Inside Iran’s Revolutionary Courts

- Published

After Iran's Islamic Revolution secretive courts were set up to try suspected ideological opponents of the regime, with no jury, no defence lawyers and often no evidence beyond a confession extracted from the defendant by means of torture. Those who survived them still bear the psychological scars today.

In the living room of their flat in Calgary, Canada, Shohreh Roshani and her mother Parvin are watching a flickering video. Shohreh has her arm around her mother, and both women are weeping softly.

The grainy footage, which only recently came to light, is of a trial in 1981 and shows the final hours in the life of Shohreh's father, Sirus.

Shortly after it ended, he and the other six defendants were taken away and shot.

Their crime was to have been leading members of a religious minority called the Bahais - heretics, in the eyes of the rulers who had swept to power two years earlier in Iran's Islamic revolution

Former members of the Shah's government were the first targets of their revolutionary justice, but the Bahais were also high on the list.

After Roshani and the other Bahai leaders were seized, the only news that emerged was a letter from another member of the group, Kamran Samimi to his wife Farideh.

"Don't worry," it said. "We are all happy together and we are being treated well."

But two weeks later they were dead.

In the early days of the Revolutionary Court, trials were usually held in secret, with no defence lawyers and no jury. Some lasted no more than a few minutes.

"There was no need to investigate if people had committed a crime," says Iranian academic Dr Majid Mohammadi. "Just being against the regime was enough."

In the case of the Bahai leadership the proceedings lasted for a couple of hours. The defendants can be seen in the footage sitting on a row of chairs facing the judge, who can be heard constantly berating and interrupting them as they try to respond to a series of Kafkaesque charges.

Sirus and Parvin Roshani

"The clear pattern in trials before the Revolutionary Courts is not giving the defendants an adequate opportunity to contest the evidence against them," says Payam Akhavan, a former UN prosecutor, and an expert on the courts.

"Very often there is little to no evidence against them at all."

There is a marked and painful contrast in the footage between the articulate and well- mannered tone of Sirus Roshani and his colleagues, and the crude hectoring of the judge. It ends abruptly before the verdict is announced.

A witness told Parvin later that the firing squad cut them down before they had even finished saying their final goodbyes to each other.

That year, 1981, had been a turning point in Iran - the moment when the new Islamic Republic had begun to face serious opposition.

The People's Mujahedin, a group originally allied to the clerics who led the revolution, had taken up arms against the government and as many as 1,000 state officials had been killed in a wave of bombings over the summer.

In response, the authorities launched a ruthless crackdown.

Thousands of people suspected of belonging to the Mujahedin, and also to leftist opposition groups, were arrested and sent before the Revolutionary Courts.

Among them was Shokoufeh Sakhi, an 18-year-old left-wing activist, who was taken from the family home, in front of her distraught parents, sister and baby son.

Shokoufeh Sakhi describes interrogation

"The look on their faces will always be with me," she says. "I thought, this is the last time I will ever see them."

Sakhi was taken to a detention centre in Tehran where she was beaten and interrogated for three months before being brought before a Revolutionary Court.

"My own interrogator stood behind me," she remembers. "The interrogators would interrupt and say she hasn't co-operated, she's stubborn. Give her the most severe punishment."

The courts took their cue from the father of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, who had declared that confession was the "best evidence", thus dispensing with the need for either witnesses or other evidence.

In order to obtain the desired confession, torture was routine.

"I was handcuffed to the ceiling for six or seven hours," says Abbas Rahimi, a young man accused of giving weapons from a state firearms depot to the People's Mujahedin.

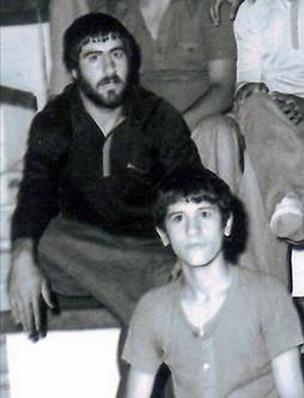

Abbas Rahimi (left) as a young man

"They shaved my head and made me eat my own hair. That's the kind of thing they did."

Shokoufeh Sakhi was sentenced to five years in jail, Abbas Rahimi to 10.

Before either was released, though, the authorities began to worry about the destabilising effect of allowing all the jailed dissidents back into society. The long-running Iran-Iraq war had just finished, Ayatollah Khomeini was unwell, and the clerics feared for the future of the regime.

It was Ayatollah Khomeini himself who came up with the solution, according to Hadi Ghaemi, a leading New York-based Iranian human rights activist.

"It began with a written fatwa," he says, "[It] says we have to verify the loyalty of these prisoners, and anyone who is not repentant should be executed."

So in the summer of 1988, thousands of prisoners who had served their sentences were brought before special three-man tribunals, which came to be known as the "Death Commissions".

The justice they dispensed was swift and brutal, and to the survivors it seemed terrifyingly arbitrary.

"They chose people at random, from different cells," says Shokoufeh Sakhi. "We were all waiting for our turn to come."

Abbas Rahimi was asked to sign a piece of paper expressing repentance, and he complied.

"They would say, go and sit down over there on the right," he remembers." And the people who were sitting on the left would be taken out and executed."

He survived, but his two sisters, Mehri and Soheila, did not.

"The mass executions were held in secret," says former UN prosecutor Payam Akhavan. "Many were quietly hanged in mass groups and their bodies dumped in mass graves."

But the Death Commissions ended as suddenly as they had started and the survivors, Shokoufeh Sakhi among them, were quietly released.

To this day the Iranian government has not publicly acknowledged what happened.

