Fire, plague and royalty - as seen by diarist Samuel Pepys

- Published

Samuel Pepys never intended his famous diaries to be made public. But without them, we would be denied his very colourful eyewitness accounts of 17th Century London life. How did he manage to be in the right place at the right time?

The National Maritime Museum, external in Greenwich is seeking to find the answer in a new exhibition looking at Pepys's meteoric rise from relatively humble beginnings.

"The 1.25 million words in Samuel Pepys' diaries give us the richest record we have of Britain in the 1660s," says co-curator Robert Blyth.

"It was a terrifically turbulent and exciting time. You get the end of the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell, the restoration of Charles II, and then the plague and the Great Fire of London.

"Pepys was there for it all."

Samuel Pepys, by John Hayls

Pepys sat for this portrait several times over a number of weeks. Dressed in a hired gown, he wanted to look like a cultured and sophisticated man about town.

But he paid for such a look in more ways than one - writing in his diary that he almost broke his neck looking over his shoulder to hold the pose for artist John Hayls.

From a modest background - his father was a tailor - Pepys rose to be a senior naval administrator, an MP and president of the Royal Society.

"He was a real social climber," says exhibition co-curator Kris Martin. "Partly self-made, but he owes a lot to his distant cousin Edward Montagu who played a major role in his success."

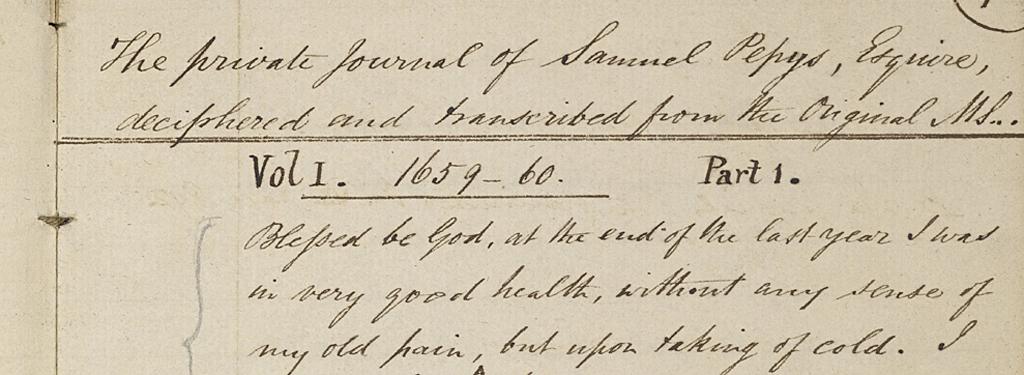

First transcriptions of Samuel Pepys's diary, by John Smith, 1825 (detail)

Pepys's diaries were written in a form of shorthand - partly to conceal the content, and partly so Pepys could write quickly.

For more than 100 years the volumes sat on the shelves of Magdalene College, Cambridge - with all the other books he had bequeathed after his death. The first transcriptions appeared in the early 1800s - with the full, more candid versions only published in the 1970s.

"He was an appalling womaniser by modern standards," says Blyth. "He may well have been horrified that his diary is now laid bare for all to see. It is like your whole Facebook account being broadcast to the world."

This next painting marks the restoration of the English monarchy at the end of Cromwell's Commonwealth - with Charles II's state entry into London on 22 April 1661, the day before his coronation.

"Pepys rushed to Cornhill to watch it. He got a room, some cake and wine - and admired the ladies," says Kris Martin. "But he also mentions how incredible the scene was. Sparkling diamonds woven into fabric and crowds cheering."

Charles II's cavalcade through London, by Dirk Stoop (detail)

The white arches in the distance were specially made temporary structures - constructed of plaster and paper mache - designed to show the strength of the restored monarchy.

Charles II's cavalcade through London, by Dirk Stoop

The scene is in marked contrast to the cold January day in 1649, when Pepys bunked-off school and headed to Whitehall to watch the execution of Charles I.

"Pepys was a republican and supported Cromwell as a young man," says Martin. "But he switched, on the advice of his cousin Edward Montagu, just at the right time as the republic was crumbling."

