The coming of the glacier men

- Published

When climbers go missing on high mountains it can be decades before their frozen remains are found in the snow and ice. But around the world, mountain ice is now receding. Does the rise in global temperatures provide hope to families who never had a body to say goodbye to?

"I'm always looking for things, or colours, that don't belong in nature, and you can see that quite often, crampons, rucksacks," says Alpine rescue pilot Gerold Biner.

"The east face of the Matterhorn is covered in stuff. I always say you could open a mountain shop with what's up there."

But two years ago, as he delivered concrete to a mountain hut in need of repairs, he noticed something different at the foot of the Matterhorn glacier on the mountain's north face.

A rescue helicopter over the Matterhorn

"I thought I saw something, and went for another look," he says. "And on the second fly-past I realised this must be a human being, exposed as the glacier was melting back."

It was the body of missing British climber Jonathan Conville, who disappeared on the mountain in 1979. In the 34 years that followed, Conville's body had travelled gradually downhill inside the glacier - and it appeared at the bottom edge of the glacier, where the ice melts into water.

September, coming at the end of the months of summer heat, is when ice cover is at its lowest, and it was in September last year - roughly a year after Biner's discovery of Conville's body - that the remains of two more climbers were found at the foot of the Matterhorn glacier, this time by another mountaineer.

After DNA testing they were identified last month as Masayuki Kobayashi and Michio Oikawa, both from Japan, who had gone missing in a snowstorm in 1970, nine years before Conville's death.

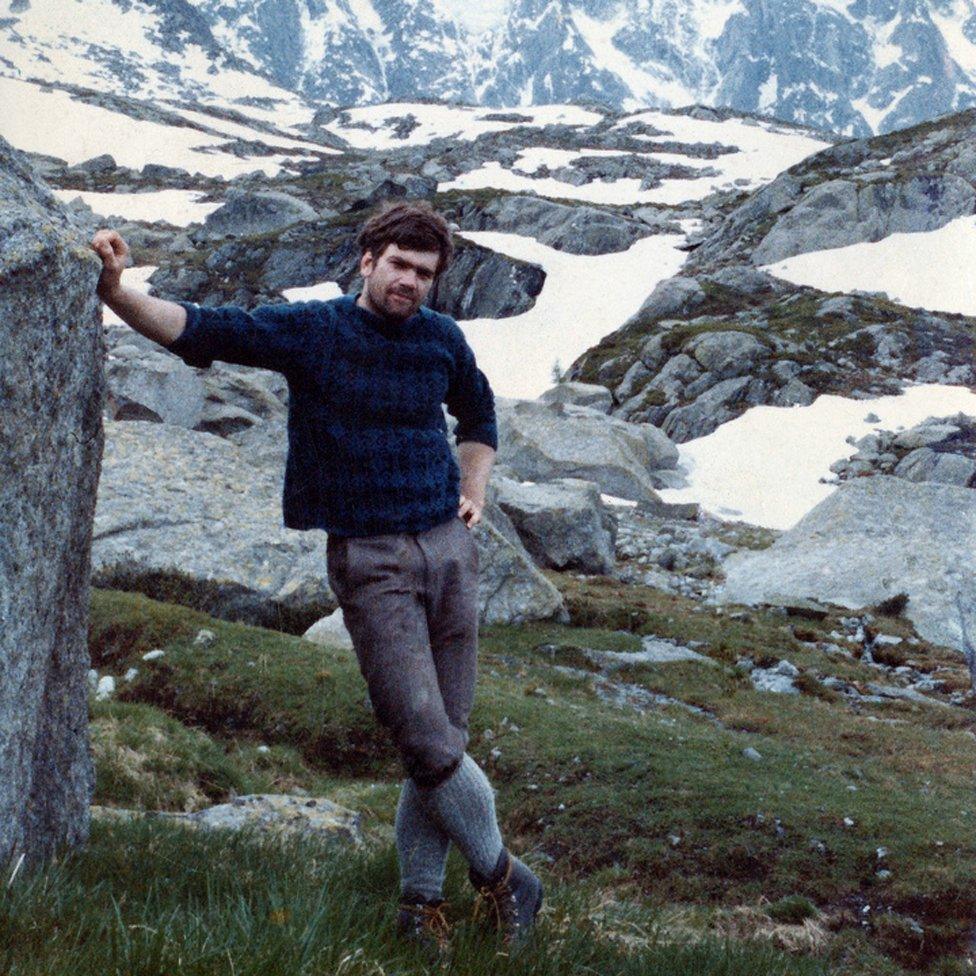

Jonathan Conville

A boot belonging to a Japanese climber who disappeared in the Swiss Alps in 1970

"More and more regularly the receding of glaciers permits the discovery of missing climbers after dozens of years," police said in a statement after the identities were made public.

The body of a French mountaineer, Patrice Hyvert, who had disappeared in bad weather near Mont Blanc in 1982 had been found a few weeks before the Japanese climbers, while the body of a Czech hiker, killed in an avalanche in 1974, was found in another part of the Swiss Alps a few weeks later.

All sorts of things have been retrieved from Alpine snow and ice over the years, from the remains of a crashed World War Two American bomber, to a cache of emeralds, rubies and sapphires being carried on an Air India flight which came down on Mont Blanc in 1966.

