Feeding the children of Boko Haram's victims

- Published

Behind the rusting walls of a Nigerian bakery, young boys forced out of their homes by Boko Haram, have found refuge. They are the sons of bakers killed or kidnapped by the insurgents and brought together by one man's kindness.

"Have you heard about the baker and the displaced people?"

I thought it was the start of a bad gag when my Nigerian friend asked me that. We were having a drink in a hotel in Maiduguri, Boko Haram's former stronghold.

Turns out, it wasn't a joke at all. He'd heard about a local bakery that had become a sort of refuge for people displaced by Boko Haram attacks.

Trying to find it was easier said than done. Maiduguri is a large city, the capital of Borno state, and I only had vague directions to the bakery.

When I got to where I thought it should be, I didn't see any buildings that looked like a bakery.

No sign, no telltale sacks of flour. Car fumes from the busy road overpowered any possible scent of baked bread.

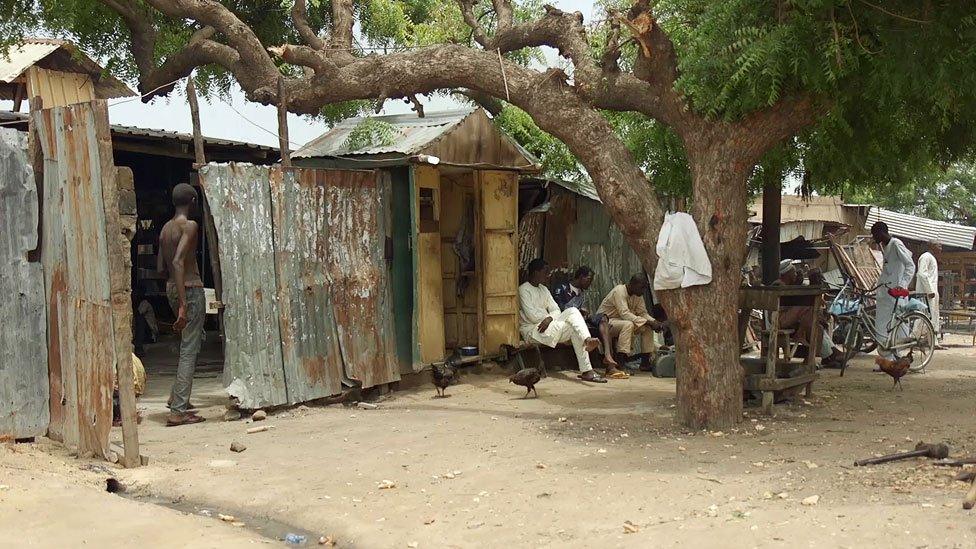

But then I saw it - a building with rusting, corrugated metal walls, and on top of the roof a brick chimney pot emitting a thin line of smoke. Something was cooking.

Inside, the baker came over, holding his fist against his chest in a traditional, polite greeting. He was tall, in his late 50s and was smartly dressed in a knee-length cotton shirt and loose trousers - it was Friday afternoon and he had just come from the mosque.

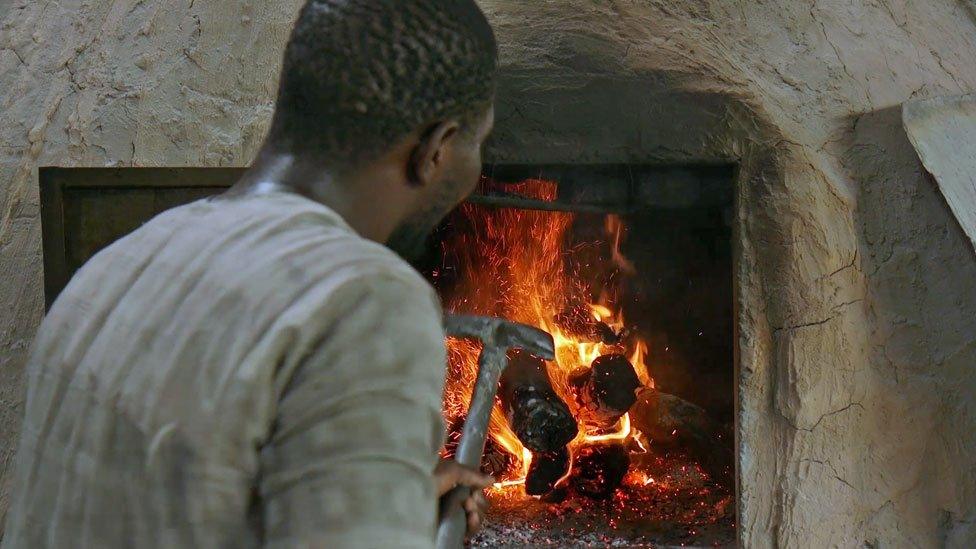

His bakery was equally tidy - made up of one large, main room with a cement floor and a brick oven in the corner. I was wrong - nothing was cooking there. The fire was going out. The day's baking was done. Piles of rectangular and round loaves of white bread were stacked on the wooden table, wrapped and ready for sale.

