What could possibly go wrong on a spacewalk?

- Published

On Monday, astronauts on the International Space Station carried out a spacewalk in order to perform repairs. Everything went according to plan, but leaving the safety of the station is extremely dangerous and things can go wrong. What do astronauts have to watch out for?

1. Drowning in space

A spacesuit is like a small, individual spacecraft but it can malfunction, as Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano discovered when his helmet started to fill with water during a spacewalk in 2013.

His ventilation system had sprung a leak. Liquid doesn't flow under zero gravity, so the water sat in his helmet covering his eyes and ears, and blocking his nostrils.

At risk of drowning, he had to cut short his spacewalk.

"I started going back to the airlock and the water kept trickling," says Parmitano. "It completely covered my eyes and my nose. It was really hard to see. I couldn't hear anything. It was really hard to communicate.

"I couldn't breathe through my nose - I felt isolated and when I tried to tell ground that I was having trouble finding my way, they couldn't hear me, and I couldn't hear them either.

"Instead of focussing on the problem - which was I may drown with the next gulp of air - I started thinking about solutions."

Parmitano gradually felt his way back to the airlock, past the "no-touch" zones - parts of the ISS where sharp edges could tear his spacesuit - and made it to safety.

Back on board, Luca Parmitano's crewmates scramble to remove his waterlogged helmet

Find out more

Listen to Luca Parmitano who spoke to the BBC World Service radio programme Outlook

Chris Hadfield spoke Newshour, also on the BBC World Service

But he isn't the only person to experience problems with his suit.

On his first spacewalk in 2001, Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield found his left eye suddenly started to sting and fill with tears. The tears formed a blob of fluid that covered his right eye too.

That left him blinded. In space. While holding a drill.

Fearing that the stinging was being caused by a toxic gas leak inside the suit, ground control advised Hadfield to release air to clear out the contaminant - getting rid of breathable air in space went against all of his survival instincts but he did as he was told and it worked.

Eventually his tears flushed the irritant out of his eyes and he was able to see again, so he could stop dumping precious oxygen and finish his spacewalk.

The irritant turned out to be an anti-fogging agent on the inside of his visor.

2. Floating away

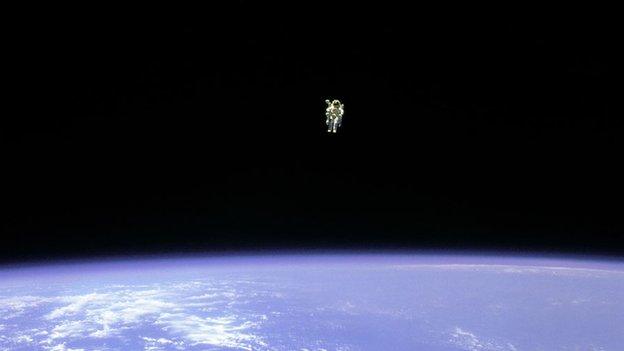

In an rare operation in 1984, American Bruce McCandless used a jetpack to fly 320ft away from his spacecraft

Although no astronauts have drifted off into space, Hadfield says he ranks this as his number one fear - above problems with lift-off or burning up on re-entry.

Anyone going on a spacewalk is constantly attached to the ISS with a retractable 85ft (26m) braided steel tether.

Astronauts typically work in teams of two "buddies" on a spacewalk. When they are still inside the airlock - which separates the inside of the station from the void of space - they tether themselves together.

The first astronaut out of the hatch connects his or her cable to the outside of the hull before anchoring the partner's line outside as well. Spacewalker number two then disconnects from the inside of the airlock and joins the buddy.

This way the risk of becoming detached is small. But if an astronaut is unexpectedly left floating free what are the options?

