Is the chilli pepper friend or foe?

- Published

For thousands of years, humans have taken a masochistic pleasure from adding chilli to their food. Now research indicates that the spice that has undoubtedly made our lives more interesting may also make them longer.

There is only one mammal that enthusiastically eats chillies.

"Humans come into the Western hemisphere about 20,000 years ago," says Paul Bosland from New Mexico State University. "And they come into contact with a plant that gives them pain - it hurts them. Yet five separate times, chilli peppers were domesticated in the Western hemisphere because humans found some usefulness - and I think it was their medicinal use."

The potential for both health and harm has always been a defining characteristic of chilli peppers, and among scientists, doctors and nutritionists it remains a matter of some dispute which prevails.

A huge study, published this summer in the British Medical Journal, seemed to indicate that a diet filled with spices - including chillies - was beneficial for health.

A team at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences tracked the health of nearly half a million participants in China for several years. They found that participants who said they ate spicy food once or twice a week had a mortality rate 10% lower than those who ate spicy food less than once a week. Risk of death reduced still further for hot-heads who ate spicy food six or seven days a week.

Chilli peppers were the most commonly used spice among the sample, and those who ate fresh chilli had a lower risk of death from cancer, coronary heart disease and diabetes.

One of the authors of the study, Lu Qi - who confesses that he is very keen on spicy food - says there are likely to be many reasons for this effect.

"The data encourages people to eat more spicy food to improve health and reduce mortality risk at an early age," says Qi, a nutritionist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, though he adds that spicy food may not be beneficial for those with digestive problems or stomach ulcers.

While the health-promoting properties of chillies may not be fully understood, at least we have a good idea where to look to find the source of them. Cut a chilli open and you will see yellow placenta-like fronds that attach the seeds to the inside of the fruit. In most types of chilli, this is the location of the spice's secret weapon - capsaicin.

It is capsaicin that makes chillies hot. The heat is measured in Scoville heat units, which is the number of times a sample of dissolved dried chilli must be diluted by its own weight in sugar water before it loses its heat. For a green bell pepper this is zero. But habanero peppers have a Scoville value of between 100,000 and 350,000. For pure capsaicin the figure is 16 million.

While the Satanic-red horns of chillies seem to hint at their throat-scorching potential, extracted capsaicin is an odourless and colourless substance. Chilli-maniacs can buy phials of the stuff on the internet, though its use as a food additive is banned in the EU.

It's really not advisable to do anything at all with pure capsaicin

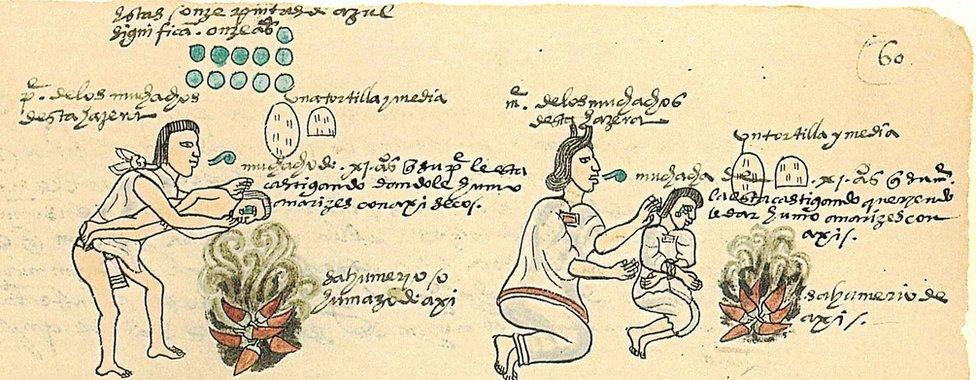

It is used in pepper spray, however. The use of chilli peppers as weapons dates back to pre-Columbian times, when, it's said, Mayans burned rows of them to create a stinging smokescreen. And in what may have been a pre-Columbian version of the naughty step, an ancient Aztec codex shows a parent propelling a teary-eyed infant near a pit of burning chillies.

The Codex Mendoza was created about 20 years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, and described aspects of Aztec daily life

However, the Aztec codices also tell us that they put chilli on their teeth to kill toothache pain, and the use of capsaicin as an analgesic also continues to this day.

Joshua Tewksbury, a natural historian at the University of Washington, thinks the burning sensation we experience when we come into contact with chillies is an evolutionary trick. "We're not actually being damaged by the capsaicin the way we would be if we were touching a stove, but our brain thinks we are," he says, adding that all mammals experience the same sensation but that birds do not. "They can eat chillies like popcorn and they don't feel the heat."

In this way, Tewksbury suggests, the plant evolved to repel animals that might crush its seeds with their molars, but not ones that would help disperse them.

Find out more

Listen to Lu Qi speaking to Health Check on the BBC World Service

Listen to Joshua Tewksbury speaking on The Why Factor: How Chillies Became Hot

More importantly for humans, chillies also evolved to repel microbes. This was of great value in the days before medicine and refrigeration, when, particularly in the tropics, people were vulnerable to bacteria that could harm them directly or cause their food to spoil. Chillies kill or inhibit 75% of such pathogens.