On the far side of the room, I saw about a dozen boys lolling on raffia floor mats. The youngest, I was told, was eight, the eldest 16. Some of the smaller ones giggled and returned my two-handed wave.

The baker and I sat on small wooden stools away from the oven. It was still giving out a good amount of heat. Via a translator, he explained that all these boys came here after Boko Haram attacked their homes. They are the sons of other bakers, from villages outside Maiduguri. Their fathers were among the thousands who had been killed or kidnapped by the insurgents.

The boys clear up after a day's baking

The baker felt responsible for the welfare of other bakers and their extended families. They started arriving in 2012 - just a few people at first but last year Boko Haram intensified attacks in and around Maiduguri. More people started to arrive looking for shelter, food, water and money. He said he had helped find homes for almost 300 people, most of them women and children.

Some live in shelters in his garden, others, like these boys, stay in the bakery. He gets no support from local government. What he does to help, he does alone.

More than two million Nigerians have been displaced during four years of fighting. Fewer than 10% of them live in official government camps. Most rely on friends, family or virtual strangers like this baker.

But his resources are limited - his gently rusting surroundings attest to that. He can't offer these growing boys much more than a roof over their heads and endless bread to eat.

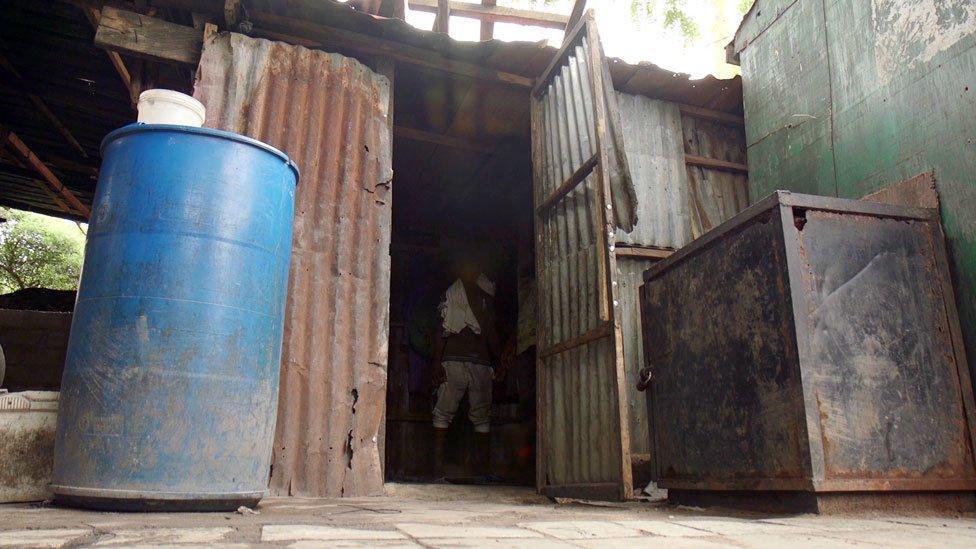

He pointed to a small shack in the corner by the entrance. I thought it was a cupboard but it's where these 14 boys sleep. It was no bigger than a small garden shed. A few clothes hung on nails in the walls. In one corner, someone had neatly rolled up the sleeping mats.

The small shack where the boys sleep

"Do you get into fights?" I asked one 15-year-old boy who has lived there for two years. He laughed and nodded but said he always tried to get in early to secure his favourite sleeping spot, in the corner, by the room's only window.

That's where he keeps his little bundle of things, including an English vocabulary book. It's just a couple of tired-looking pieces of paper stapled together. He practised some words on me, numbers mostly, hellos and goodbyes.

I asked about school. He shrugged and told me he hasn't been since arriving here. He wants to go back though, once he gets home. He wants to study and become what he calls "a big government man". For now those dreams are being kept alive in this shack, with this tiny bundle of English words and the generosity of a baker.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Thursdays at 11:00 and Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.