What's happening in a 20-mile set of roadworks?

- Published

The length of roadworks on England's major roads should be shortened, ministers have urged. What exactly goes on while highways are repaired and how can this be done while causing as few delays as possible?

You crawl for miles past an apparently endless procession of traffic cones. On the other side of them there's meant to be work taking place. Not that you can see any.

It's an all-too-familiar frustration for drivers on British A-roads and motorways. Figures released earlier this year suggested, external that one in three British car journeys was delayed by repairs.

But now there is the promise of some respite. Ministers want Highways England, which manages the roads, to shorten roadworks and lane closures. According to a report, external, works would be limited to two miles at a time, with a maximum of five miles in extreme cases.

The news would be welcomed by regular users of the M1 and M3 motorways, who currently have to factor in disruptions that last more than 15 miles.

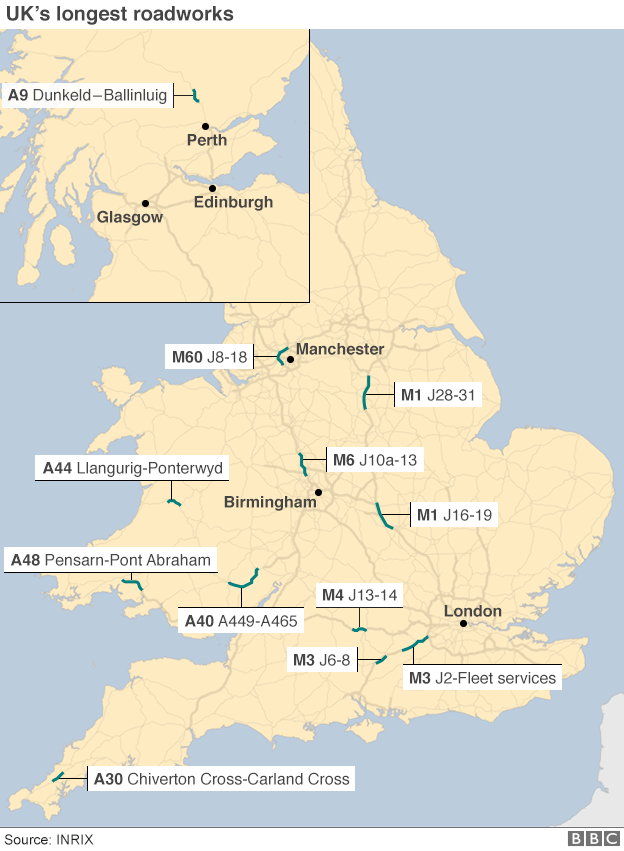

The UK's longest roadworks

An 18.1-mile stretch of narrow lanes and speed restrictions on the M1 near Chesterfield, between junctions 28 and 31

A 15.5-mile road improvement scheme on the M3, between junction 2 and Fleet Services, near Farnborough

Between junctions 16 and 19 of the M1 near Northampton, 13.7 miles of restrictions

On the M6, 9.2 miles of roadworks between junctions 10a and 13, near Birmingham

Source: Inrix

And England is likely to see a great deal more roadworks in the next few years due to a £15.2bn government programme to improve the road network which will see 80% of motorways and major A-road resurfaced and over 1,300 additional miles of highways. In Scotland a £3bn project will turn the major A9 artery between Inverness and Perth into dual carriageway.

With all this looming, there are calls for greater efforts to make repairs and upgrades easier for motorists. The AA says it wants to see overnight working wherever possible, repairs on motorways limited to stretches of 10 miles, more variable speeds limits and more incentives for contractors to finish on time.

But planning roadworks is already a fiendishly difficult process, requiring a huge amount of logistics and co-ordination.

It is also massively expensive. According to estimates, widening a 51-mile stretch of the M6 cost £1,000 per inch or over £60m per mile.

"To minimise the amount of work required you need to have better procedures," says Saad Yousif, senior lecturer in transport studies at the University of Salford. "You have to be co-ordinated."

