The US inmates charged per night in jail

- Published

A widespread practice in the US known as "pay to stay" charges jail inmates a daily fee while they are incarcerated. For those who are in and out of the local county or city lock-ups - particularly those struggling with addiction - that can lead to sky-high debts.

David Mahoney is $21,000 (£13,650) in debt. Not from credit cards. Not from school loans.

He's accumulated the massive tab because of the days he spent locked up in the local jail in Marion, Ohio, which is a small town with a major heroin epidemic. Mahoney, a lanky 41-year-old, has struggled with addiction since he was a teenager, eventually stealing to fuel his habit. He got caught a lot, even burgling the same bar twice.

"The urge to use cocaine and crack - that's what it led to it. Once I start using there's no going back for me," he says.

Today, he's 14 months sober, and is a resident and employee of the Arnita Pittman Community Recovery Center, a sober living house on the northern edge of town. His counsellor says he is doing "awesome" and he hopes to one day to become an addiction counsellor himself.

But while Mahoney may have left his habits behind, he can't shake his debt. It has accumulated over 15 years of trouble with the law and is a separate charge from the restitution he must pay to the victims he stole from, or any administrative costs he has incurred by going to court.

It comes from a daily "pay-to-stay" fee - sometimes called "pay for stay" - that he was charged by the local jail, the Multi-County Correctional Center. He was charged $50 each day he spent in jail, plus a $100 booking fee. It works almost as if he checked into a hotel and got a bill when he checked out.

"Obviously, it's my fault I'm in the situation I am in. I'm trying to start over," he says. "People that end up in jail are usually down on their luck anyway. They're going through some trials and tribulations in life. Why focus on the people who are already struggling?"

He is not alone - the guy that lives down the hall from him at the sober living house owes nearly $22,000. Yet a third resident has them both beat at $35,000. Anecdotally (and confirmed by the Multi-County jail's administrator) they know of at least one other man in town who owes $50,000.

"I got collection people calling on it," says Brian Reed, the man with the $35,000 tab. "I just get hopeless."

Brian Reed

Combined, five residents of the tiny Arnita Pittman Center represent over $100,000 worth of pay-to-stay debt. None of them believe they will ever be able to pay it off. Both Reed and Mahoney are still paying off their fines and restitution, not to mention school and medical bills. They're working on their other debts, but they don't see the point of putting money towards their pay-to-stay.

Even Marion County Sheriff Tim Bailey, who is supportive of the fees, was surprised when he heard how high some of the debts had climbed.

"Wow," he told BBC News. "That's outrageous."

There's an estimated $10bn worth of criminal justice debt in the US, held by 10m men and women who have had some interaction with the criminal justice system. It's a type of debt that's not well understood or studied.

Today, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Ohio released the first comprehensive study, external looking specifically at pay-to-stay policies and how they are used in the state. At a press conference, the legal group called for the practice to be eradicated.

"Pay-to-stay jail fees devastate prisoners and their families," said Mike Brickner, the group's senior policy director, in a prepared statement.

After requesting records from all 75 city and county lock-ups in Ohio, the study shows that 40 charge per diem fees in a patchwork style. Where you are arrested and jailed can make a huge difference in whether and how many fees are assessed - the fees affect mostly rural and suburban counties, and some charge as little as $1 or as much as $66 a day. The ACLU found former inmates with debts ranging from several hundred dollars up to $35,000.

"We're hearing from people who are claiming this is going on their credit scores and preventing them from doing all sorts of things," says Brickner.

According to Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior counsel in the Brennan Center's Justice Program at New York University's School of Law, these types of fees are legal in nearly every state - only Washington DC and Hawaii do not have a law authorising pay-to-stay charges. Her group is working on a multi-year project to show what the revenue and costs are of these programmes around the country, but at the present time the practice remains largely unexamined.

"You're really shifting the onus onto the poorest members of our society in the justice system. If they can't pay their family members pay, or their grandmothers pay," she says.

In the aftermath of Ferguson, courts around the country from Michigan to Texas have been called out for using law enforcement as a revenue-generating arm of the local government. Brickner says pay-to-stay policies are just another example of attempting to make money off poor people caught in the criminal justice system.

"They simply don't work. People are coming out of jail with hundreds or thousands of dollars' worth of debt, and if you are a returning citizen, having that is just another albatross around your neck," he says. "It's a programme that maybe feels good to people who have a tough on crime mentality, but in fact it's sort of a fruitless exercise."