That may just explain the spice's world-conquering success. Just two or three years after Columbus brought capsicum seeds back from the New World in 1493, Portuguese merchants took the plants to Asia, where they would transform the cuisine.

It is sometimes said that people in hot countries use more chilli because it makes them sweat, which cools them down. But in 1998, researchers at Cornell University pointed out that the greater use of spices in countries such as India, Thailand and China was likely to be linked to their anti-microbial function. By studying recipe books from all over the world, the researchers found that spices including chilli were more likely to be used close to the equator, and were also used more in humid valleys than on high plateaux.

A picture from the 1830s of capsicum ustulatum, a kind of chilli

This correlation with climate, and the attendant risk of infectious disease, was greater than the link with the right growing conditions for the spices. In other words, humans in dangerous climates developed a taste for chilli which, as Joshua Tewksbury puts it, "probably saved them a lot of death".

We now know that chillies are also a good source of antioxidants. Forty-two grams of the spice would account for your recommended daily allowance of vitamin C, although admittedly that would make for a pretty strong curry. They are also rich in vitamin A, as well as minerals such as iron and potassium.

Capsaicin has even been touted as a potential weight-loss tool. Research conducted this year by the University of Wyoming on mice that had been fed a high-fat diet found that the molecule increased metabolic activity in the animals, causing them to burn more energy and preventing weight gain. In another study, published last month in Plos One, researchers at the University of Adelaide found that the receptors in the stomach that interact with capsaicin play a role in sensing when we are full. Previous studies on humans seem to back the idea that eating spicy food seems to curb our appetite.

Ixkimoll, a spicy casserole, is made by indigenous people in Mexico and served in clay casseroles at fairs

But what about heart disease and cancer? The recent study in China found a correlation between the consumption of spicy food and lower rates of death from those diseases - and laboratory research from the last 10 years suggests some possible reasons for that too.

In 2012, a team of nutritionists at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, working with hamsters, found that capsaicin helped break down so-called "bad" cholesterol which might have clogged up the animals' arteries, but it left alone the "good" cholesterol which helps remove it. There was a second benefit for cardiac health too - the capsaicin appeared to block the action of a gene that makes arteries contract, restricting blood flow.

Several studies have also indicated that capsaicin has powerful anti-cancer properties. It has been found to be helpful in fighting human prostate and lung cancer cells in mice, and there are also indications that it could be used as a treatment for colon cancer. It may also improve drug resistance for bile-duct cancer sufferers.

But before people make any radical changes to their diet, they are advised to wait for a clinical trial to be conducted using humans, not rodents.

"There are a lot of reports that say that capsaicin may be good for human health, especially with cancer," says Zigang Dong at the Hormel Institute of the University of Minnesota. "However, there are other reports that show totally the opposite result."

Green chilli bhajis for sale in Hyderabad, India

Dong is the co-author of a 2011 review, published in the journal Cancer Research, titled The Two Faces of Capsaicin, in which claims about the spice's benefits for health are laid alongside a long list of counter-claims, pointing to negative effects.

The report details six studies on rats and mice in which the animals developed signs of cancer in the stomach or liver after their diet was changed to include more capsaicin. Meanwhile, studies examining the effects of capsaicin on the human stomach have delivered wildly divergent results. While one showed visible gastric bleeding after consumption of red pepper, another showed no abnormalities, even when ground jalapeno peppers were placed directly in the stomach.

Korean kimchi: Chillies travelled to Asia from the Americas via Europe

"Probably it is harmful in the stomach or oesophagus because capsaicin itself can cause inflammation," says Dong. "And if anything can cause inflammation or so-called burning effect, it must cause some cell deaths and therefore the long-term chronic inflammation is maybe harmful."

Far from seeing the chilli's piquancy as an evolutionary "trick" that we are clever enough to see through, as Joshua Tewksbury does, he sees it as a hint to eat the food in moderation - a hint that many of us are ignoring.

Capsaicin - and the chilli pepper - remains enigmatic. But whether it is a friend or foe, we're exposing ourselves to it more and more. Between 1991 and 2011, global consumption of dry chillies increased by 2.5% per year, while our per capita intake increased by 130% in that time.

"There's a worldwide huge consumption of this spice, or vegetable, or whatever you want to call it," says Dong. "It's consumed everywhere in the world. Therefore its impact is huge for human health."

Capsaicin - a natural painkiller

Capsaicin creams and patches are available in chemists to ease pain. But it's only in the past 20 years that we have come to understand the contradiction of how something that causes pain can ease it too.

Capsaicin binds to the pain receptor TRPV1, which our brains also use to detect changes in temperature - that's why we think chillies are hot.

But after being over-stimulated the neurons stop responding, killing the pain. This process involves the release of endorphins, which can give us a "rush" not dissimilar from the feeling of having exercised well. This may explain why some people believe that hot food is addictive.

Lu Qi spoke to Health Check on the BBC World Service. Joshua Tewksbury spoke on The Why Factor: How Chillies Became Hot.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.