Stark images of Shackleton's struggle

- Published

A century ago a ship sank beneath the ice of the Weddell Sea off Antarctica. Sir Ernest Shackleton had been counting on Endurance to help him make it ashore, ahead of a trek across the continent past the South Pole.

Now, newly digitised images capturing the last days of Endurance, and the crew's subsequent struggle to stay alive, are on show at the Royal Geographical Society, external in London.

"Frank Hurley's beautiful image of Endurance confuses people because the sails are up," says the Antarctic historian, Meredith Hooper, who has curated the exhibition, Enduring Eye.

"And yet she is beset in the ice. The sails are up because they had reached a moment when the crew thought they could break free."

Shackleton - with the help of his 27-man crew - had planned to cross Antarctica from coast to coast, picking up supplies left by a second team as he neared the other side.

"He minded very much that he wasn't the first at the South Pole," says Hooper.

"He saw the Endurance expedition as the last great Antarctic achievement."

But he never made mainland Antarctica. After a six-day gale in January 1915, the Norwegian-built ship became trapped in ice in the Weddell Sea.

She would then drift in the ice for ten months - with Shackleton and his men living on board.

Their daily lives were recorded by Australian photographer Frank Hurley.

Hurley's images show how the crew survived during that uncertain period - when they were at the whim of the shifting pack ice.

The photograph above shows a football match on the ice.

Meredith Hooper says it was taken in mid-February 1915, after the men had tried to release Endurance for one last time, but then had to accept they were stuck - with the cold and dark Antarctic winter approaching.

"Shackleton saw the match as a good way to let off steam. They had even flattened the ice to create a pitch."

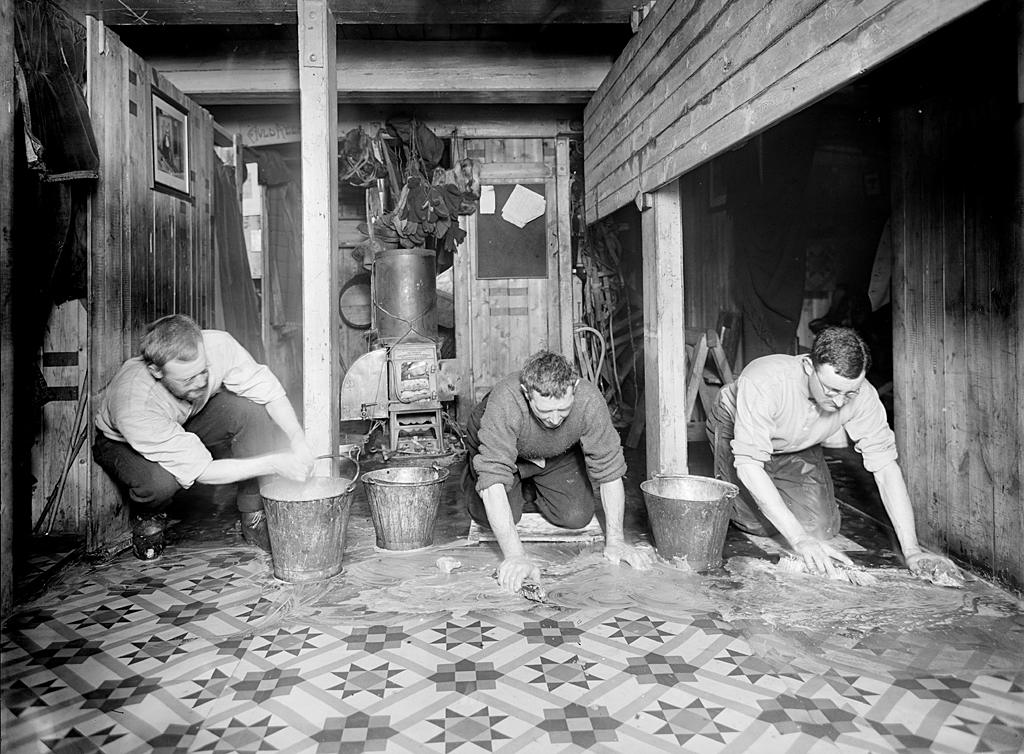

Endurance's role changed from that of a ship to that of a shore station. Many of the crew were assigned new sleeping quarters in the hold - mockingly they called it The Ritz.

The tradition of scrubbing the floor remained, and everyone - except perhaps Shackleton himself - took their turn.

In this photo we see Jock Wordie the expedition geologist on the left - with Third Officer Alfred Cheetham in the centre - and Alexander Macklin the ship's doctor on the right.

