The man who can only say yes and no

- Published

It's common to have communication problems after a severe stroke. But Graham Pawley is an unusual case in that he can understand everything but say virtually nothing back. He has to get by with "yes" and "no".

Communicating with Graham is a bit like playing that game where you have to keep asking yes and no questions until someone gets the right answer.

I'm sitting on the sofa in Graham's flat looking at his medical report. He is trying to tell me to read it out to him.

It's not strictly true that Graham can only say "yes" and "no". He can say "and", "no" and "mmm", which means yes, and he also makes an "urr" sound. When he says "and urr…" it means he has something else to say and wants you guess what it is.

"And urr…" he says while I read the report.

"Yeah, it's really interesting for me to see this," I say.

"No.''

"Sorry, are you sure it's okay for me to look at it?"

"Mmm, mmm. And urr…"

"You want to have a look at it?"

"No," he waves his left hand in an indecipherable way.

"I can keep it?"

"No," more gesticulating. Paul Webley, Graham's "befriender", starts guessing too. "It's good? He's the first person you've let read it?" says Webley.

"No, no, no," says Graham.

This carries on for a minute or two. Apart from a few movements Pawley can't really use his hands to express himself either. "It's helpful? I'm helping?" I ask.

"Mmm. And urr…"

"Oh, you want him to read it to you?" says Paul.

"Mmm, mmm," says Graham.

"You see, we always get there in the end," says Paul and smiles.

In July 2013 Graham had a severe stroke that has left him almost unable to express himself. He can't read properly or write but he is able to understand everything said to him. He can't move his right arm and has limited movement in his right leg, both of which cause him pain.

A stroke happens when the blood supply to part of the brain is cut off - often by a clot blocking a blood vessel. "The repercussions of a stroke can impact your brain in a huge spectrum of ways. Almost all of which are life altering," says Cate Burke, assistant director of education and training at Stroke Association.

"Graham's condition is called aphasia," says Prof Tony Rudd, NHS England's national clinical director for stroke. "It's quite unusual to have severe problems in communicating and not be affected in terms of your understanding."

But it can happen. "Although the section of your brain that controls communication is closely interconnected to the bit of your brain that controls understanding, the two are separate," Rudd explains.

"Aphasia can mean that you just have trouble finding the right words. But it can also be worse, in which case the patient would have absolutely no understanding of what's been said to them as well as not being able to express anything."

Aphasia and Stroke statistics

About 33% of people who have a stroke are affected by aphasia

Stroke occurs approximately 152,000 times a year in the UK - that's one every 3 minutes 27 seconds

First-time incidence of stroke occurs almost 17 million times a year worldwide - one every two seconds

There are around 1.2 million stroke survivors in the UK

Stroke is the largest cause of complex disability - half of all stroke survivors have a disability

Over a third of stroke survivors in the UK are dependent on others, of those one in five are cared for by family and/or friends

Source: Stroke Association, external

It seems Graham's case is severe but not unheard of. He can't write, or read more than the odd word or two, but he can follow television and films. He can use a phone but he can't text any more than a letter or two.

Always impeccably turned out in a tailored shirt and thin tie, Graham, who is 56, lives in extra-care sheltered housing near King's Cross in London. The flat is on the fourth floor of a brand new tower block that has 24-hour care. Almost all of the wall space in the flat is covered with large bright oil paintings.

A self portrait in a section in one of Graham Pawley's paintings

"He painted all of those, he loves Caravaggio," says Paul. "That's him in that one." The profile of a man with short hair and sporting a beard can be seen in the top right looking over and past the other figures in the painting.