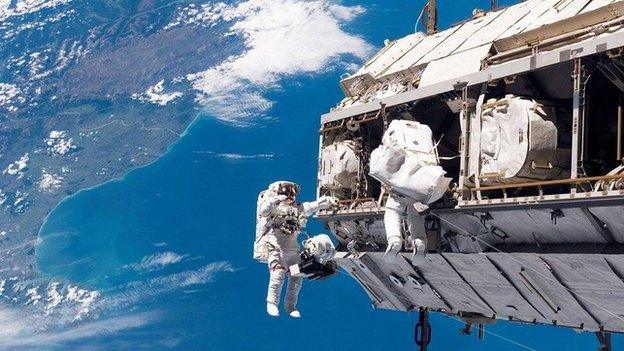

Staying tethered... Chris Hadfield made two spacewalks in a 2001 mission to the ISS

"We're wearing a jetpack and you can pull down this handle and a joystick comes out of a little hidden drawer and pops out in front of you," says Hadfield. "You activate the joystick, and you can fly your jetpack, and grab back on to the space station."

Jetpacks were not available to astronauts Pete Conrad and Joe Kerwin in 1973. They were outside the Skylab space station working on a solar array which was stuck in the wrong position. When the array suddenly deployed fully, both men were thrown off.

Luckily, their tethers held and if subsequent accounts are accurate, so did their sense of humour. Apparently both men returned to Skylab laughing.

3. Boiling blood

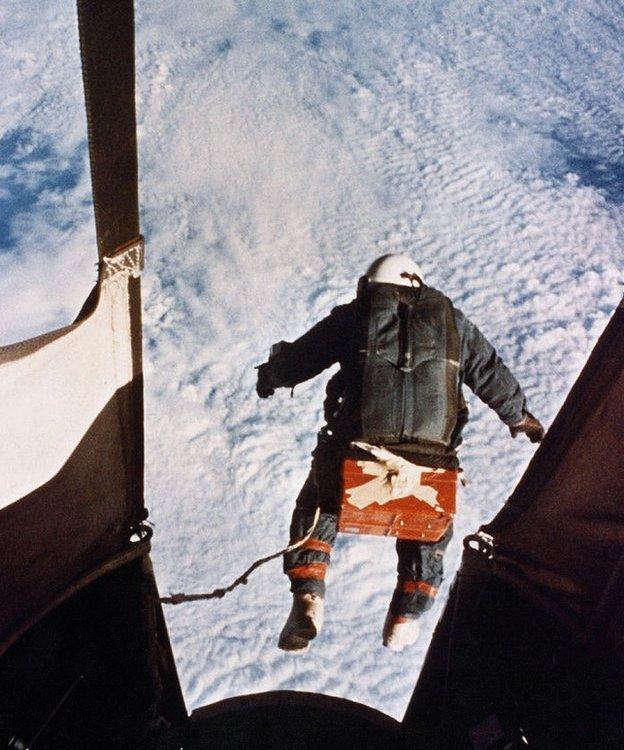

Joseph Kittinger hit 614mph before opening his parachute

The suits worn on a spacewalk are pressurised to protect against the near-vacuum conditions of space and a tear or puncture could have fatal consequences.

Human flesh expands to about twice its normal size in a vacuum, as US Air Force pilot Joseph Kittinger discovered when he made a high-altitude skydive from a balloon in 1960. The pressurisation in his right glove failed as he ascended to an altitude of more than 19 miles above the Earth, and his hand swelled up dramatically.

Undeterred, he jumped anyway, setting several records in the process. Back on the ground, his hand returned to its normal size, but he was lucky - if his helmet, or the body of his suit had depressurised, he would not have survived.

A more immediate concern in the event of a spacesuit being damaged might be the loss of breathable air. If a spacesuit were to rapidly depressurise, an astronaut would pass out after about 15 seconds - the time it takes a body to use up its oxygen.

That's exactly what happened to one Nasa test subject who was exposed to near-vacuum conditions in an accident at a test facility in Houston in 1966. He described feeling the saliva on his tongue bubble before he lost consciousness.

