The women vanishing without a trace

- Published

Thousands of women and girls disappear in Mexico every year - many are never seen alive again. When one couple realised their daughter was missing, they knew they didn't have long to find her.

Elizabeth realised something was terribly wrong within 15 minutes of her teenage daughter, Karen, disappearing.

"I just knew it, I had an anguish that I'd never felt before. I searched the streets, called friends and family, but no-one had seen her," she says.

"She'd gone to the public toilets with nothing - no money, no mobile phone, no clothes… We thought she'd been kidnapped."

Karen disappeared in April 2013 when she was 14 - one of thousands of girls to have gone missing in recent years in Mexico state - a sprawling administrative region which wraps around the capital, Mexico City.

A staggering 1,238 women and girls were reported missing in the state in 2011 and 2012 - the most recent figures available. Of these, 53% were girls under the age of 17.

No-one knows how many have been found dead or alive, or are still missing. This is the most dangerous Mexican state to be a woman - at least 2,228 were murdered here in the past decade.

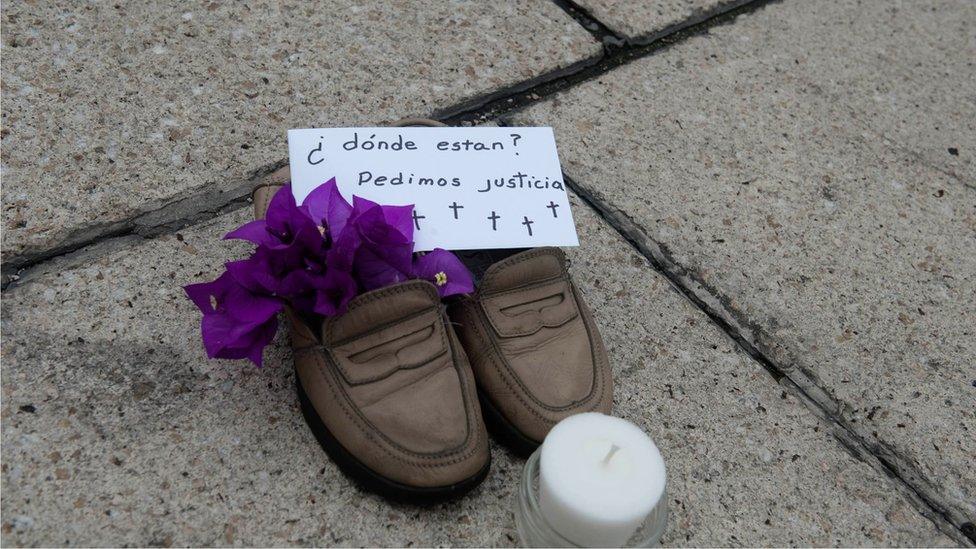

A pair of girl's shoes with the message: "Where are they? We ask for justice"

Elizabeth reported her daughter missing after three hours of frantic searching. But in Mexico police will not open a missing person's file until someone has been gone for 72 hours, not even for a child.

So, Elizabeth and her husband, Alejandro, started their own investigation, which began by going through their daughter's social network accounts.

"When we got into her Facebook account, we realised that she had a profile that we didn't know about, with more than 4,000 friends. It was like looking for a needle in a haystack, but there was one man who caught our attention. His was photographed with girls wearing very few clothes and big guns, and was friends with lots of girls about the same age as our daughter," says Elizabeth.

"This man rang alarm bells: he talked like a drug trafficker, about territory, about travelling, that he was coming to see her soon. He'd been in contact with her a few days before she disappeared, and had given her a smartphone so they could stay in contact, and we hadn't known," says Alejandro.

Each year it's estimated that 20,000 people are trafficked in Mexico, according to the International Organization for Migration. The majority are forced into prostitution. Authorities say a growing number are being targeted online.

