The disaster that liberated me

- Published

When the Kashmir earthquake struck in October 2005, Tabinda Kokab was a teacher in a remote village close to the epicentre. She recalls the day that changed her life, and how it forced her to throw off the expectations that Pakistani society had placed on her as a woman.

I sometimes think there is another Tabinda Kokab. She is a housewife with four or five children. She lives in someone else's home, which she keeps clean and tidy. She is demure and obedient and doesn't make her own decisions about anything. This imaginary woman is very different from me, and yet we share the same childhood. On 8 October, 2005 our lives diverged forever.

It was a quiet day at the start of the holy month of Ramadan. People were taking it easy because of the fast, and a few children who were off school that day were playing cricket in the street.

I was 22 and living with my parents in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan-administered Kashmir. I worked as a primary school teacher in the mountain village of Karka, an hour's bus ride away. It was my second year in the job, but I wasn't starting out on a long career. My salary was little more than pocket money, and the expectation was that one day I would get married and quit my job.

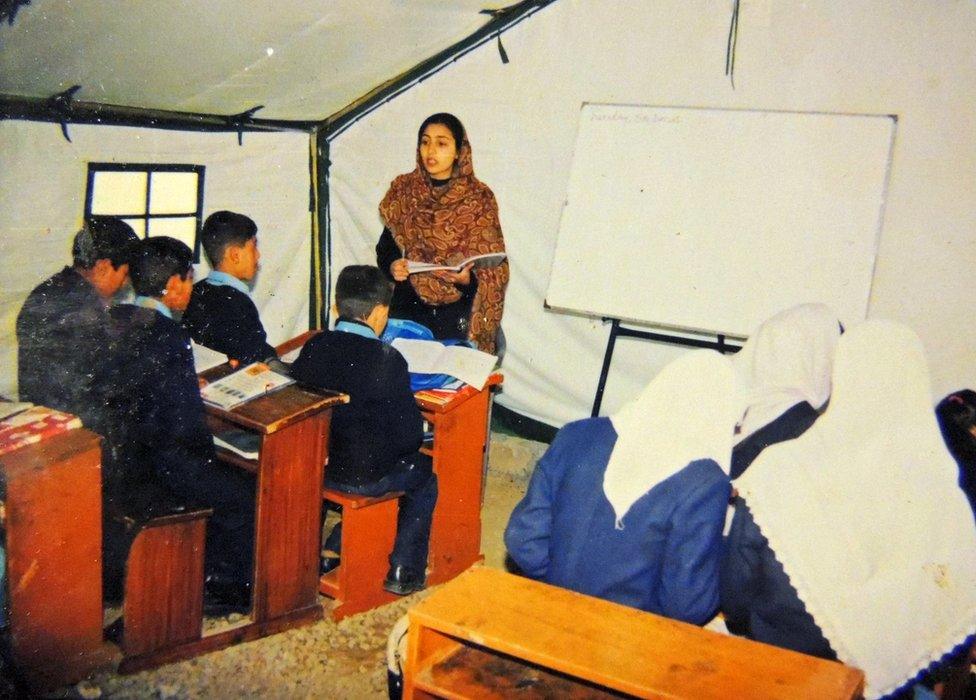

Tabinda teaching at the school in 2005

It was the only school for miles around that taught in English. The children came from tiny villages and were so poor they could barely afford their uniforms, but my colleagues and I were trying to make them look like and speak like children in the cities and to give them the same opportunities.

The first period of the day was about to end, and I was just flicking through the children's books when there was a tremendous blast. It lasted perhaps four or five seconds.

I knew I had to get the children out of the classroom, but when I stood up the wall in front of me began to fall apart. I was in shock. I tried to walk towards the door, but it kept moving - right, then left.

Then the children gathered around me, grabbed me, and clambered over one another to hold on to me. While I was trying to move towards the door carrying 10 or 12 children the building collapsed on top of us all.