The Revolutionary Courts continued to function in the years that followed, but in the mid-1990s changes were made allowing defence lawyers to be present during interrogations and trials - except in cases involving national security, when it was at the discretion of the judge.

A new generation of lawyers emerged during this period, who were prepared to take on political cases, often at considerable risk to themselves. One of them was Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi.

"As a result of my activities my sister and my husband have been to jail," says Ebadi. "I've been to jail too and I've been threatened with death on several occasions."

It took the protests following the disputed elections of 2009, however, to bring the Revolutionary Courts fully out of the shadows.

After a week of unprecedented street demonstrations, the country's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei intervened, calling in a sermon at Friday Prayers in Tehran for the demonstrations to stop.

Very quickly, the protesters were violently dispersed. Thousands were arrested and before long mass trials were being shown on television.

Among the defendants were student activist Omid Montezari and Hossein Rassam, a political analyst at the British embassy. Montezari had been taking part in the protests, while Rassam had been monitoring them as part of his job.

Unlike their counterparts from the 1980s, and some others who took to the streets in 2009, neither was physically tortured. Instead they were subjected to a subtler form of pressure.

"When someone turns to you and says your child might get hit by a car, that's not something you can deal with easily," says Rassam, whose only son was 13 years old at the time.

Montezari's father had been executed under the Death Commissions in 1988, and his interrogators constantly reminded him he could share the same fate.

Omid Montezari, who was arrested after attending protests in Iran in 2009

Both recall being made to rehearse their lines and to deliver specially prepared confessions expressing repentance.

Eventually they were released, and by comparison with those who were executed, such as Montezari's cellmate, student activist Arash Rahmanipour, they got off lightly. But the experience has left an indelible mark.

Hossein Rassam is troubled by the fact that in his confession he was forced to implicate three other people.

"For this I can never forgive myself," he says. "I am not the same person as I was before."

Hossein Rassam and his son

Earlier generations who suffered at the hands of the Revolutionary Courts remain similarly haunted.

"I know that because I was in prison my son and my immediate family were all tortured too," says Shokoufeh Sakhi, who now works in Canada as a human rights activist. "My son has been damaged massively. I know those lost years will never come back. This will always stay with me, but I can't change who I am."

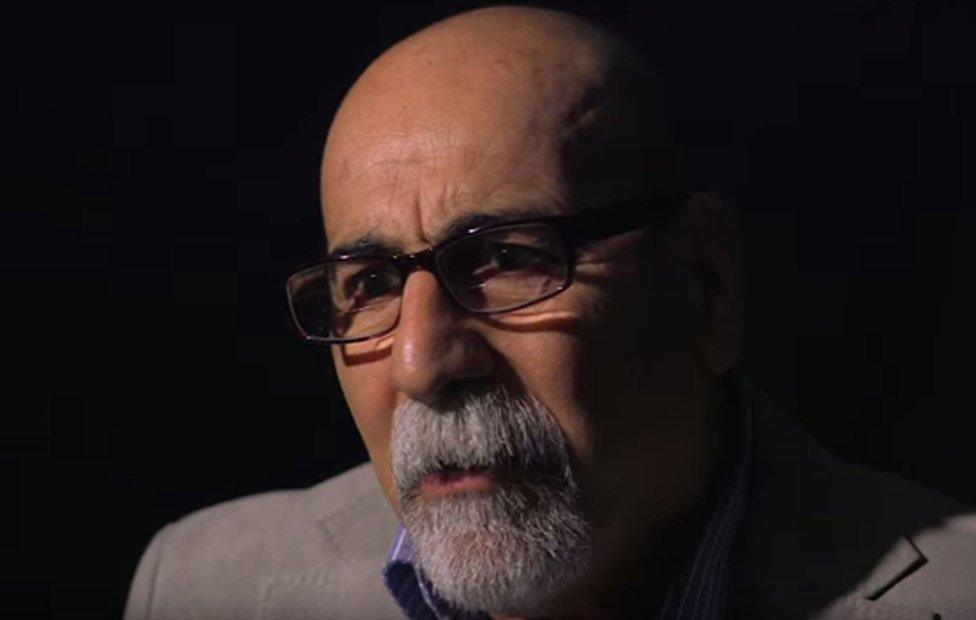

Abbas Rahimi, now 62, lives in London.

There's a deep sadness in his eyes. It's hard to recognise him in the photograph of a jaunty young man taken before his arrest.

"Of course it affects you," he says. "You think about it from time to time. You remember your family, the children. They're always the ones who haunt you the most."

His teenage nephew is one of those who died - arrested to provide information about another family member, he was beaten to death in jail.

In Calgary, Parvin and Shohreh Roshani who left Iran in 1995, still think of Sirus every day of their lives.

Shohreh remembers him as a man dedicated to his family and his job as a doctor, who loved swimming and hiking.

She gazes at the last blurry image of her father on the screen - seven men, sitting side by side, already understanding the fate that awaits them.

"When I was in Milan I saw the Last Supper," she says. "It's so beautiful. I wish I could paint. I would have turned this into a painting."

More from the Magazine

Thirty-five years ago this week, Iraq invaded Iran and what has been described as the 20th Century's longest conventional war began. Both sides suffered terrible casualties but they had different motives for fighting and now, looking back, two soldiers see their experiences in a very different light, writes Mike Gallagher.

Iranian Revolutionary Justice, directed by Mark Williams for BBC Persian, will be shown on BBC World on Saturday 17 October at 04:10, 15:10 GMT; and Sunday 18 October at 09:10, 21:10 GMT

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.