What's it like to answer angry tweets about trains?

- Published

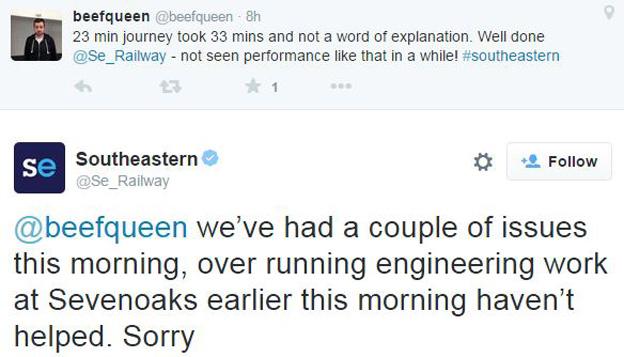

Every day people use social media to vent their spleen about delays, overcrowding and cancellations on the rail network. So who are the people responding to these irate comments?

There's a cow blocking the West Coast Mainline and hundreds of stranded travellers are complaining. A Liverpool footballer has his feet up on the chair opposite, causing ructions in first class.

A grieving relative wants to know how to get a coffin on board a Pendolino train, while another customer is stuck in the loo without any tissues.

These are just some of the issues raised with UK's train operators via Twitter or Facebook. Hundreds of thousands of people follow the companies' accounts, the writers usually known to the public only by their initials or first name.

Passengers suffering delays on train services are now quick to take to Twitter

Social media is becoming the default method of dealing with customers - perhaps because it is seen as softer and more approachable than conventional complaints departments, but also because of its sheer convenience as a means of sounding off.

A report by the information service Commute London found that in 2014 First Great Western received 265,201 tweets, closely followed by Virgin Trains on 257,254 and Greater Anglia on 241,038.

These figures are testament to the fact that train travel can be intensely frustrating, Across Great Britain, around one in 12 services are late, external and around one in 40 are cancelled. Inevitably, this can lead to some customers losing their temper and expressing themselves accordingly.

When Virgin Trains' Twitter service began in 2009, staff were instructed to ignore abusive comments, but there was a re-think about how to improve engagement. Now all but the worst receive a response.

Apologies are issued when services go wrong, along with advice on how to apply for refunds. Virgin's tweeters are encouraged to use humour to defuse tricky situations. Kayla Sheik, known to the firm's followers as "KS", describes herself as a "lover of fluffy cats and dogs", which she tries to show as often as possible because of their calming effect.

When a cow strayed onto a line recently, causing delays, followers were asked to tweet in bovine puns. On Mondays, the weekend's football results are discussed, while one member of Virgin's staff is a wrestling fan who likes to share his views on the sport.

"It's really tricky to get the tone right when responding," says social media consultant Gemma Went. "The whole basis of it is that people relate to other people. You don't want to feel like you're talking to a robot or being given brand messages. People like to talk to someone with an identity, but you don't do a series of humorous tweets if a whole bunch of people have just had their train cancelled."

"We try to get our personalities across," says Luke Ferris

The tweeters deal with customer queries and relay promotional material, but, unlike traditional corporate public relations staff, they have a degree of editorial independence.

"We try to get our personalities across," says Luke Ferris, head of the Twitter team for Virgin West Coast. "If there's not much happening and we're not getting much interaction, we try to encourage a conversation with people. When people are training we tell them the tone should be like a phone-in show."

Staff announce they're signing on and off, rather like one DJ handing over to the next, and conversations have a feel of local radio about them.

Southern Rail's tweeters recently became involved in a debate with a customer over the number of live chickens one could fit in a standard carriage. Northern Ireland Railways' "Jenny" has discussed her love of chocolate and coffee, while ScotRail's "Chloe" likes to retweet attractive landscape photographs taken by passengers.

Virgin's West Coast Mainline operation, based near Birmingham's Bullring shopping centre, has two people on Twitter duty at all times between 07:00 and 22:00, aiming to deal with each inquiry within five minutes. Staff deal with 700 queries and comments on an average day, rising to as many as 3,000 when there is major disruption on the network.

Ferris and his young team sit next to colleagues overseeing engineering issues, allowing a quick dissemination of information.

The approach is informed by that of the Dutch airline KLM, regarded in the transport industry as a trend-setter in its use of Twitter. Following the eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull in 2010, external, ash clouds grounded planes across western and northern Europe stopped for almost a week. Existing customer relations services struggled to cope.

So more than 100 KLM staff volunteered to help with a surge in Twitter inquiries, previously dealt with by a single employee. "From the ash cloud we learned that, as a company, we could tackle a crisis situation effectively using social media." Jochem van Drimmelen, head of social media at KLM, has said. "We also learned that the public really appreciated this form of communication."

While investing more in Twitter, the company decided to lighten the tone. This persists today, particularly in its use of photographs of crew enjoying themselves and cuddly toys on plane seats.

