The last woman left on a derelict street

- Published

This shot from Google Streetview shows Lynda cleaning the pavement

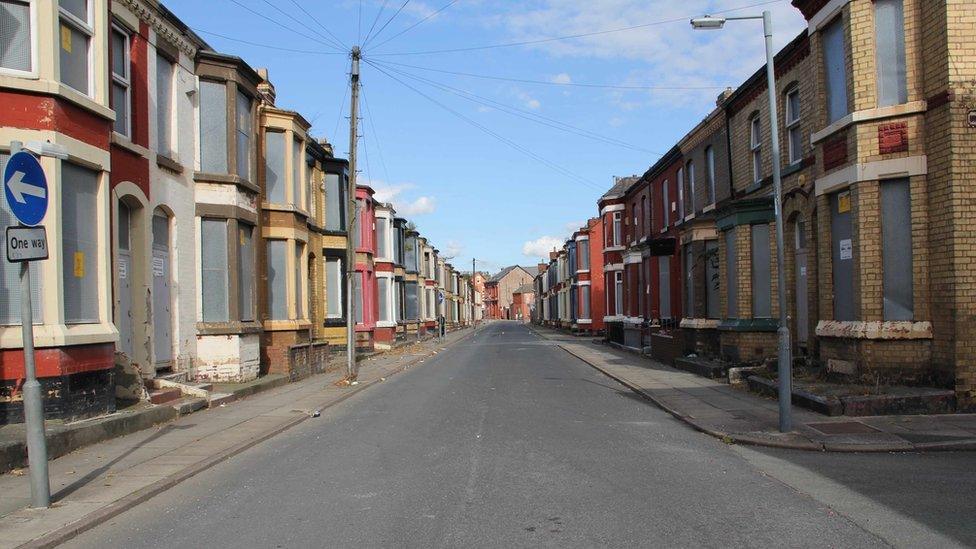

Houses on an all but abandoned street in Liverpool are being sold for £1. But 30 years ago it was a vibrant inner-city street, so what went wrong, asks Stephanie Power.

If you type Garrick Street, Liverpool, into Streetview, you get a picture of a row of empty terraced houses with one woman dressed in jeans and a jumper, washing the pavement outside her house.

This street doesn't look empty because it's a quiet day, it looks empty because no-one lives there. Almost no-one. Lynda Hunter, her husband George, and another man a little further down the road are Garrick Street's only residents.

All the other houses are "tinned up", their windows blocked with metal against vandals. They were earmarked for demolition nearly a decade ago as part of a housing policy which would have seen these Victorian terraces replaced by new-builds.

Walking along the street, you feel like you're in an unused film set. It's eerily quiet, but you can feel the spirit of the people who used to live and play here.

"I moved in 27 years ago," says Lynda "when I married my husband. This was his house. It was a lovely street then. We had good neighbours - families, elderly people - a good community. Summer days were the best. We'd have street parties and we would sit out into the early evenings."

And while the street may be reminiscent of a forgotten film set, it is in a bustling area - located just off Smithdown Road, one of the main routes into the city centre. A new secondary school has opened yards away and there is a big student population here. The local paper gives you "11 Signs Smithdown Road Is On The Up". A giant street party celebrated "Smithdown's" renaissance last summer.

Lynda has lived on the street for almost three decades

So where is everybody on Garrick Street?

Garrick Street was a mix of owner-occupiers like Lynda and others who rented privately or lived in social housing.

In 2002 the Labour government introduced the Housing Market Renewal Initiative. The idea was to regenerate areas that were in "housing market failure".

There was a lot of money to be had, over £300m in Merseyside alone and, as Liverpool City Council deputy mayor Ann O'Byrne says, the administration at the time bought as many properties as they could so they could clear streets for housing renewal.