I felt nothing, no pain.

I just lay there, thinking, "OK, this is it. I am going to die. I just have to wait for a while. But for how long?"

It was a newly-built two-storey concrete building, and my classroom was on the ground floor. But something told me to look up, and I found I could see the sky, and I was even able to pull myself free from the rubble. My feet were bleeding. I could see some of the children around me, half in the debris, half out. I tried to pull them free too.

I thought, "Where are all the other children? Where are all the teachers?" There were only a couple of teachers about, and I couldn't see many of the 110 children who attended the school.

People were crying, shouting and trying to understand what was happening. No-one thought about an earthquake. We thought perhaps a huge bomb had exploded in a nearby town. The aftershocks continued for another hour before the dust settled and we were able to see the mountains on the other side of the river. And at that point we saw that the roads, the houses, the village had all disappeared. Huge landslides had destroyed everything.

I remember one of the children - a seven or eight-year-old girl - brought my purse to me, and said, "Teacher, here is your purse. You might have something important in your purse."

And I was just thinking about the trapped children, and I was shouting, "Someone please come! Please come, my children are inside!"

A man, who was running along the river, perhaps to go home and check on his own family, stopped and looked at me. He said, "Who are you?" I said, "I am a teacher in this school, and the children are inside."

He said, "Are they your children?" I said, "Yes, all 110 of them are my children."

He looked at me a long time and then carried on his way. What could he have done anyway?

After about five hours, a man arrived from Muzaffarabad and we asked him, "Where is the government? Where is the army? They should come and help us."

And he said, "What are you talking about? Muzaffarabad is destroyed too. There is nothing left - hospitals, schools, government buildings are all destroyed. No-one can help us."

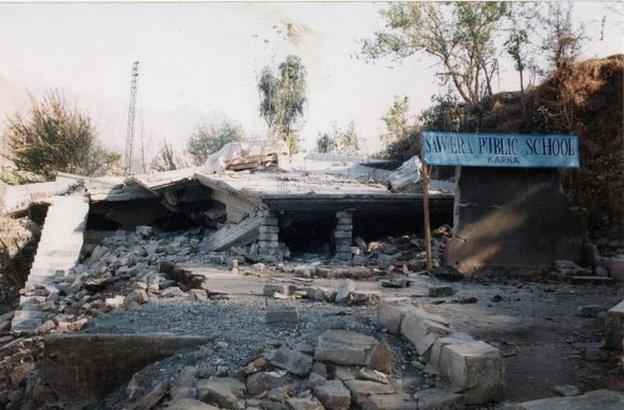

The school in Karka after the earthquake

The faces of my family and friends in Muzaffarabad flooded my mind. I thought about the city, with its tall buildings, and I thought about my own home there. Could it possibly have withstood this earthquake?

I had one brother and five sisters. For five days I prayed, "Please God, please God, let some of them be alive. I cannot be alone in this world. Please save some of them for me, so that I have someone to live with."

I was staying in a tent with a local family that I had met a few times in the past. Some of the surviving children from the school were in our encampment too. My left foot had been crushed and it hurt to put weight on it, but it was not a serious injury.

Then a man arrived from Muzaffarabad who was like my angel sent from heaven. He knew my family and he told me he had seen them alive. By this time my foot had healed somewhat, and, two days later, I joined a group that walked the 10 miles (16 km) back with him to Muzaffarabad, across the mountains.