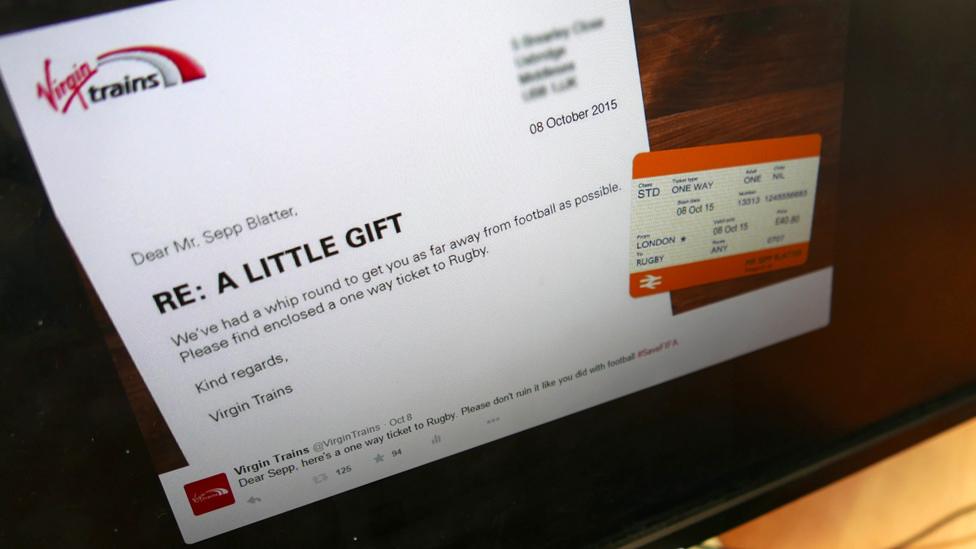

Companies, as a rule, avoid commenting on controversial topics, but Virgin purposefully took a position over the suspension of Fifa president Sepp Blatter earlier this month amid corruption allegations. It posted a letter, external offering him a "one-way ticket to Rugby", adding: "Please don't ruin it like you did with football." Is this a case of the company going beyond its remit?

"We've got involved in the conversation because that's what the audience wants to discuss," says Ferris. "It's encouraged by the bosses, something that sets us apart. It's engaging with the people who are on our trains."

In one recent exchange, a customer sent in a picture of Liverpool footballer Dejan Lovren sitting with his feet up on the seat opposite. The company tweeted, external, ordering him to desist or receive a "red card".

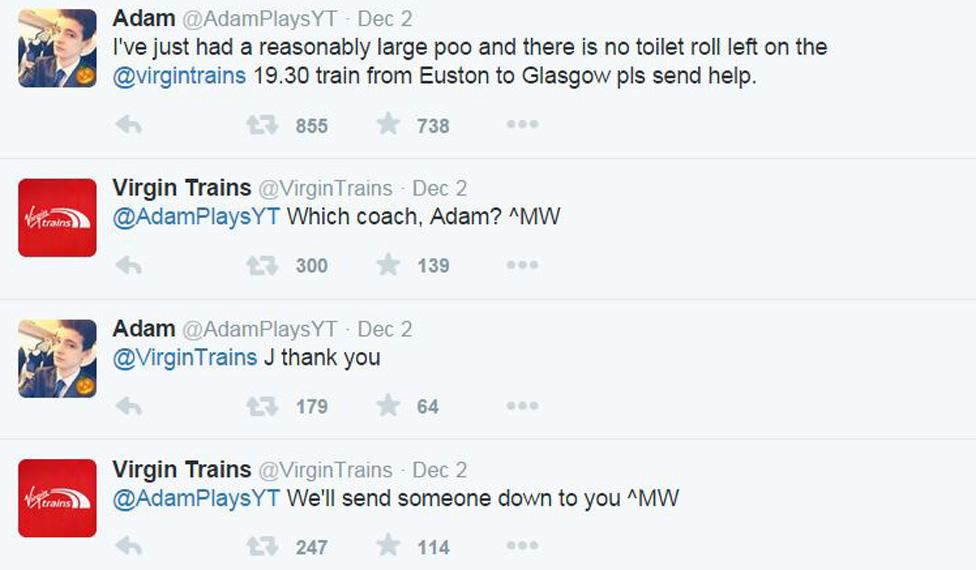

But the highest-profile instance of Twitter customer relations came in an incident in January dubbed "poogate", external. Teenager Adam Greenwood messaged Virgin to complain about a lack of tissues in a toilet he was using on board the train from London to Glasgow.

One of the company's tweeters, Mike Warrington, noticed and asked Greenwood which coach he was in. He replied and Warrington informed the train manager, who brought in fresh supplies.

The media picked up on the story, which was reported around the world. Virgin estimates that 300 million items were written or shared online about the episode. In China, the activities of Greenwood and Warrington provided the unlikely inspiration for an animated film.

"It surprised me when it became so massive," says Warrington. "It was crazy, but it was nice that people noticed what we do."

Mike Warrington, who came to a passenger's aid after spotting a tweet

Photographs, unless specified, by Phil Coomes

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.