In space, without the pressurisation provided by a spacesuit, body fluids would boil as the gases in them expanded. So if the lack of oxygen didn't kill you, something else would - and quickly.

But small holes in the suit are not necessarily disastrous.

In 2007 American astronaut Rick Mastracchio spotted a small tear in the outer layer of his glove near his left thumb.

Not a big hole - but enough to end Mastracchio's spacewalk early

"I can see the surface under the Vectran material," Mastracchio told ground control. "I don't know where that hole came from."

It was almost a repetition of an incident eight months earlier when US astronaut Robert Beamer had ended up with a 2cm gash in one of his gloves - it was probably damaged on a sharp edge while he transferred newly-delivered equipment from the space shuttle to the ISS. He completed his spacewalk unharmed, but if a cut that size had penetrated the innermost pressurised layer, this would have been an emergency.

The main body of a spacesuit has seven layers of shielding to help protect against micrometeoroids. These small particles of rock weigh less than 1g but their speed relative to the ISS can reach 22,500mph (36,200km/h).

No suit is able to protect a spacewalker from larger objects though. Nasa is tracking more than 500,000 pieces of human-made space junk orbiting Earth - anything from abandoned spacecraft to launch debris. About 20,000 of these items are at least as big as an orange.

4. Exhaustion

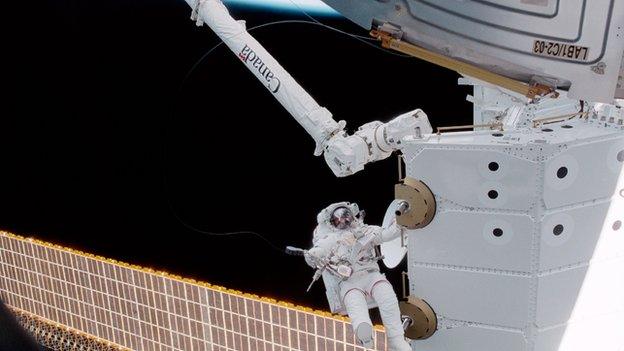

Astronauts spacewalk with dozens of tools strapped to their suits

When they made their debut spacewalk in October, American astronauts Scott Kelly and Kjell Lindgren spent more than seven hours greasing a robotic arm, rigging cables and fitting a thermal cover on an instrument which measures the intensity of light.

Part of the reason spacewalks take so long is that although a 160kg spacesuit is weightless in space, it is still a big, cumbersome piece of kit that is difficult to work in.

"If you were to walk up to someone who was wearing one of the Nasa spacesuits and push on it with your finger, it's at exactly the same pressure as a volleyball, that level of stiffness of material," says Hadfield.

"Every move you make with your body you have to push against that amount of inflated resistance. You come in from a spacewalk absolutely physically whipped, and often you've worn through the skin somewhere - you're bleeding - just because the suit is a misery to work in."

And without gravity holding them in position, spacewalkers cannot simply stand in place to do a task. If they turn a spanner, their body tries to rotate in the opposite direction. So they have to exert themselves all the more just to stay where they are while they work.

"You have to use other muscles to hold yourself steady, so you use twice as much effort basically doing anything on a spacewalk, which is the other reason for taking it slowly," says Hadfield.

When people get tired they can make mistakes. If you slip up while using a power drill at home you might wind up in hospital. But when you are orbiting Earth at an altitude of 250 miles (400km), calling an ambulance is not an option.

5. The great unknown

Getting out was easy... Alexey Leonov was the first person to walk in space

Spacewalks have come a long way since Soviet cosmonaut Alexey Leonov carried out the first one in 1965. He spent only 12 minutes outside his Voskhod spacecraft but even so disaster almost struck.

Soviet engineers had failed to account for Leonov's suit expanding under the zero-pressure conditions of space. When he tried to get back into his spaceship, he could not fit through the hatch. He had to release a valve to partially depressurise his suit so he could squeeze back inside.

