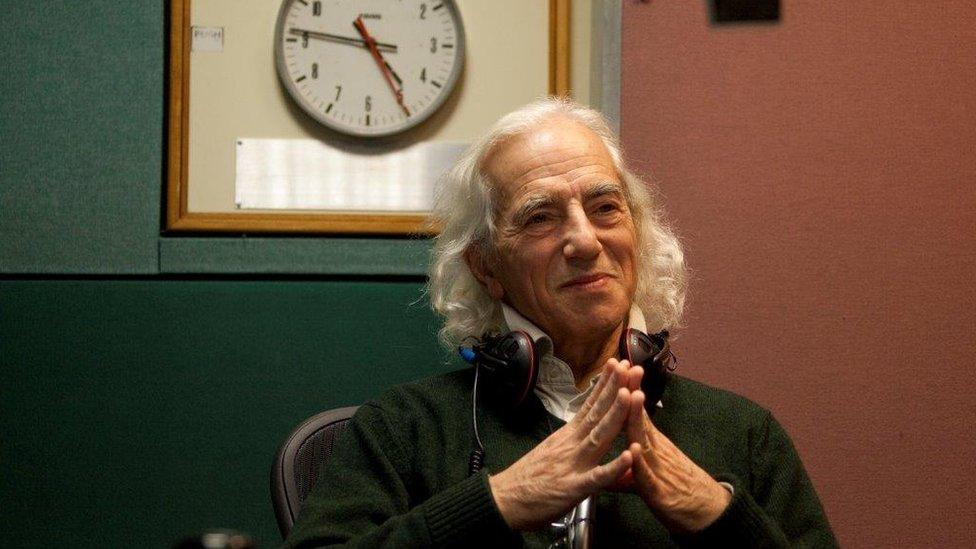

Always well dressed, with - latterly - a mane of white hair, Seva cut a striking figure in Bush House, the World Service's stylish but shabby HQ until 2012. But now, at the age of 75, he is retiring - his final show was on Friday.

When he left the Soviet Union, Seva was a successful jazz musician, who had learned the saxophone and clarinet at naval college. After paying 500 roubles each - about five months' salary - he and his wife were permitted to exchange their Soviet passports for pink exit visas in 1975.

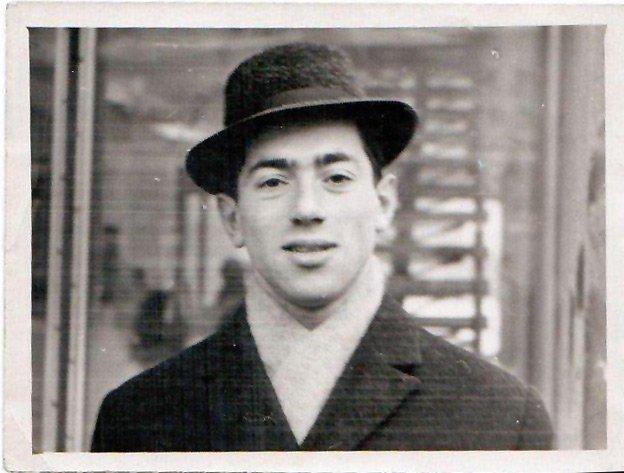

Seva in 1963

He came to the BBC in March 1977, joining a diverse group of Russian artists and scientists who found themselves translating news reports from English and reading them on air.

Seva's music show represented a different way of interacting with the audience. His chatty, improvised style was influenced by English-language presenters such as Terry Wogan and John Peel. But, to begin with at least, Seva's programmes were meticulously prepared and scripted. He timed the intros to all the songs he played and crafted links that fitted perfectly.

"Then gradually I started to insert some jokes," he recalls. "I knew that people were bored stiff in Russia, especially the young people, who were under oppression of their family, of the school, of their youth party organisation. And Russia is a huge country and especially in provincial places, life is excruciatingly boring."

The script from Seva's first show in 1977

He became known for his satirical word-play, which was perfectly captured in the names of his programmes. Some of these enlisted his first name, which literally means "crop". His music show was Rock-posevy - meaning both Rock Crops and Seva's Rock. His chat show, which began in 1987, was Sevaoborot - crop rotation. Both names poked fun at the Soviet obsession with news reports about agriculture and industry.