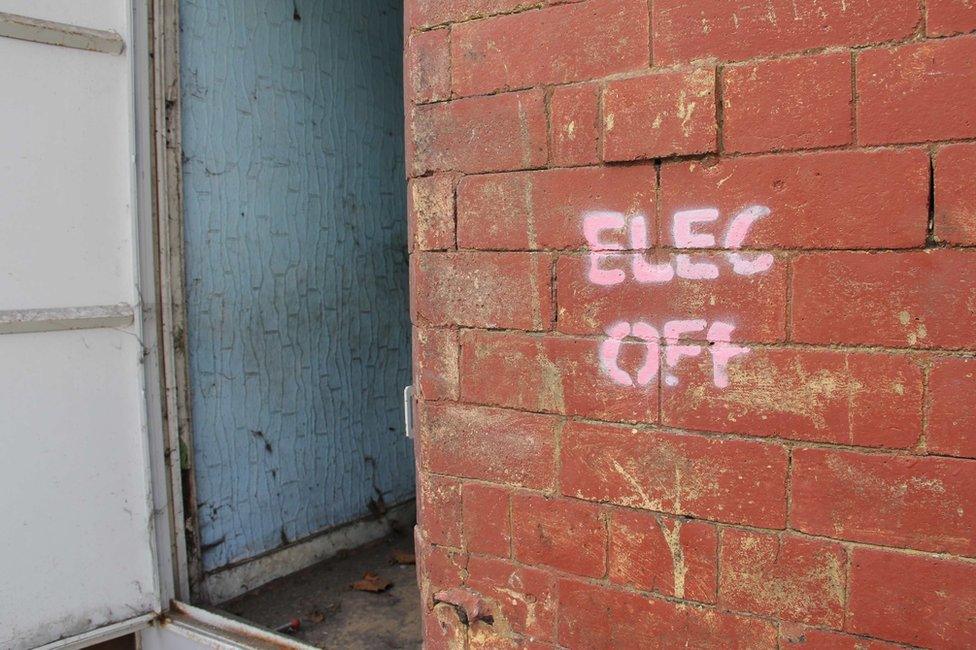

Some of the houses need a lot of restoration work

The initial plans covered an area of 40,000 houses which were to be considered for refurbishment or clearance. The majority of properties were listed for refurbishment but over 7,000 were to be demolished. The Garrick Street houses were on that list.

The scale of the project was huge. Maybe too big. The Lib Dem leader of the council from 2005-10, Warren Bradley, has said that, external on reflection, his council had left parts of Liverpool looking like a war zone. "We announced six renewal areas, and in hindsight we should have done it one by one. You can't rip the heart of the community and promise them something in 15 years' time. We should have landscaped areas so that people didn't feel they were living in a war zone."

Lynda says: "The council said they'd done a survey of people on Garrick Street and the majority they had spoken to were unhappy and wanted to move."

But Lynda says the street was fully occupied. People only started moving out once demolition was threatened.

The Garrick Street houses were due to be demolished

Was it that Garrick Street only declined because the council ran it down in order to get HMRI money? Town planner Jonathan Brown followed HMRI closely: "If you draw a red line around an area and say it's unsustainable it becomes unsustainable. You can't get mortgages and it freezes in the very blight it is supposed to resolve."

Meanwhile Lynda says it was terrible watching people leave: "The old lady two doors away, she'd lived here 57 years. She had buried her husband from that house. She had buried her daughter from that house. All her memories were there. She was sobbing the day she left."

The Housing Market Renewal Initiative (or Pathfinders)

The intention was to renew failing housing markets and reconnect them to regional markets

It was launched in 2002 and ran until 2011 when the coalition government ended funding

There were nine Pathfinders schemes in Birmingham/Sandwell, East Lancashire, Hull and East Riding, Manchester/Salford, Merseyside, Newcastle/Gateshead, North Staffordshire, Oldham/Rochdale, and South Yorkshire

Each scheme was allowed relative freedom to develop strategies; their boards were made up of members from local authorities and other key regional and local stakeholders

Source: House of Commons, external

When the coalition government came into power in 2010, HMRI was scrapped. O'Byrne says: "The city lost £120m. And our housing policy was an absolute mess."

Lynda was left in a street with almost no neighbours and no clear plans for her future. "In the last three years, it's been like a warzone. Youths setting fire to vacant properties, lead stolen off the roof, people trying to kick the door in. A couple of weeks ago someone put a brick through my living room window. It's been horrendous."

In January this year the government changed policy again. "The government removed all the powers that local authorities had to do demolition," says O'Byrne.

So the council had to review housing policy again. In 2014 they had run a pilot scheme offering derelict houses to potential residents for £1. In return new owners had to promise to do up the houses and live in them for five years.

The halt on demolition has provided the council with the perfect opportunity to expand the £1 house scheme.

Jayalal Madde, pictured with the mayor of Liverpool, Joe Anderson, bought the first Garrick Street £1 home in December 2014

Garrick Street is one of a handful of streets in Liverpool which will be part of the council's new £1 houses scheme. Called Homes for a £1 Plus, applicants can bid for one of 150 houses as long as they live and work in the city, promise to do it up within 12 months, and live in it for at least five years.

Good news for Lynda surely. The whole of Garrick Street will be refurbished. The community will be rebuilt. "It's too late for me at my age. And it also means my house is only worth £1. The scheme is good for first-time buyers but I need my forever home now. I can't live on a building site for years. I want my grandchildren to be able to stay with me and play out."

Lynda is waiting for the council to move her into a different home elsewhere. And as she plans her move away, upwards of 2,000 people have applied to rebuild Garrick Street and others around it.

O'Byrne says: "What we learned from the pilot is that it's not enough to interview candidates. We need to show them the properties. These are decanted homes. No cables and no pipework. We are talking about four walls and maybe a roof in some cases."

Is a commitment to building a sense of community one of the criteria for those looking for a house for a £1? "Everyone in the pilot says they have put their heart and soul into this. When do you get a chance to do genuine homesteading other than building a house outright yourself. It's such a unique opportunity. They've told us, we're not here for five years. We're here for life."

Meanwhile Lynda shows the plastic sheeting that now protects her bay window from another brick attack. But after living under the threat of demolition for years she is positive.

"I'm looking forward to moving. I'm relieved the council is going to help me at last."

It seems a shame, though, that after 27 years Lynda's time in Garrick Street will end just as the place is about to come back to life.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.