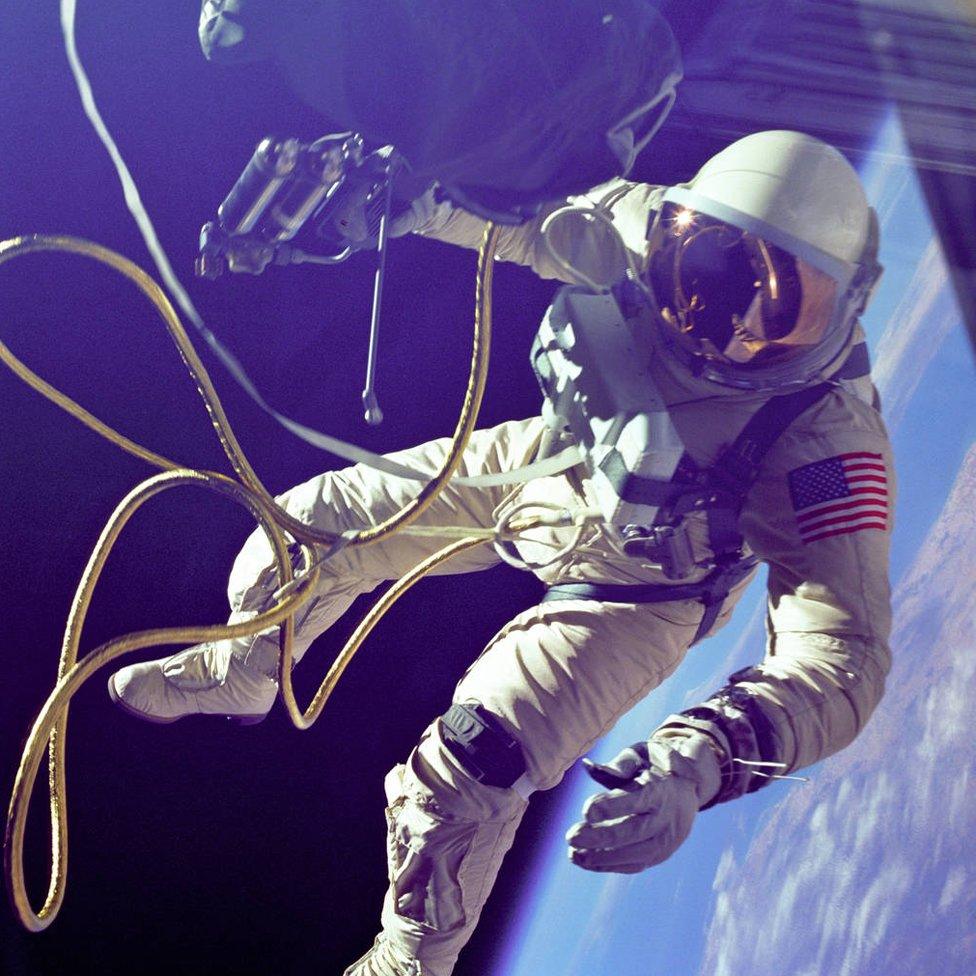

When Ed White became the first American to do a spacewalk later the same year, he probably wasn't aware of Leonov's narrow escape, which was only revealed much later.

But White did know there was a something wrong with his own hatch when he left his spacecraft - there was a faulty spring which made it hard to open and close. When he went back inside, for a short time it looked like he might not be able to secure it. If that had been the case the Gemini IV might not have been able to return to Earth.

In addition, his mission commander, James McDivitt, who stayed inside their capsule, had instructions to cut White loose if he ran out of air or lost consciousness.

The list of spacewalk unknowns has shortened considerably since 1965. But they still exist.

"Astronauts do their worrying in advance," says Hadfield. "We try and spend years worrying every little detail out of everything that can go wrong, so that when the actual day arrives you are not incapacitated by fear.

"Nobody really wants a scared, surprised astronaut."

Ed White on his spacewalk

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published21 December 2015