The day Iceland's women went on strike

- Published

Forty years ago, the women of Iceland went on strike - they refused to work, cook and look after children for a day. It was a moment that changed the way women were seen in the country and helped put Iceland at the forefront of the fight for equality.

When Ronald Reagan became the US President, one small boy in Iceland was outraged. "He can't be a president - he's a man!" he exclaimed to his mother when he saw the news on the television.

It was November 1980, and Vigdis Finnbogadottir, a divorced single mother, had won Iceland's presidency that summer. The boy didn't know it, but Vigdis (all Icelanders go by their first name) was Europe's first female president, and the first woman in the world to be democratically elected as a head of state.

Many more Icelandic children may well have grown up assuming that being president was a woman's job, as Vigdis went on to hold the position for 16 years - years that set Iceland on course to become known as "the world's most feminist country".

But Vigdis insists she would never have been president had it not been for the events of one sunny day - 24 October 1975 - when 90% of women in the country decided to demonstrate their importance by going on strike.

Instead of going to the office, doing housework or childcare they took to the streets in their thousands to rally for equal rights with men.

It is known in Iceland as the Women's Day Off, and Vigdis sees it as a watershed moment.

"What happened that day was the first step for women's emancipation in Iceland," she says. "It completely paralysed the country and opened the eyes of many men."

Banks, factories and some shops had to close, as did schools and nurseries - leaving many fathers with no choice but to take their children to work. There were reports of men arming themselves with sweets and colouring pencils to entertain the crowds of overexcited children in their workplaces. Sausages - easy to cook and popular with children - were in such demand the shops sold out.

It was a baptism of fire for some fathers, which may explain the other name the day has been given - the Long Friday.

"We heard children playing in the background while the newsreaders read the news on the radio, it was a great thing to listen to, knowing that the men had to take care of everything," says Vigdis.

As radio presenters called households in remote areas of the country to gauge how many rural women were taking the day off, the phone was often answered by husbands who had stayed at home to look after the children.

As I talk to Vigdis in her home in Reykjavik, she has on her lap a framed black-and-white photograph of the rally in Reykjavik's Downtown Square - the largest of more than 20 to take place throughout the country.

Vigdis, her mother and three-year-old daughter are somewhere in the sea of 25,000 women, who gathered to sing, listen to speeches and talk about what could be done. It was a huge turnout for an island of just 220,000 inhabitants.

At the time she was artistic director of the Reykjavik Theatre Company and abandoned dress rehearsals to join the demonstration, as did her female colleagues.

"There was a tremendous power in it all and a great feeling of solidarity and strength among all those women standing on the square in the sunshine," Vigdis says. A brass band played the theme tune of Shoulder to Shoulder, a BBC television series about the Suffragette movement which had aired in Iceland earlier that year.

Sticker distributed to participants - reading "Women's Day Off"

Women in Iceland got the right to vote 100 years ago, in 1915 - behind only New Zealand and Finland. But over the next 60 years, only nine women took seats in parliament. In 1975 there were just three sitting female MPs, or just 5% of the parliament, compared with between 16% and 23% in the other Nordic countries, and this was a major source of frustration.

The idea of a strike was first proposed by the Red Stockings, a radical women's movement founded in 1970, but to some Icelandic women it felt too confrontational.

"The Red Stockings movement had caused quite a stir already for their attack against traditional views of women - especially among older generations of women whom had tried to master the art of being a perfect housewife and homemaker," says Ragnheidur Kristjansdottir, senior lecturer in History at the University of Iceland.

But when the strike was renamed "Women's Day Off" it secured near-universal support, including solid backing from the unions.

"The programme of the event itself reflected the emphasis that had been placed on uniting women from all social and political backgrounds," says Ragnheidur.

Women's suffrage around the world

Iceland was not the first country to give women the right to vote, but it was well ahead of the curve.