Beatlology was the name given to a series of 55 short programmes about the Fab Four - it was, he says, "a pun on a lot of unnecessary scientific papers that the Russians used to write, because if you had a degree it would add 30 roubles to your wages".

Then, from 2003, BBSeva, a daily current-affairs programme, was dubbed "News with a human face" - a reference to the slogan of the Prague Spring, "Socialism with a human face".

"By using these agricultural terms and injecting a lot of jokes from the 'official' vocabulary, I turned it inside out and showed everybody - without being malicious - that it's really funny and it's really ludicrous," he says.

"And this is what led to the liberation of the young people - when they saw the Soviet reality suddenly. In a funny light that was it - it was no longer a terrible beast, it was a little cat that you could stroke."

Even in the era of perestroika, the gentle teasing continued, though it was perhaps a coincidence that the arrival of Seva's wine-fuelled chat show Sevaoborot - which brought listeners a sort of on-air dinner party complete with interesting conversation - coincided with Gorbachev hiking the tax on vodka and razing vineyards.

This clip, from a 2007 documentary film about the World Service, shows Seva at work hosting a chat show

Seva's constant stream of light-hearted references to the banality of Soviet life, alternating with catchy Western pop songs, led to him being described on numerous occasions as "the man who caused the demise of the Soviet Union".

"Of course, it's kind of an exaggeration or hyperbole, but the thing is that there is some truth in it," says Andrei Ostalski, who was editor of the BBC Russian Service during the launch of BBSeva. By avoiding political diatribes, Ostalski says, Seva did not put his patriotic listeners on the defensive. Instead, he allowed appealing bits of Western culture, filtered through his Russian sensibility, to arouse his listeners' interest. "He was a symbol of this curiosity and the way it caused this great penetration of certain Western values into Soviet society, which was sort of deadly for the regime."

The Soviet Union jammed the World Service signal, but listeners could often hear it, if they searched carefully and located the bandwidth the KGB had left open to monitor the broadcasts. The signal was better in rural areas, so Seva's Friday-night show became an established curtain-raiser to weekends at the dacha in the country.

Seva says he later discovered that Soviet leaders were so worried about the influence of his broadcasts that they instructed TV producers to schedule big shows to run against Rock-posevy. Russian newspapers also published many critical pieces about him, which he assiduously collected in five box files with the title "Personal Fame".

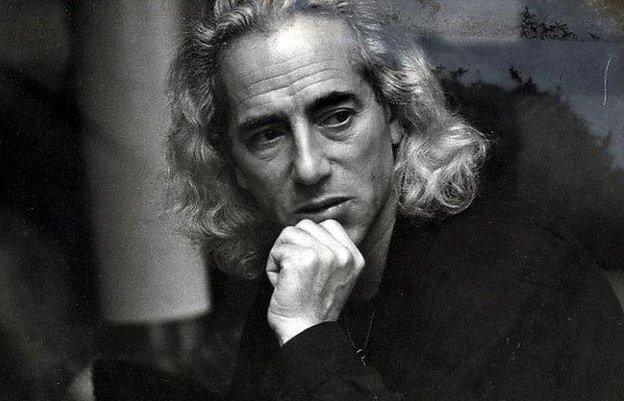

Seva Novgorodsev in 1990

But the correspondence that he received from fans forms a much larger archive.

Letters started to arrive in 1979, the envelopes practically oozing with the glue the KGB had used to fasten them down again after they'd been steamed open.

At least one listener, who Seva met years later, was jailed for writing to him. Others took greater pains to communicate on the sly. When the Soviet government, worried about the US missile programme, issued pro-forma letters for ordinary people to send to President Reagan appealing for peace, some listeners carefully copied the formatting of the letters, but changed the text to record requests and the address to Bush House.

Find out more

Listen to an English radio programme about Seva Novgorodsev, broadcast in Witness on the World Service

Watch a film about Seva in Russian

On one occasion, a Soviet sailor put a letter in a bottle and tossed it in the English Channel. The letter was just addressed - in barely decipherable Cyrillic - "BBC, Seva Novgorodsev" but somehow it found its target.