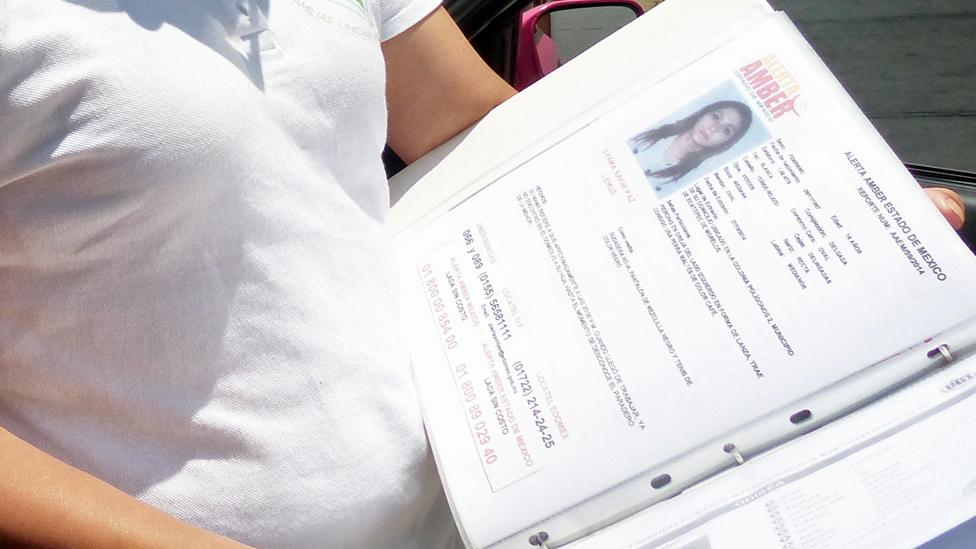

Karen's family realised they didn't have long to stop her being taken out of the country. They put pressure on the police to issue an "amber alert", and plastered official missing posters at every bus terminal and toll booth around Mexico City. They managed to get their daughter's case on television and radio news bulletins.

Their tenacity paid off. Sixteen days after Karen disappeared, she was abandoned at a bus terminal, along with another girl who was registered missing in a different state. The publicity had spooked their trafficker who was planning to take them to New York. He has never been caught.

"This man had promised her travel, money, a music career and fame. He manipulated her really well, and in her innocence she didn't understand the magnitude of the danger she'd been in," says Alejandro.

Elizabeth and Alejandro have a folder full of details of missing girls

At first, Karen was angry with her parents for ruining what she believed could have been her big break in the music business. So Elizabeth took her to a conference where she met girls who had been trafficked.

"It was when she heard their stories and realised what hell they'd been through that she finally realised the danger she'd been in. She went to the conference as one girl, and came back another," says Elizabeth.

Since Karen's return, Elizabeth and Alejandro have helped reunite 21 desperate families with their children. But they have a folder full of photos of others, some as young as five, who remain missing.