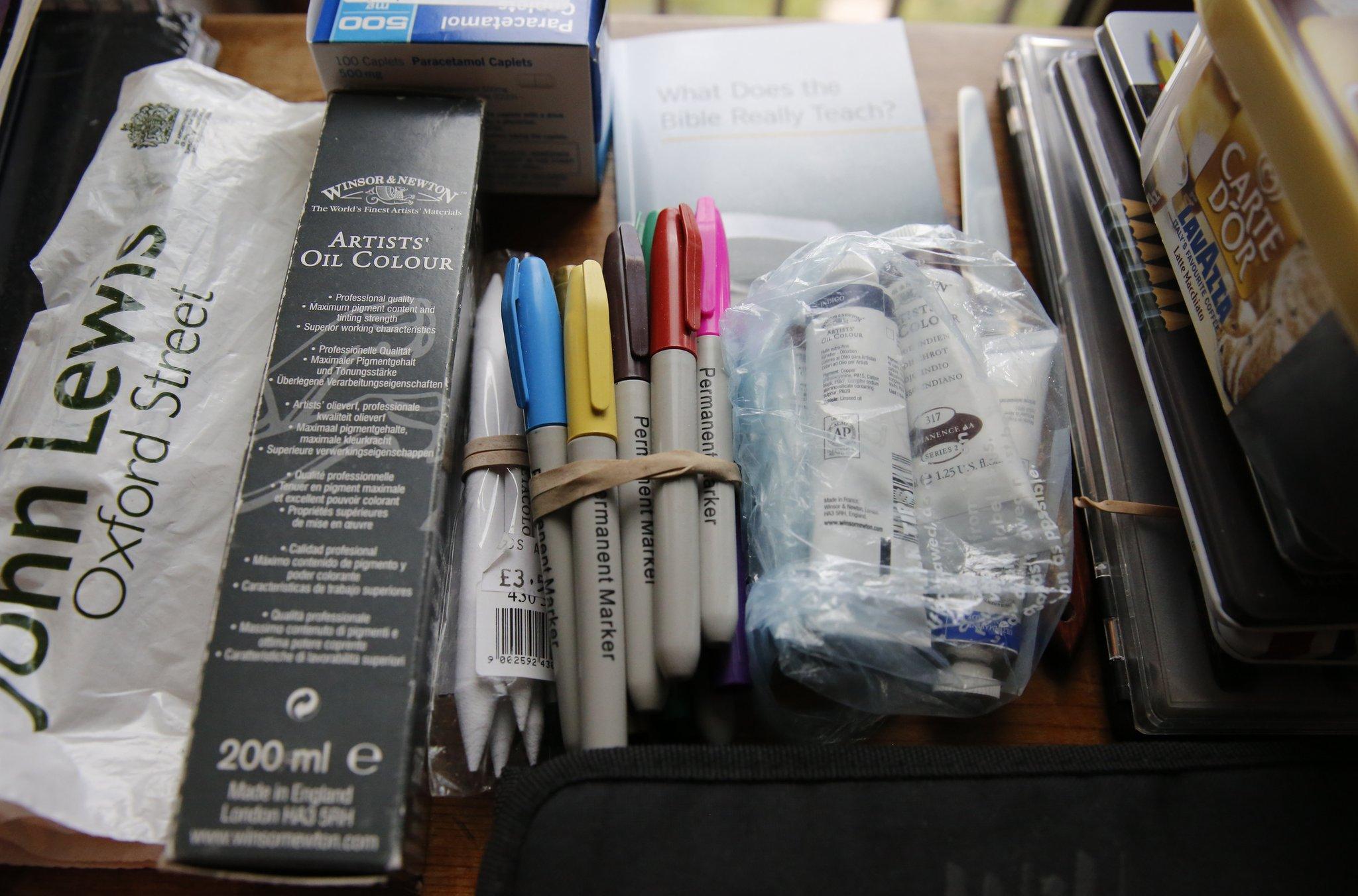

The agony of the change that has happened to Graham becomes apparent as you get to know him. The stroke has put an end to doing the things that defined him. "He used to paint, draw, busk and make his own clothes. He can't do any of that now," says Paul. Neat collections of felt-tips, crayons and tubes of paint lie unused on a dining table.

Graham has the motor skills in his left hand to tap and swipe at his iPad and load his cigarette-rolling machine but is unable to make complex movements. One of his paintings hangs damaged on the wall. He is no longer able to repair it.

It's clear from his appearance, his cleanliness and the order in his flat, that Graham is interested in detail. Inside a black plastic file, kept in a bedroom cupboard, is a series of chronologically ordered employee reference letters.

The thin envelopes are held together by an elastic band doubled around them. One by one Graham holds them out. He was a mechanical engineer. The letters tell a story of his career moving from sewing machine construction to developing components for aircraft.

There are videos on YouTube, external uploaded in 2008 of Graham playing the harmonica. He was watching one of them on an iPad when Paul came to visit. Graham used to busk in Camden in his spare time. His harmonica is kept in the cardboard box that it came in, placed in a drawer under the TV. Framed family photographs line the surfaces in the living room and bedroom. Many of the images are of his son, Alex, who died aged nine from a condition that he was born with.

Bright waistcoats that Graham tailored himself hang in colour order on a rail in the bedroom. Graham holds one up by the hanger. "Alex", reads the hand-stitched label on the inside. "Oh, because that was the name of your son?" says Paul.