Seva kept all this correspondence and a few years ago donated it to the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The collection weighs 120kg and occupies more than 6m of wall space.

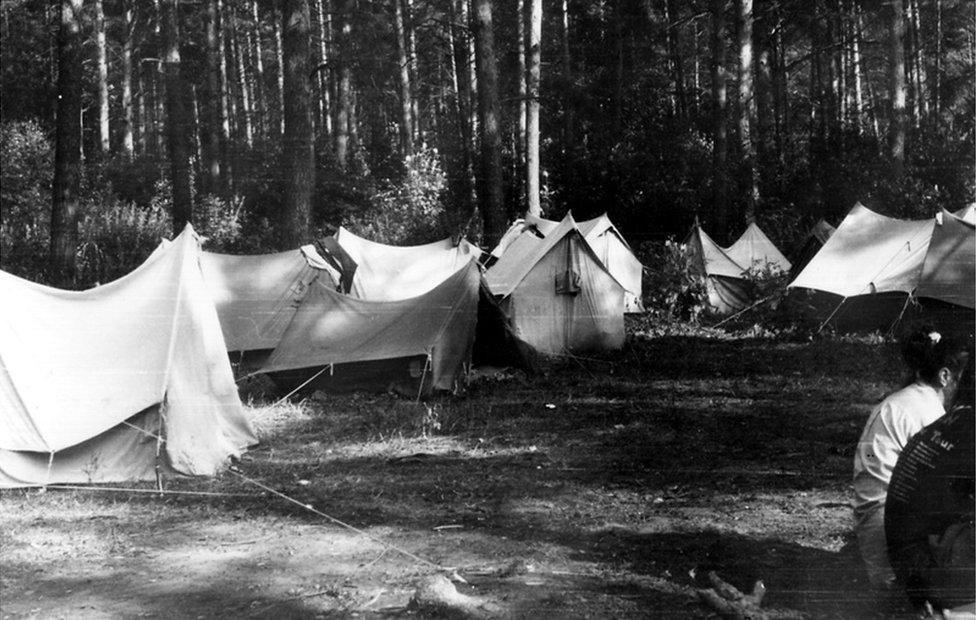

An early gathering of Seva's fans

In 1990, as the Soviet Union was starting to crumble, Seva went back to Russia. He was astonished to find about 800 people waiting for him at the airport, chanting "Se-va! Se-va!" His fans whisked him off to a tent city in the forest near Moscow, where, for several days, they kept him up until four in the morning with questions about music and his life in the West. It was the start of an annual tradition for Seva, who likes to meet his fans on his birthday, 9 July.

By this time, Seva had started taking on occasional acting roles. He had small parts in several films, including a baddie in the opening sequence of the 1985 Bond film A View to a Kill. In 1990 he also published a book of Russian recipes with his then wife.

"His fame was phenomenal. Walking with him in Moscow city would be impossible, because people would be asking for autographs all the time," says Ostalski. "And there was this annoying fact that he would so often get upgraded to business class when we were flying together somewhere."

Ostalski says that the extent of Seva's fame was not fully understood by BBC bosses. As the World Service became more focused on news, cutting much of its arts output, Ostalski championed Seva as a news anchor - one who would still have the freedom to tell jokes and share anecdotes.

Although today Western culture is easily accessible in the former Soviet Union, Seva - who was awarded an MBE in 2005 - believes that there remains a need for someone who can convey to ordinary Russians what life in the West is about, as he did for nearly four decades.

Seva is very proud of his MBE and wore it for his final broadcast on Friday

"I think the time has come again for us to communicate with our audiences any way that we can... to provide a human element of intellect, of talent - inject some spark - because people are starving for human information for something that will make their life lighter, easier. And by changing people from inside, we will change the society. I think it's the only way."

So what does he think about the idea that he not only changed Soviet society but helped bring it to an end?

"You know about these things in retrospect," says Seva.

"When you're doing it you're just little you, at your little desk, doing your little jokes."

Seva Novgorodsev spoke to Dina Newman for Witness on the BBC World Service. Listen again via iPlayer or get the Witness podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.