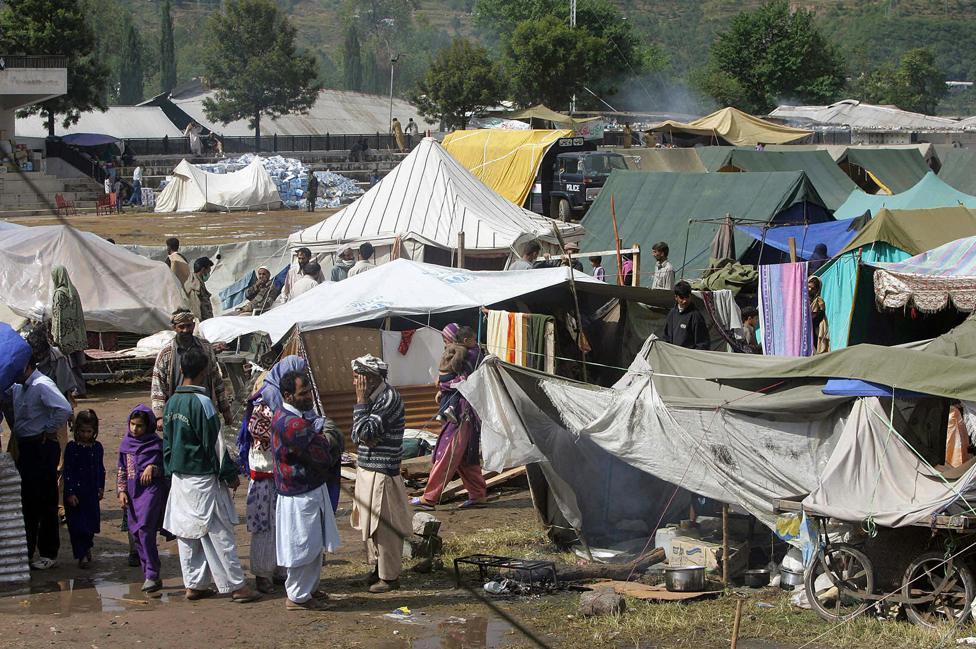

The roads and transport links in the surrounding area were destroyed

For speed, we decided to follow the original line of the road, which in places had been ripped away from the mountain. Other villagers took higher paths around the valleys, but that meant a journey of several days. Instead, it took us nine hours and it was the most horrible journey of my life.

On the sections that had been affected by landslides, scree and mud led straight down to the river below. With every footfall, more rocks tumbled down, so that it was impossible to follow in the steps of the person in front. I hobbled and limped along, slipping a great deal, but somehow or other I made it to Muzaffarabad.

I was expecting to find a scene of chaos and mourning but the city was so quiet. Almost everyone had left.

You could see into people's houses because walls were missing. But instead of families, there were just smashed plates and clothes tumbling out of cupboards. Blood was spattered across the road.

I stopped at a friend's house and it was there that I learned - and she had to tell me several times before I really understood what she was saying - that my brother was dead. I ran all the way to my father's house. When he saw me he came out and held me in his arms. "Stop crying," he said. "You only lost your brother, but some families have lost three or four people."

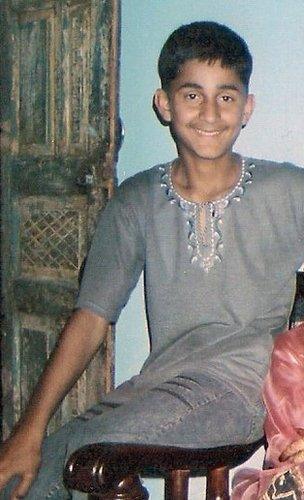

My brother, Hammad Ali, three months before the earthquake

I learned that those were the first words my father had spoken in five days. After he had buried his 15-year-old son next to the cricket pitch - my brother's favourite place in the city - my father's voice disappeared and was replaced by a whisper, a croak.

In the coming months, I often thought that it would have been better if God had taken me or one of my sisters rather than my kind, generous brother Hammad Ali.

The pain of loss would have been equal, but you have to understand that in our society the dreams of parents and sisters are lived through their sons. We thought he would grow up to take responsibility for the family, to be our protector and shield. My sisters and I lost our shield that day, and we realised that one of us would have to take over.

I was the oldest unmarried girl in the family, and the most highly educated. I was also the most confident - my sisters said, "It has to be you, Tabinda. You can speak to people."