Charles II in Coronation Robes, by John Michael Wright

"And Pepys was, of course, at Westminster Abbey to witness to coronation of Charles II," says Robert Blyth.

"In his diary he complains about not being able to hear the music too well. And he doesn't see all of it. It is a very long ceremony, and he leaves early to go to the toilet."

The coronation painting above also stresses that the newly restored monarchy is secure - adds Martin.

"The King's loins are on display. It is very much about 'I am fertile, I will give you children, we will rule a long time'."

Portrait of Nell Gwyn, after Sir Peter Lely

The actress Nell Gwyn, reclining in the painting above, was Charles II's mistress.

Pepys called her "pretty, witty Nell".

"She had a real talent for comedic roles," says Blyth. "And avid theatregoer Pepys took delight in watching women on stage - looking at the female form."

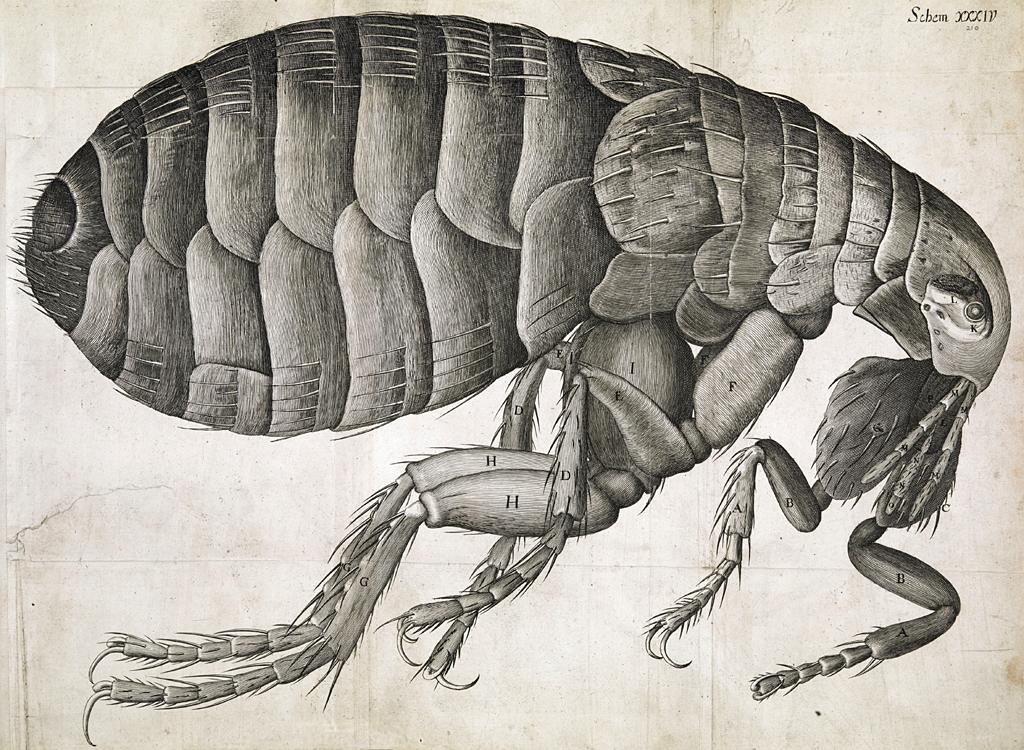

The up-close image of a flea below comes from a publication which Pepys described as "the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life".

Micrographia, by Robert Hooke, was the first book to illustrate insects and plants as seen through microscopes.

Flea viewed under the microscope, from Robert Hooke, Micrographia

And it was through rat fleas that the deadly bubonic plague began to sweep through London at the end of 1664.

"Pepys was constantly worried about the plague," says Martin. "He loses friends. His baker. His butcher. And he was obsessed with death rates, checking them weekly.

"He is also concerned about wearing his new wig, as it may have been made from the hair of plague victims."

He never got the disease.

Pepys's accounts of the Great Fire of London in September 1666 are, says Blyth, "without doubt some of the most affecting and extraordinary entries in his diary".

"For the whole year the population of London had a great sense of foreboding, because the year had the number of the devil in it - 666. There was just this sense that something appalling was going to happen."