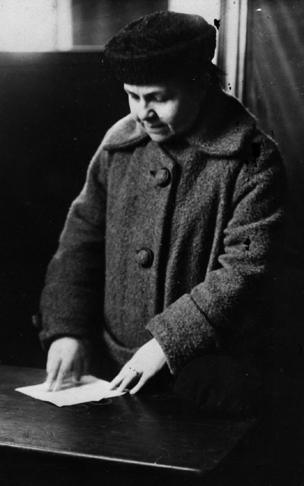

A woman votes in Russia, 1917

1893 New Zealand

1902 Australia

1906 Finland

1913 Norway

1917 Soviet Russia

1918 Canada, Germany, Austria, Poland

1919 Czechoslovakia

1920 US and Hungary

*

1928 UK (limited suffrage from 1918)

*

1971 Switzerland

Among the speakers at the Reykjavik rally were a housewife, two MPs, a representative of the women's movement and a woman worker.

The final speech was given by Adalheidur Bjarnfredsdottir, head of the union for women cleaning and working in the kitchens and laundries of hospitals and schools.

"She was not used to public speaking but made her name with this speech because it was so strong and inspiring," says Audur Styrkarsdottir, director of Iceland's Women's History Archives. "She later went on to become a member of parliament."

Members of the committee that prepared the "Women's Day Off"

In the run-up to the event the organisers succeeded in prompting radio, television and national newspapers to run stories on low pay for women and sex discrimination. The story attracted international attention too.

But how did the men feel about it?

"I think at first they thought it was something funny, but I can't remember any of them being angry," says Vigdis. "Men realised if they became opponents to this or refused to grant women leave they would have lost their popularity."

Vigdis Finnbogadottir and Margaret Thatcher, 1982

There were one or two reports of men not behaving as Vigdis describes. The husband of one of the main speakers was reportedly asked by a co-worker, "Why do you let your woman howl like that in public places? I would never let my woman do such things." The husband shot back: "She is not the sort of woman who would ever marry a man like you."

Styrmir Gunnarsson was at the time the co-chief editor of a conservative newspaper, Morgunbladid, but he had no objection to the idea. "I do not think that I have ever supported a strike but I did not see this action as a strike," he says. "It was a demand for equal rights… it was a positive event."

No women worked at the paper that day. As he remembers it, none of them lost pay, or were obliged to take the day as annual leave, and they returned at midnight to help get the newspaper finished. It was shorter than usual, though - 16 pages instead of 24.

"Probably most people underestimated this day's impact at that time - later both men and women began to realise that it was a watershed," he says.

At the same time, he points out there have always been strong women in Iceland - something reflected in the (fictional) Icelandic Sagas.

"Our past is in our blood and through the centuries life was difficult in Iceland," Styrmir says. "Those who survived must have been strong."

The Women's Day Off is generally regarded in Iceland as a seminal moment, though at least one member of the Red Stockings regarded it as a missed opportunity - a nice party that did not really change anything.

Vigdis disagrees. "Things went back to normal the next day, but with the knowledge that women are as well as men the pillars of society," she says. "So many companies and institutions came to a halt and it showed the force and necessity of women - it completely changed the way of thinking."

Five years later, Vigdis beat three male candidates to the presidency. She became so popular that she was re-elected unopposed in two of the three next elections.

Other landmarks followed. All-women shortlists made an appearance in the 1983 parliamentary election, and at the same time a new Party, the Women's Alliance, won its first seats. In 2000, paid paternity leave was introduced for men, and in 2010 the country got its first female prime minister, Johanna Sigurdardottir - the world's first openly gay head of government. Strip clubs were banned in the same year.

Saadia Zahidi, head of Gender Initiatives at the World Economic Forum (WEF) says Iceland still has further to go.

"While more women than men are enrolled in university, the workplace gender gap persists," she says.

"Women and men are nearly equally present in the labour force - in fact women are the majority across all skilled roles - but they hold about 40% of the leadership roles and earn less than men for similar roles."

Nonetheless, Iceland has topped the WEF's Global Gender Gap Index since 2009. And if at the time of the Women's Day Off only three of the 63 members of parliament were women, the figure is now 28, or 44%.

"We say in Iceland, 'The steps so quickly fill up with snow,' meaning there is a tendency to consign things to history," says Vigdis. "But we still talk about that day - it was marvellous."

More from the Magazine

A century ago, Iceland banned all alcoholic drinks. Within a decade, red wine had been legalised, followed by spirits in the 1930s. But full-strength beer remained off-limits until 1 March 1989. Megan Lane asks why it took so long for the amber nectar to come in from the Icelandic cold.

Listen to Vigdis Finnbogadottir on Witness, on the BBC World Service

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.