This wasn't a comment on my ability to connect with strangers - they meant it quite literally. They were far too shy to address a word to anyone outside the immediate household, even to my cousins. If someone asked them a question, they would nod or shake their heads.

Looking back, I was also very shy. I remember being terrified whenever I heard my name on a stranger's lips. I would think, "How does that person know me?" When we were growing up, we girls never went shopping or to the markets, we just went to school and then straight back home. Our lives were very limited.

And yet I had graduated high school and got a job as a teacher. My confidence and education definitely impressed the young girls I knew. I used to overhear them taking turns to pretend to be me in their games. "No, it's my turn to be Tabinda," I would hear them say. "You can be someone else."

In this way, I had become conscious I was setting an example, so I already had a sense of responsibility. And now that my brother was gone and my father was retired I decided that yes, I would protect my family. I would be a son to my parents and a brother to my sisters.

So instead of getting a husband I would get a job - one that paid well. On 4 January 2006, I took up a post with an NGO working in disaster relief, replacing my teacher's salary of 2,200 rupees a month (in 2006, $37 or £21) with one of 800 rupees a day ($13 or £8).

But the work was hard. I had to do a survey of casualties and deaths caused by the earthquake, which meant going to the temporary relief camps and asking survivors, "How many people were injured in your family? How many died? How many are still missing?" Every day brought a different family for me to cry with.

Find out more

Listen to Tabinda Kokab speaking to The Fifth Floor on the BBC World Service

Get the Fifth Floor podcast to hear more stories behind the stories on the BBC World Service

In a way it was good, because it put my own loss into perspective, but this daily body-count was too much for me. So I joined another organisation that was running an aid camp for displaced people. Slowly I began to feel better, more confident and positive.

I worked for aid agencies for three years, but on 9 June 2007, I got the chance to fulfil a childhood dream when I started an internship as a journalist with the BBC's Urdu language service in Islamabad.

"Who helped you?" my editor asked me after I put my first news story together. "No-one," I said.

I had picked up some journalistic skills while I was collecting stories from displaced people in Kashmir. But more than that, ever since childhood, my sisters and I had been avid readers of newspapers. After all, we never went out, so the newspaper was our way of knowing the world. And I found that I had a very good technical understanding of what constituted a news story, how to order the ideas and compose the headline.

By chance, five months after I started at the BBC, President Musharraf declared a state of emergency. It was part of a big face-off with Pakistan's judiciary. All the judges were placed under house arrest and for three months domestic news outlets were shut down. Only the BBC carried on. Suddenly we interns were not cobbling together radio bulletins but providing live coverage of the protests taking place outside the judges' houses.

Bit by bit I became more confident and left behind that shy girl, the village teacher.

In spite of everything that the earthquake took from me, it gave me the courage to build a different life.

And I am not alone. This week, I went back to Muzaffarabad and interviewed several other women whose lives changed unexpectedly after the disaster.

Women like Samiya Sajid. In 2005, her husband was being treated for a brain tumour but after the earthquake he couldn't get the treatment he needed and he died. Samiya decided to take over his cable-laying business, and of course there was no shortage of work after the earthquake. After she had made a success of this, she started a local TV news channel, and now she is a politician too.

She is such a strong lady. While I was interviewing her, I saw at times that she was crying, but you would never know it if you listen back to the tape. She is that composed, that the strain does not show at all.

"I never listen to anyone," she told me. "Because I have to live a graceful life. I have to give my children a safe future, so I will do my work regardless of what people say."

Then there is Shajida Tanveer, whose husband left for work that October morning in 2005 and never came home. Despite being pregnant at the time, Shajida searched the city for his body in vain, her toddler in tow.

Her husband was a government worker, and after he went missing she was given a job in his office. Eventually, she bought land and built a new house, picking out the materials herself at the builder's merchant. I asked if she had ever thought about marrying again. "No," she said, "my children are my everything."