Guidance for planning and operating temporary traffic arrangements is set out by the DfT in chapter eight of the Traffic Signs Manual, external, which runs to over 300 pages.

Roadworks can relate to fairly mainly minor issues - maintenance of signs, barriers, and lighting, for instance, or sometimes small drainage and resurfacing jobs.

But major work can be required when the road shows signs of deterioration or reaches the end of its design life, or when demand is higher than originally anticipated, which might require widening sections while traffic moves along adjacent lanes.

On a major road such as the M6 it's not practical to offer diversions, so the work has to be carried out while traffic continues to move along the road. Doing this means that even a small section becomes a major building site, says Yousif.

Safety barriers may have to be erected and access roads set up to allow equipment and materials to reach the work sites. Cones and temporary signage are put up - and secured in bad weather. Pipes and cables may have to be dug up and re-laid. The job becomes even more complicated when bridges or river crossings are involved.

Contractors planning works of these kinds have to think about how to keep vehicles moving as smoothly as possibly around the works. Computer micro-simulations might be used to model how this will operate in practice. In doing so planners will make reference to the fundamental diagram, external, which charts the relationship between traffic flow and density.

Research has suggested that the optimum speed limit around roadworks is about 50mph, says Yousif. When this is enforced properly - for instance, using average speed cameras - this increases capacity by reducing the need for lane changes (which slow down traffic), causing less turbulence and reducing accidents.

In recent years lanes have been narrowed from the usual 3.65m to 3m - but there are concerns that smaller gaps are unsafe and causing drivers to hesitate to overtake.

Planners, too, have to take account of driver behaviour. Modern motorists have more gadgets in their vehicles to distract them. It's been claimed, external that British drivers are too courteous - they are more likely to politely allow others to merge in front of them from a slip road, for example, which may force others to brake sharply.

A DfT spokesman said the proposals to limit the length of roadworks were "common-sense decisions to minimise frustrations wherever possible".

The move was welcomed by Steve Gooding, director of the RAC Foundation research charity, who said, external that "mile after mile of cones in one go might suit contractors but can drive motorists to distraction".

But while Richard Hayes, chief executive of the Institute of Highway Engineers, admits that contractors had not always taken drivers' views into account as much as they should, he cautioned against imposing "prescriptive" limits.

"I think you've got to look at the situation across the board and see what you're trying to achieve, and how the effect of what you're trying to do is going to have on the travelling public."

Because different jobs take different lengths of time to complete, contractors say it can be more efficient to block a longer section of road and plan the different works required within each section - laying pipes in the first mile, laying pipes, fixing drainage in the second, reinforcing overhead structures in the third and so on. But the downside is that this requires a huge team working in shifts and any delay by one team may result in longer delays.

Moving the site more frequently also results in higher traffic management costs and may affect overall safety and capacity.

It's "a matter of getting the right balance", says Steve Rowsell, vice-president of the Chartered Institution of Highways and Transportation. A nine or 10-mile limit would take 10 or 11 minutes to drive through "and that would seem to me to be something that drivers can tolerate".

Another possible solution is night working. But while this does minimises disruption to drivers, it isn't always possible with certain tasks that require greater visibility, says Yousif. Noise can also be a problem when the site is close to a residential area.

"Sometimes contractors don't have the capacity for 24-hour shifts," says Yousif. "It's good for the users but sometimes it's not possible especially as you are talking about specialist contractors, for instance those laying a safety barrier."

While reducing inconvenience to drivers is crucial, safety has to be paramount, says Yousif. The death rate for road workers is one of the highest for any employment sector reported by the Health and Safety Executive. A 2006 Highways Agency survey suggested that as many as 20% of road workers had suffered injury caused by passing vehicles and 54% had experienced a near miss with a vehicle.

The scourge of traffic cones will frustrate drivers as long as roads exist. But as technology improves and research into traffic flow develops, the sight of them may over time become a bit less irritating.

The Magazine on the motorway