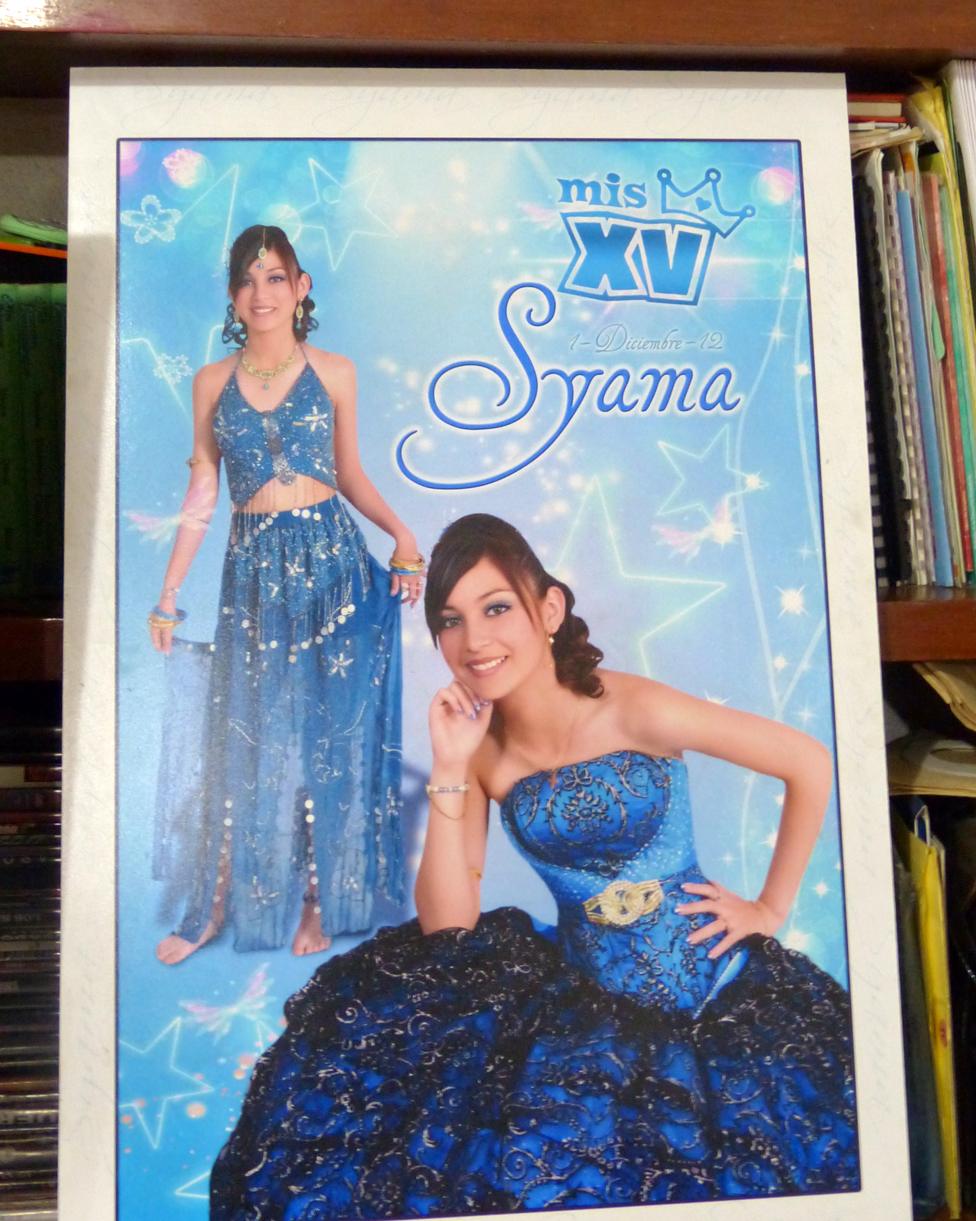

They drove me to the other side of Mexico state to meet one of them, the family of 17-year-old Syama Paz Lemus who disappeared in October 2014 - she was targeted online too.

The journey took us along the Grand Canal which runs through the state - the putrid smell of its filthy water is overpowering. Hundreds of bone fragments were pulled out of the canal last September, and so far several missing girls have been identified.

There is no national database of missing people in Mexico which makes the identification of remains difficult.

Remains of several missing girls have been found in the Grand Canal

While driving, Elizabeth received a distressing call requesting help in finding two sisters, aged 14 and three, who had disappeared while playing outside a few days earlier. The family sounded desperate, and Elizabeth promised to raise the alarm.

But this time she was unable to do much - the following day, she told me they had been found dead.

When we arrived at our destination, I learned more about Syama Paz Lemus - a shy girl who loved chatting on social networks and online gaming, she spent a lot of time in her bedroom on her laptop and Xbox.

It's a typical teenage girl's bedroom, with every wall covered in posters of bands and Japanese anime figures. Her dressing table is jam-packed with cosmetics and there's a TV and DVD player opposite the bed - now draped with a huge missing poster which her family take on marches.

Syama had seemed withdrawn in the fortnight before she disappeared, but her family assumed it was normal teenage behaviour so didn't press her for an explanation.

On the day she disappeared, her mother called her from work around 17:00 to make sure she'd eaten, but when Syama's grandfather returned at 20:00 she was gone. Her room was a mess and her Xbox and some clothes were also missing.

The neighbours said Syama opened the door to a hooded man who arrived in a taxi just after 17:00. Not long after, he led Syama out of the house carrying two bags, and the pair left in a white car.