But over the last two decades the glaciers have retreated more rapidly, says Martin Grosjean, a glacier specialist at the University of Berne's Oeschger Institute. Even ice which has been permanent for thousands of years has started to melt, giving rise to a new scientific discipline - glacial archaeology.

Oetzi, the 5,000-year-old man found in the ice

As well as Oetzi, the mummified ancient man found near the border between Austria and Italy in 1991, 5,000-year-old items of clothing and household utensils have been found in the mountains south of Berne, shedding light on a Bronze-Age Alpine civilisation that was far more sophisticated than originally thought.

Hundreds of Roman shoe nails have emerged from the ice too.

"That is really interesting," says Grosjean. "Each shoe nail has a kind of a bar code, showing the year it was made, where it was made, and whether these shoes were used for military troops for the Roman army, or for civilian shoes."

Roman shoe nails found in the ice

All this raises the question whether an effort should be made to find climbers who went missing and whose bodies were never found. Rather than relying on hikers to report chance findings, or leaving it to the sharp eyes of air rescue pilots as they carry out their other duties, might it not make sense to carefully examine the foot of all Alpine glaciers in September, and the areas where ice is known to have been receding?

The number of people who have gone missing on the Matterhorn is dwarfed by the number who have died on it since 1865 - about 20 compared with 500 or 600. But that is just one mountain in the Alpine range. The number is 40 if you include other peaks around the resort of Zermatt, and 270 in the surrounding Swiss canton of Valais, the majority of them climbers, skiers, or hikers.

Lacking a body to mourn can add to relatives' distress by making it harder to accept that a loved-one isn't coming back.

"My mother would say, 'Oh, he didn't really die,'" remembers Jonathan Conville's sister, Katrina Taee.

As time went on Katrina says she began to hope her brother would not be found. "I felt it was a really lovely resting place for him, on a mountain. That would be bliss for him," she says. But her sister, Melissa, always wanted to find him.

Arriving in Switzerland to give DNA samples the sisters were able to hold their brother's mummified hand 34 years after his death, an experience Katrina has described as "bittersweet but wonderful".

Edward Whymper climbed the Matterhorn with Lord Francis Douglas

One family still hoping to locate the body of a relative missing on the Matterhorn is that of Lord Francis Douglas, who was a member of the first team to conquer the peak in 1865, but among four who tragically fell to their deaths on the descent.

All the bodies were quickly found, except that of Douglas, the son of the Marquess of Queensberry.

The current Marquess of Queensberry, the renowned designer David Queensberry, says the possibility his great-great-uncle might be found has "been in my mind all my life".

"My family has always thought there might be a chance he might pop out some day," he says.

Queensberry's 15-year-old grandson, Tybalt Peake, has plans to scale the Matterhorn next year with 78-year-old British climber Eric Jones, and is keen to search for Lord Douglas's body.

But Martin Grosjean argues that the chances of finding him are slim, because of the movement of the glacier at the base of the Matterhorn over the last 150 years.

Martin Grosjean explains how glacial ice moves

"Glaciers advance and retreat naturally," he says. "So at the top it's cold, snow falls. And then lower down, the ice melts. The glaciers flow naturally downhill, which means that everything that falls into a crevasse… later it appears in the glacier tongue."

The normal time span for anything trapped in an Alpine glacier to be washed out is, he suggests, between 20 and 50 years, though it can take up to 100 years. The recent examples of Conville, Kobayashi and Oikawa are broadly line with this - it was 34 years in one case, and 44 in the other.

"Well, we always have room for surprises," he says. "But, will we find Lord Douglas? I don't think so. If he was washed out it would have been about 1900."

Any organic matter is likely to have quickly decayed.

View across the Grosses Aletschgletscher glacier, Switzerland

When glacial archaeologists recover ancient bodies or artefacts from the mountains it's usually in areas where the ice is not moving, either because the ground is not steep enough, or the ice patch is not large and heavy enough.

There have been exceptions though. Martin Callanan of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology has written about Bronze Age arrow shafts that were recently recovered from a static part of a moving glacier.

"On the side of it was a small tongue that was not flowing, where the arrows were preserved and recovered almost complete," he says. "The icy world up there is terribly complex - just as complex as the landmass under with all its ridges, gulleys and crevices. We simply never know where and when ancient frozen remains are going to appear."

The Gorner Glacier near the Matterhorn (seen in the background)

As melting advances, the bodies of missing climbers, he suggests, could also emerge from parts of a moving glacier that have, for whatever reason, remained static.

But the idea of searching more systematically for climbers who went missing years ago gets little support from Gerold Biner or Katrina Taee.

Biner points out that the skies above the Alps are now busy with helicopters, and his hunch is that most bodies emerging from the ice are spotted.

And as Taee sees it, searching for human remains is of little importance, compared with searching for the living.

"At first of course you are desperate for them to found alive," she says.

"But you know anytime anyone goes up the Matterhorn it is very risky. Personally I wouldn't want anybody putting themselves at risk for my brother.

"Why risk lives for those who are long dead?"

More from the Magazine

It's a plot line that wouldn't be out of place in a Tintin comic - a French mayor, an Alpine climber, a historian, a wealthy Jewish stone merchant from London, and their tenuous connections to a bag of lost jewels discovered on the peak of Mont Blanc.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.