The billion-dollar ex-council flat

- Published

A bizarre trail leads from an impoverished former Soviet republic to the palm-fringed shores of the Indian Ocean and beyond, via a Scottish ex-council flat - the trail of $1bn stolen from Moldova, Europe's poorest country. For the first time, the flat's owner has shed further light on the mystery.

A gritty Scottish housing estate is not the obvious place to search for $1bn that's gone missing from a small country at the other end of Europe.

But a modest ground floor two-bedroom ex-council flat in Pilton, north Edinburgh, is home to a mysterious firm with the right to collect that vast sum, allegedly stolen from the former Soviet republic of Moldova.

The Pilton flat in question is home to an astonishing 530 firms registered at the address.

Welcome to the bizarre world of shell companies, which can be used to conceal the real owners of assets - and the agents who create them. Donald Toon of the National Crime Agency - the man effectively in charge of the UK's fight against dirty money - says he's "very worried" about the role played by the agents.

Pilton is perhaps better known for its appearance in Trainspotting - Irvine Welsh's novel, later made into a hit film, about poverty, crime and heroin addiction - than as a surreal portal to a tropical paradise in the Indian Ocean.

But the BBC has discovered it has become just that.

One of the companies registered at the address is Fortuna United LP, the UK partnership named in a leaked report by Moldova's central bank as the firm with the rights to the billion dollars which disappeared last year from three of the country's main banks.

The loss of the money - equivalent to an eighth of Moldova's entire GDP - has thrown the country into economic and political chaos.

Thousands of protestors gather every weekend in the capital Chisinau to demand the return of the cash and the punishment of those guilty of the alleged fraud.

Fortuna United is named in the leaked report, by the New York-based corporate investigative agency Kroll, as the firm that is ultimately owed the entire proceeds of the Moldovan fraud.

But Fortuna United is obviously not doing any business in the flat in Pilton.

The only firm that is appears to be Royston Business Consultancy, a company formation agent or corporate services provider - that is, a company that sets up other companies - which registered Fortuna United and the firms officially housed there.

Royston Business Consultancy is run by a 36-year-old Lithuanian, Viktorija Zirnelyte, who owns the flat, and her business partner, fellow Lithuanian Remigijus Mikalauskas.

Her office is a homely front room with a row of ring-binders on a shelf among photos and ornaments, looking out on a privet hedge. She trained as an accountant, moved to Britain in 2004 and worked a series of odd jobs before starting this factory churning out companies.

She says she and Mikalauskas not only set up Fortuna United, they are directors of the two firms behind it - even though those firms are themselves officially based thousands of miles away in the Seychelles Islands.

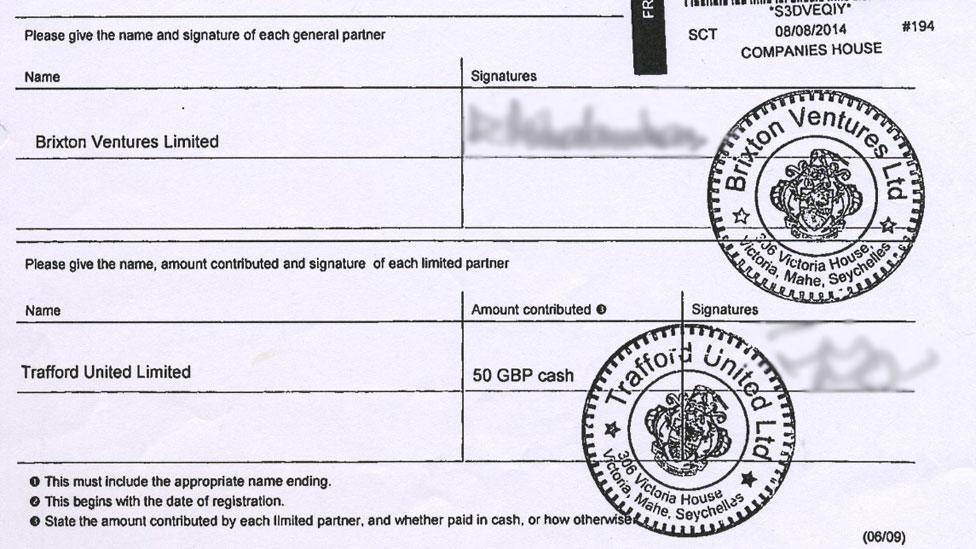

Fortuna United is a limited partnership made up of two Seychelles companies - Brixton Ventures Ltd, whose director is Mikalauskas, and Trafford United Ltd, whose director is Zirnelyte.