Paul Webley is the befriending coordinator at Opening Doors, a support charity that helps LGBT people who are over 50. "Graham was referred to me by Age UK Camden in January. They have contact with the people who work in the extra care accommodation," says Paul. "Instead of finding him a befriender, I took him on myself."

Paul Webley (left) and Graham Pawley first met last January

Paul sees Graham every other Saturday. "It was an unusual case and he needed a gay mate," Paul says. "I walked in here and thought, 'How the hell are we going to do this?' Two hours later it felt like we'd been properly chatting for hours."

The pair knock along together, smoke the odd cigarette and laugh at each other. For someone who can't ask a question or crack a joke, Graham is surprisingly good company.

A man-made swimming lake is part of a new development below Graham's flat

Apart from Paul, Graham doesn't have many friends who come to visit him. He broke up with his wife 12 years ago, came out as gay and moved down from High Wycombe to live in Camden, north London.

He doesn't often see one of his grown-up daughters, as she has been ill in hospital, but his other daughter visits every couple of weeks. Graham rarely sees his ex-wife but says that they are now on good terms. His sister comes to see him every so often. Graham had another brother, says Paul, but he died some years ago.

Graham wears a black hat with a series of small feathers tucked in the side. It covers a large circular scar left by surgery after the stroke.

"The brain is plastic and although the bits of the brain that Graham used to use for speech are dead the other bits can be trained over time to do their job," says Burke.

"I don't like to say that people will never recover but it's unlikely that he will make a full recovery," Rudd says. "Speech therapy and talking to people will help and improve Graham's level of communication."

Graham breaks down in tears when asked about how he feels about what has happened to him.

To see this enormously positive man speechlessly cry, as he sits by the window in his flat, gives a brief glimpse into the depth of the impact that the stroke has had on his life. Graham's tears dry and he takes his time to recomposes himself. Perhaps incredibly, he looks happy.

Later in a vintage clothes market Graham tries on a jacket that is part of a suit. He is standing up from his mobility chair and looking in a mirror that Paul's holding up for him. The stall owner is laughing and a couple of other customers tell him that the jacket suits him. He manages to haggle the owner down to £35, minus the trousers, which he rejects due to a stain on the inside leg.

Football managers often talk about their best players having character. They are referring to work ethic, pain threshold, and a passion for the game. Like so many people who have had what they know removed from their lives, Graham's stroke has revealed his character, the passion he has for life. The pleasure that he draws from his ability to charm and disarm people is infectious and makes his acquaintances forget his limitations.

"Do you see what I mean?" says Paul as we walk away. "It's like that with everyone he comes into contact with - I think it's what keeps him going."

Graham doesn't receive a lot of care, though there's help at hand in case he falls or anything happens. He goes out in his chair on his own, shops and cooks meals for himself.

He and Paul go to galleries or out for a drink when they see each other. "Once he took me to a church that he goes to in Soho," says Paul. "The vicar was really pleased to meet me, he didn't even know Graham's name or anything about his story."

For many it is hard to start to understand, let alone empathise with, the enormity of the change that has led to the situation that Graham now finds himself in. "Extreme aphasia is worse than suddenly being dropped into another country that has a completely different language and mode of communication," explains Rudd.

But in Graham's case, he is tantalisingly close to the normality he knew. He can understand everything, yet his ability to only say "yes" and "no" isolates him. People can only ever guess at what it is that he actually wants to say.

One of Graham's paintings was damaged shortly before he had his stroke. He hasn't been able to repair it

"Imagine coming out of the cinema with your mates and not being able to say anything when they ask 'What did you think?'" says Paul. Often airing views and opinions are the tools that people use to sculpt and define who they are and what they stand for - part of how people present their uniqueness to others. Like the majority of things in Graham's life, this expression of individuality has become immensely difficult.

In the future, what does Graham want? To paint again, to read, to make more waistcoats?

"Mmm, mmm, and urr…" Yes, but there is something else.

"Love, a boyfriend, to go on dates," says Paul.

"Mmm, mmm," says Pawley.

"He got me to contact a guy that he used to see before he had his stroke but I think he's moved out of London now. There are loads of dating apps but for Graham I think it's going to be something that will happen with someone he meets face-to-face.

"That's the next step, I think," says Paul. "He'd love to have a relationship again, just the same as everybody else."

Pictures by Ed Ram

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.