Korea's hidden problem: Suicidal defectors

- Published

All over the world, people flee in their millions from tyrannous regimes, but how often do they find the better life they were hoping for? In South Korea, statistics indicate that a startling number of defectors from the North end up taking their own lives.

You always hear of the celebrity defectors. They write best-selling books and appear on television. They can earn tens of thousands of dollars for an evening at a speaking engagement. They are eloquent as they tell their harrowing stories of dangerous flights from extreme oppression.

But there is sometimes a darker side to the stories of those who flee their homeland.

In South Korea, the statistics reveal a truth. The country's unification ministry says that over the past 10 years, 6% to 7% of defectors who have died killed themselves. But in recent months there has been a big rise - according to the ministry, 14% of deaths among defectors this year have been suicides. That is much higher than among the population in general, and South Korea consistently has the highest suicide rate of all the 34 industrialized countries in the OECD.

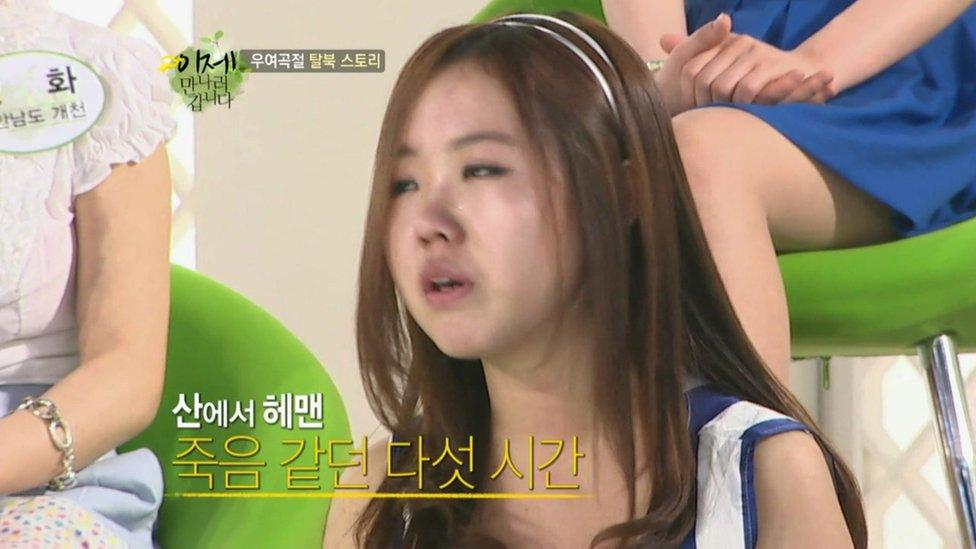

North Korean defectors tell their harrowing stories on a South Korean TV show

There are a number of factors involved. One is that the home they've left is close but unreachable. Another is that their new economic reality can be very different from the glamorised life portrayed in the South Korean soap operas smuggled into the North.

Kim Song-il is now in his seventh line of business since he defected 14 years ago. He's been a bus driver, a building labourer and has run a restaurant.

Now he's started his own business selling chicken pieces. He buys whole chickens and has hired a handful of employees to cut them up and bag them for freezing to be sold - the price of the parts combined is greater than the cost of the whole.

It's a struggle. "When my earlier businesses failed, I tried to kill myself three times," he says. "I had to keep reminding myself how I risked my life just to get here."

Part of his difficulty, he says, is that he was a military officer in the North and was used to giving orders. Taking orders as an employee in capitalism has not been easy.

Last year, there were 1,400 defectors. The flow is all one way - North to South.

Or nearly all one way. Forty-five-year-old Kim Ryen-hi gave a tearful press conference recently and announced that she wants to go home. Four years ago, she arrived in South Korea via China and Thailand but now misses the North dreadfully.

"Freedom and material and other lures of any kind, they are not as important to me as my family and home," she said. "I want to return to my precious family, even if I die of hunger."

Kim Ryen-hi is still in South Korea, unable to return to the North

She is very much an exception - and there are those who succeed in the South. Lee Yung-hee has enterprise written right through her. She defected 14 years ago and now runs a busy restaurant - Max Tortilla - two hours outside Seoul.

In the North, she'd never heard of this classic Mexican dish but when she reached the South she initially got a job selling kebabs - meat in a roll - and thought that adding rice would suit Korean taste even more. The result, she discovered, was akin to a burrito, so she went into the burrito business - very successfully. Initiative and hard work paid off.

"When I first arrived here the South seemed so different," she says. "In order to succeed, I had to learn everything from scratch."

Lee Yung-hee (foreground) built a successful business from scratch

Defectors get three months' training when they arrive but critics of the system say that's not enough to learn new skills. The government replies that the defectors themselves don't want prolonged periods of schooling.

Some Christian groups provide vocational training and say that what works best is training in simple but useful skills like making coffee to serve in a cafe.

But the lack of opportunities, beyond humble jobs like this, is one source of discontent.

According to one survey 50% described their status in the North as "upper" or "middle" class, but only 26% said they fell into this category in the South. The vast majority - 73% - described their new status as lower class.

Andrei Lankov, a historian at Kookmin University in Seoul who has also studied in Pyongyang, says the problem is that skills acquired in the North are insufficient for the modern South Korean economy. Doctors who defect, for example, often fail to get jobs in South Korean medicine.

Doctors who defect find it hard to get work in hospitals such as this one in Seoul

In his opinion, this has implications for unification whenever (and if ever) it happens.

"Can a graduate of a North Korean medical school hope to get a license in post-unification Korea if all his (or, more likely, her) medical knowledge is taken from poorly translated Soviet textbooks that are a few decades old?" he asks in a story for the NK News website, external.

And would a South Korean company hire a technician "whose job for decades has principally consisted of dogged - and often ingenious - efforts to keep Soviet-era vintage equipment working?"

That is a dilemma for the future. In the present, the hidden problem consists of desperate North Koreans who are lonely and adrift in South Korea, teetering on the edge of taking their own lives, and sometimes tipping over the edge.

Watch Stephen Evans's video, filmed for the Victoria Derbyshire programme.

More from the Magazine

Fifteen years ago, Kim Cheol-woong was a successful pianist living in North Korea - but his life suddenly changed when someone heard him playing a Western love song.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.