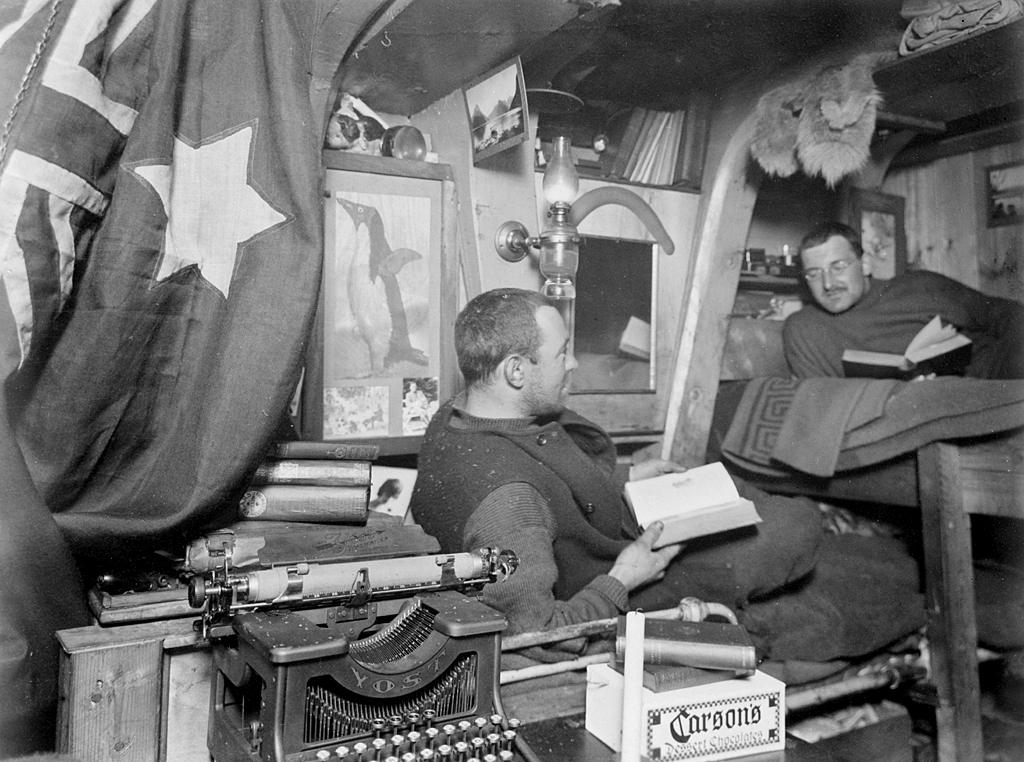

Photographer Frank Hurley has placed himself in this picture - which shows him playing chess to fill the long dark winter days of mid-1915.

"We know this was taken before May 1915," says Meredith Hooper.

"Because in May they all had a fit of madness and decided to shave their heads. And in this photo, Hurley, on the left, still has his hair."

Hurley's hair is growing back in the next photo, which was taken in his cabin. Macklin the doctor is on the right.

For the first time, Hurley's images have been scanned digitally direct from the original glass plates on which they were taken - revealing details never seen before. The mid-ground and background in each shot is crisper and sharper.

"You can see the Australian flag, a penguin picture and a boomerang," says Hooper.

"But I particularly like the Carsons chocolates by Hurley's bed. On Saturday nights the crew would toast sweethearts and wives - and for those who didn't want alcohol, like Hurley, Shackleton had provided chocolates."

Back in "The Ritz", this photo shows the midwinter dinner to celebrate the shortest day of the year - 22 June 1915.

The cabin is adorned with the UK, Australian and New Zealand flags.

"They had peas," says Hooper. "But no one had yet started eating. Knives and forks are poised."

"On the left is Perce Blackborow, a stowaway who was given the job of steward."

The same space is transformed for this posed image which shows what Endurance's crew did on a typical day. Scientific experiments, typing and reading.

The steward, Blackborow, is again in shot on the left. He is carrying a large block of ice to be turned into drinking water.

Here, a group of men are gathered around the ship's stove during the night watch.

"There would normally be only one or two men on the night watch," says Hooper. "But people on that shift got extra food, and so your mates would suddenly appear.

"Hurley is expressing intimacy and comradeship."