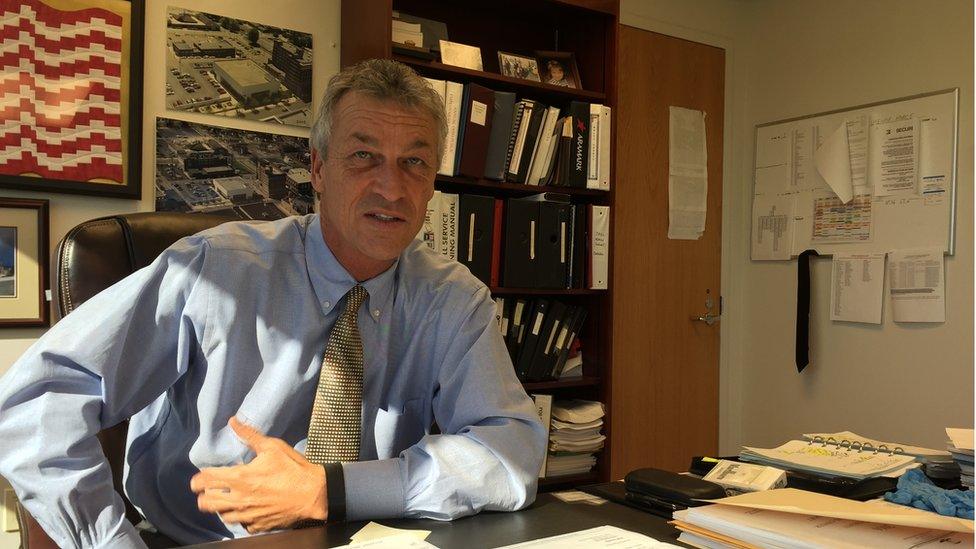

Multi-County Correctional Center administrator Dale Osborne

Dale Osborne, the jail administrator at the Multi-County Correctional Facility, makes the same argument for pay-to-stay that's been made since the practice became legal in Ohio in the mid-90s.

"It offsets the expenses that the taxpayers are required to have," he says. "The more revenue I can generate within a facility, the less the taxpayers have to pay."

But he admits that while the programme bills for about $2m a year, they collect only about $60,000-$70,000. That's about a 3% collection rate.

"If we lost the ability to have a pay-for-stay programme here I'm not going to have any huge heartache over the loss of it," he says.

The sum that is able to be collected doesn't go straight into the county coffers, either - the jail contracts with a company called Intellitech Corporation, which acts as a collections agent, sending letters and making phone calls to former inmates. If the debtor sends a check to Intellitech or arranges a payment plan with them, 30% of the money goes to the county and 70% goes to Intellitech.

According to the company's president, John Jacobs, Intellitech runs pay-to-stay programs in 12 counties in Ohio and in six other states. He says that by becoming the "Walmart" of pay-to-stay collections, his company makes the practice viable for counties.

Why are so many Americans behind bars?

"It's something we'll continue to do because we believe in it," he says, calling it "a win for the taxpayers and a win for the sheriff."

Other jurisdictions around the country have opted to run pay-for-stay programmes for themselves. Macomb County, Michigan, has one of the oldest programmes, and in the past reported that the practice has collected $18m over 26 years. But Sheriff Tony Wickersham says that revenue has dropped off since 2009, and in the last three years collected only an average of $240,000 a year with two full-time staffers running it.

The cost of running it is almost equal to what they bring in, he says.

Many counties who've had similar results or even operated the programme at a loss have abandoned the practice. Others say even the small amounts yielded are worth the effort, and one programme in Dakota County, Minnesota, specifically puts all its pay-to-stay revenue into programmes to assist with prisoner re-entry.

"Our goal is to reduce recidivism. If we can use that money to turn around and not see them again it's well worth it," says chief deputy Joe Leko.

In a 2005 study, external of 224 local jails across the country, researchers found that while per-day fees generated millions in revenue, jail administrators rated the practice as their "most effective" policy almost as often as they cited it as their "least effective" policy.

How strictly counties choose to go after outstanding debts varies quite a bit as well. Many debtors around the state interviewed by the ACLU of Ohio described "collections agents as very aggressive and the threat of credit reporting was used," says Brickner. The study found that 26 counties in the state pursue debts with collections.

The Multi-County Correctional Center in Marion, Ohio

In Michigan, Macomb County's website says that it "often uses legal action and or collections agencies. We sue approximately 1,200 cases per year…We have garnished wages, bank accounts, and tax refunds. We have filed and collected with execution against property (taken vehicles, boats, mobile homes, etc)". Wickersham says they only pursue cases where the inmate has found employment after release.

Although Intellitech acts as a collections agent for its clients, Jacobs says they do not report any of the debt to credit reporting agencies. In a national survey, jail administrators around the country were split as to whether or not they believed collections processes were worth pursuing.

Brickner of the ACLU argues that regardless of whether or not debts are aggressively pursued, the practice is fundamentally flawed.

"Nationally and here in Ohio we are really in a place where we want to see reform of our criminal justice system," he says. "I'm really hopeful that through the data and through these stories people will see this is a policy that just doesn't work. There are better things we can do here in Ohio."

Both Mahoney and Reed say their families have stepped in over the years to try to pay down the debt, but at this point they have stopped. Mahoney is concentrating on his school debt so that he can go back to class and finish his associate degree.

Although he says he has little hope that his pay-to-stay debt will ever be wiped out, he hopes the practice will fall out of favour.

"I would love to see it stopped and quit affecting people's live by charging them for being down and out," he says.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.