Her mother Neida went online straight away but Syama's Facebook and Xbox accounts had been de-activated. She eventually found a secret folder showing screengrabs of online threats Syama had received in the weeks leading up to her disappearance.

"The threats were very direct: they said that if she didn't go with this person, her life would be made impossible, that they would publish her life on social networks, and that she and her family would regret it," says Neida.

"We always worried about her spending so much time online, but talked to her about the risks and had told her that she shouldn't give out information about herself."

Syama had left notes for her mother and grandparents. "She said that she would be OK, that we shouldn't worry, and that we shouldn't look for her. She asked me to look after her little sister, and buy her a present, so that she would always remember her," says Neida, breaking down in tears.

Since then, the family has searched for Syama in the hope of finding some clue to her whereabouts. They've traced unknown callers to Syama's mobile phone and chased anonymous tips around the country, but 10 months later there has been no breakthrough.

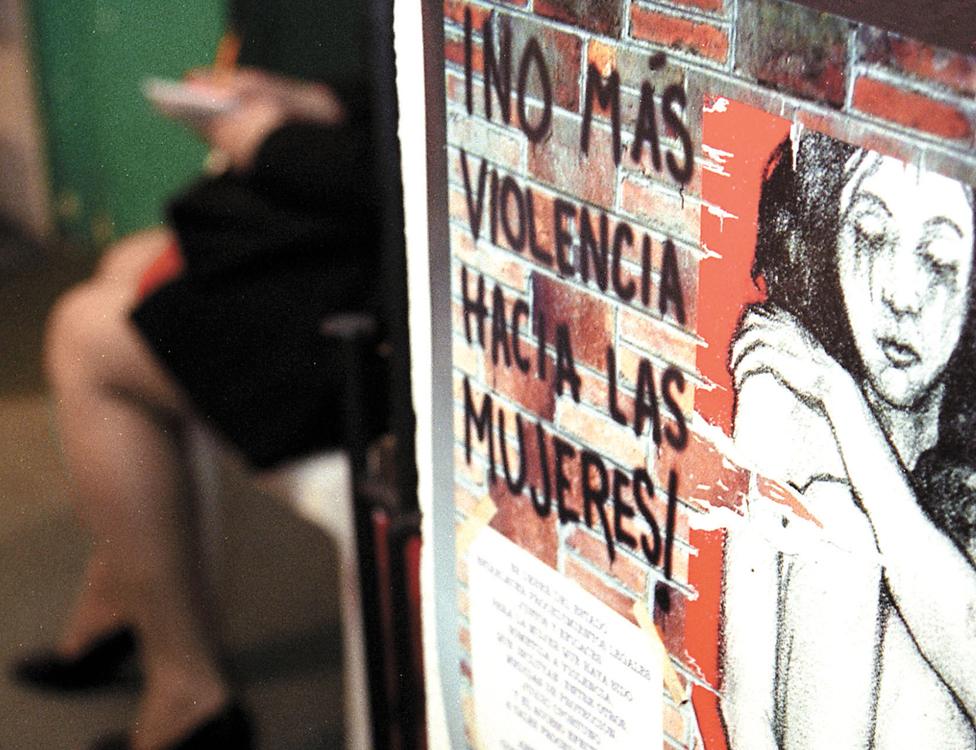

"No more violence against women"

In July, the state governor finally admitted - after years of denial - that gender violence is a serious problem in some areas. He issued Mexico's first ever "gender alert" in 11 of the 125 municipalities, including Ecatepec where Syama lived.

This means federal authorities must investigate the causes of the high levels of gender violence and then introduce emergency and long-term measures to protect women and girls.

Syama's case is still open with police, and her family remains optimistic. "Karen's story does give us hope that my daughter could return one day. But it's very hard, because you realise how unsafe it is here; you're not even safe in your own home."

Karen's name has been changed for this article

More on Mexico's missing

Many families in Mexico who have lost loved ones are now turning to social media for help, upset at the lack of official action. Thousands of people believe they have a better chance of finding missing relatives if they organise online searches themselves.

Nina Lakhani's report on the missing women of Mexico was broadcast on Outlook on BBC World Service. Listen to Outlook on iPlayer Radio.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.