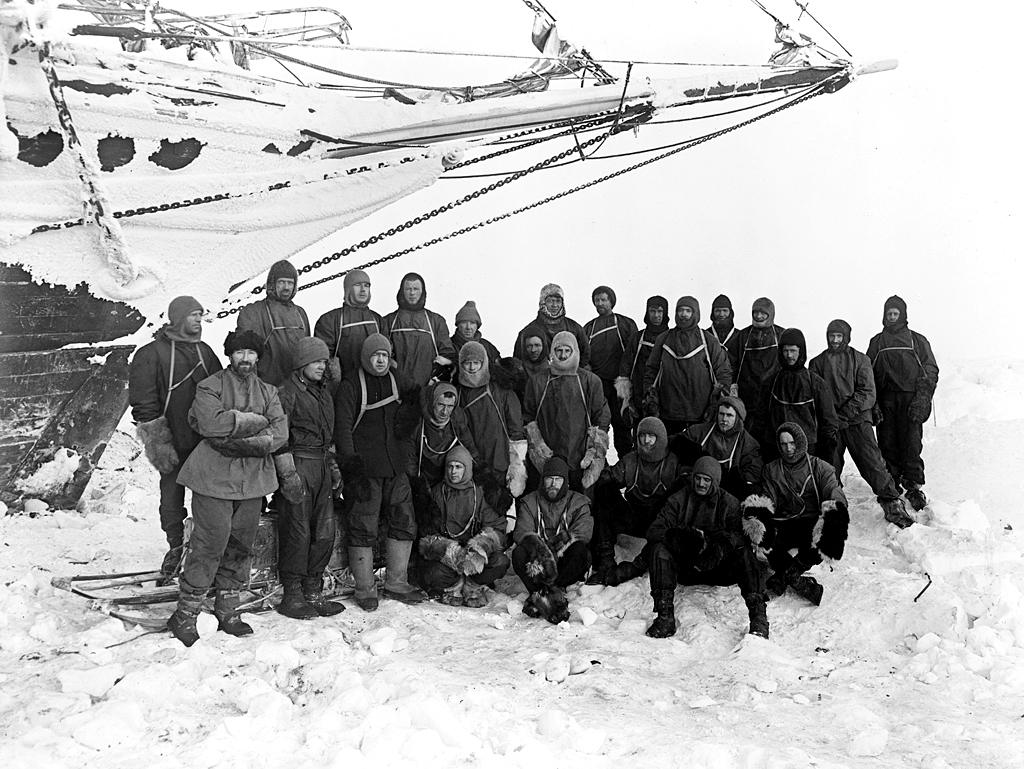

Looking at the next two images, Hooper says they were both taken on the same day - possibly 1 September 1915.

First, Hurley is shown taking a photo with his heavy equipment - under the prow of Endurance and standing on big chunks of crumbling ice.

And then there is an image of the rest of the crew.

"Personally I think the group shot was taken as a morale booster," says Hooper. "You can see the light is back, spring is coming, and all the men are dressed in new kit. It's very much a posed photo."

Dogs were on board ship with the crew. Shackleton had planned to cross Antarctica with them.

But in time, as feeding the animals becoming an issue, the dogs had to be put down.

"They found it very difficult," says Hooper.

Endurance was subjected to huge pressure from the ice - and there were moments when she listed, but then righted herself.

But by the end of October 1915, with water leaking in, the crew took the decision to decamp on to the ice.

"They described a terrifying experience," says Hooper.

"They had to move their tents twice in one night, with the ice cracking and squealing. And then there was the sound of the ship suffering - it was crying like a wounded animal."

Endurance sank on 21 November 1915.

Here, outside their tent on the ice, Hurley on the left and Shackleton on the right.

Hurley is cutting fine strips of seal blubber - fuel for the portable stove which sits between them, and which he invented.

"It was also endlessly wet," says Hooper. "And when the right day came - with some wind and some sunshine - they tried to dry all their stuff."

Hurley was forced to become more selective with his subject matter as time went on - and in the end he destroyed 400 of his negatives, keeping only 120, of which the Royal Geographical Society now looks after 68.

By April 1916, in three small boats which had been taken off Endurance, Shackleton and his crew left the floating ice and started an arduous voyage to uninhabited Elephant Island.

It took them seven long days - but miraculously, everyone survived.

Then - in one boat from Elephant Island - Shackleton took five of his crew on a 750-mile journey to South Georgia, where there were whaling stations. Finally he managed to raise the alarm.

This last image shows the Yelcho - a Chilean steamer - returning to pick up the remaining 22 men from Elephant Island at the end of August 1916.

"The story ended successfully but at any point - almost daily - it could have ended in disaster," says Hooper.

"The story which had to be told was the success of survival - and Frank Hurley's images are terribly important in that narrative."

Enduring Eye: The Antarctic Legacy of Sir Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley, external can be seen at the Royal Geographical Society in London from 21 November 2015 until 28 February 2016.

All images subject to copyright.