But they have never been to the Seychelles, and official Seychelles ink stamps used to register Fortuna United at Companies House in the UK were not sent from the islands.

Zirnelyte says suitable stamps can be bought on the online auction site eBay.

There are estimated to be about 2,600 corporate service providers like Zirnelyte and Mikalauskas's firm in the UK, in addition to some legal and accountancy firms who offer the same services.

The UK is one of the easiest countries in the world to set up a company in, and some agents offer to do it in an hour, for as little as £25.

Agents are required under the UK's money-laundering regulations to satisfy themselves that their clients aren't involved in illicit activities, and to know the "beneficial owner" of any firms they set up - in other words, who really controls the assets.

Zirnelyte says she knows who ultimately controlled Fortuna United, though she cannot reveal their identity.

She says her firm did not ask "details of the business" of the companies they set up. She says that is the job of "intermediary agents" - other corporate service providers she declined to name, mostly in eastern Europe, who pass customers on to her.

What are 'shell companies'?

They are firms that only really exist on paper, used to channel funds or assets without actually having any employees or carrying out meaningful business

Agents known as corporate service providers often set up shell companies for a fee, sometimes providing them with a postal address and directors

The corporate service providers must know the identity of the "beneficial owner" behind any shell companies they set up and have to satisfy themselves that their clients aren't involved in illicit activities

She says she and Mikalauskas were just "nominee directors". She adds: "Nominee director is just an official representative for the authorities, and he is not involved in anything."

But barrister Jonathan Fisher, QC, one of Britain's leading experts in this area of law, says that legally, nominees would be as responsible as any other director for any wrongdoing.

"All that 'nominee director' means is that the person holding the position has been nominated to hold it on behalf of somebody else," he says. A director "has to understand what the company is doing, he has to be involved in the management of the company".

Zirnelyte adds: "I don't have anything to worry about. I didn't commit fraud myself or my partner didn't do it. We comply with all the regulations."

Toon, head of the economic crime command at the National Crime Agency, will not comment specifically about companies allegedly involved in the Moldova case.

But he says: "Trust and company service providers, company formation agents, those professions cause us real concern. The skills in those areas are essential to the type of money laundering we're talking about."

Donald Toon, head of the economic crime command at the National Crime Agency

Toon says he is particularly worried that corporate service providers rarely alert the authorities to possible suspicious activity by clients, as they and others in the financial sector such as banks, lawyers and estate agents, are required to do.

Of more than 350,000 Suspicious Activity Reports to the UK financial intelligence unit last year, just 177, or 0.05%, came from company service providers.

Britain is now one of the nations leading a global fight for more company transparency. Prime Minister David Cameron told a conference in Singapore in July: "We are one of the most open and welcoming economies anywhere in the world and I want Britain to be that country. But I want to ensure that all this money is clean money. There is no place for dirty money in Britain."

A new law that takes effect next year will require UK firms to disclose their beneficial owners. The UK will be the first country in the world to adopt such legislation.

But campaigners for greater transparency are concerned that no-one will check the accuracy of information firms give.

"There are going to be problems with the data. People will lie," said Robert Palmer of the international anti-corruption group, Global Witness. "In the UK, about 75% of companies are created by a company service provider or a lawyer. So it's really important those professionals are doing proper checks on their clients."

The BBC has found that corporate service providers abroad have been advertising particular UK company vehicles, such as Scottish limited partnerships (SLPs), as ideal for clients seeking confidentiality.

Of the 48 UK firms said to be involved in the Moldovan fraud, 28 - including Fortuna United - are SLPs.

Research by the financial journalists Richard Smith, UK editor of the Naked Capitalism blog, external, and Ian Fraser shows the number of Scottish partnerships has suddenly jumped in recent years. Of the 6,000 formed in the past 18 months, 90% of them have corporate partners based in overseas tax havens.

"With the abuse of limited partnerships and limited liability partnerships - the opportunities they provide in terms of opacity of ownership, we are also a secrecy jurisdiction," says Fraser.

"Britain is just like the Maldives, the Marshall Islands, the Cayman Islands - the whole archipelago of tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions around the world."

Protesters in Chisinau, Moldova

Moldova's lost billion

The state was forced to bail three banks out after $1bn (£655m) vanished from their coffers. The missing money caused a rapid depreciation of the national currency, the leu, and a decline in living standards. Protesters have demanded the resignation of President Nicolae Timofti and other officials, including the governor of the national bank, and early parliamentary elections.

The great Moldovan bank robbery

Listen to the File on 4 report Dirty Money UK on the BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.