Men praying at Muzaffarabad's Jama Haman Wali mosque three weeks after the earthquake

But I don't want to overstate the effect of the earthquake on women's position in Muzaffarabad. Most of the woman I knew who - like me - were working for NGOs after the disaster are now housewives. OK, being married and taking care of your family is good. But I want to ask these women, What about you? Where is your career? Where is your personality?

Their husbands won't let them work. And although right now my nieces look up to me and say they want to be journalists too, I don't know if that will happen, because in our society, the view prevails that good girls stay at home. Women like me, who go out and work, and don't feel afraid to address themselves to anyone, are judged in Pakistan. We have, people say, failings in our "character".

It will take more than an earthquake to change that mind-set - it will take a whole generation.

My father has never opposed my pursuit of a career though and I married a man who fully supports what I do. Six years ago, I became pregnant. It is God's will whether you have a boy or a girl, but I confess I was secretly praying for a boy. God granted my wish and I named him Hammad Ali.

And when he was five months old I took him to my parents' house and gave him to my mother and father. I live in Islamabad but he lives in the family home in Muzaffarabad. My brother is no longer with us, but his name lives on in that house - and because my son is very naughty, it rings out from morning until evening.

We have now refurbished the family home, though it took us a long time because we decided to pay for it all ourselves. The government in Pakistan announced a compensation package of 25,000 rupees ($240 or £160) for an injury and 100,000 rupees ($960 or £630) for a death. But neither my father nor I wanted that money. We couldn't help seeing it as a sort of substitute for Hammad. And by paying for the building work itself, we have built a house that not only keeps us safe but keeps our dignity safe too.

There is now a house where the school in Karka once stood

I go there all the time, but on Monday I went back to Karka, the village where I worked as a teacher, for the first time in 10 years. But I might add that in my dreams, I have often returned to Karka and the person I was in 2005.

What was a little village is now a town. All the little paths are now wide roads and everything is clean and new. The pain has been wiped away. The areas affected by landslides are overgrown with grass and trees, and in vain I searched for the patch of ground where I camped out in the week following the earthquake. The area is covered with concrete houses, paid for with compensation money.

Everyone got the same amount, regardless of whether their home had been a mud hut or a large concrete house, so while proper toilets used to be a rarity in the village, now almost every home has one.

My school was rebuilt in a different location and the original building - what was left of it - was renovated and reconfigured as a private house.

But the gate is the same, and the same path winds up from the road. And as I walked up that path, I didn't see the new home but the old, two-storey concrete school.

"I was a teacher here 10 years ago," I told the family in the house. They remembered me and talked with me, but as we spoke my mind drifted over the memories dislodged by the old building. I was overwhelmed with a feeling that while everyone in Karka had moved on, part of me was still stuck in 2005.

I learned that 16 children had died in the earthquake that day. As we talked, I tried - and failed - to keep a lid on my feelings.

I said, "There was a girl who brought me my purse - who was she?" and a woman who was sitting there said, "She was my daughter, and she is at home today."

Before long, an 18 year-old woman, so lovely and grown-up, approached our group. Overflowing with excitement, she grabbed hold of my hand, saying, "Teacher I remember you, and I think about you often."

It was so lovely to see her. It emerged that she had left school when she was about 12, and I told her to go back to her studies.

She said, "OK, I will, because you gave me the order and I will not refuse you."

The 2005 earthquake

The epicentre of the 7.6 magnitude earthquake was about 80km (50 miles) north-east of the Pakistani capital Islamabad

It was felt across South Asia, from Afghanistan to western Bangladesh.

It was widely reported that 75,000 people died and a further 70,000 were injured although Pakistani government figures were higher

Up to three million people were left homeless

Tabinda Kokab spoke to The Fifth Floor on the BBC World Service. Production by William Kremer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.