The Fire of London, September 1666 - unknown artist

The fire started at the king's bakers in Pudding Lane, and quickly spread west through a tinder-dry London, buffeted by a strong easterly wind.

Famously, Pepys buried a parmesan cheese and some wine in his garden.

"He offered his advice to King Charles and his brother, James the Duke of York," says Blyth. "He was granted an audience because the duke was Pepys's boss in the navy - and the capable Pepys would be able to get the instruments of government working together to fight the fire."

Blyth says that once the fire was out, Pepys was invited to dinner and, as typical with middle-class Londoners, the conversation turned to property prices.

"And how landlords would now, because more than 100,000 people had been made homeless, be able to command greater rents for those properties which had survived."

In his role as Lord High Admiral, James, Duke of York, would not have usually dressed quite so flamboyantly as he is in the painting below.

James, Duke of York, by Henri Gascar

"For this portrait, the future King James II is shown in the stylised outfit of Mars the Roman God of War," says Blyth. "But the duke was a skilled commander, not just a figurehead."

And for most of Samuel Pepys's career as a naval administrator, James would have been his boss.

Dutch attack on the Medway, The Royal Charles carried into Dutch Waters, by Ludolf Backhuysen

England's main nautical rival at that time was the Dutch Republic.

The painting above shows the humiliating raid on the Medway in 1667 - during the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

Pictured in the centre is the English flagship, the Royal Charles - which was seized by the Dutch. The same ship had brought Charles II back from exile in 1660.

Blyth says Pepys was not implicated in the incident but he was clearly worried for the future of the monarchy and any implications for his career - noting in his diary that it was not his fault.

"I have, in my own person, done my full duty, I am sure," he writes.

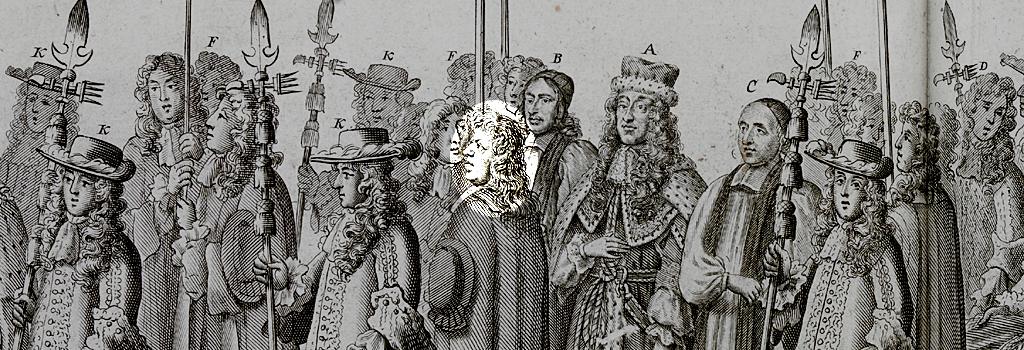

Samuel Pepys may have been only in the congregation at Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Charles II, but by the time Charles' brother James came to the throne in 1685, Pepys's social standing was such that he was one of the coronation canopy bearers.

The History of the Coronation of James II and of Queen Mary, by Francis Standford

This etching shows the procession - with Pepys on the front left corner. He took on the role because, by that time, Pepys had become a Baron of the Cinque Ports - in Kent and Sussex.

The History of the Coronation of James II and of Queen Mary, by Francis Standford (detail)

Robert Blyth and Kris Martin both stress the value of Pepys's daily observations, because they paint a more colourful, human picture of life in the 17th Century.

"He was dashing around London soaking up all that was going on," says Blyth. "Food and drink. Gossiping about who was in and out of favour. Moaning about traffic jams. You can impose 21st Century London on what he wrote."

"Pepys could have thrown his private diary on the fire but he didn't," adds Martin. "And because he didn't, we have learnt so much. We have the diary of an everyman, but also a mover and shaker in society. He was a very modern character. There is a bit of Pepys in all of us."

Portrait of Samuel Pepys in 1689, by Sir Godfrey Kneller

Samuel Pepys: Plague, Fire, Revolution can be seen at the National Maritime Museum, external, Greenwich, London from 20 November 2015 to 28 March 2016.

All images subject to copyright.