Beyond 'he' and 'she': The rise of non-binary pronouns

- Published

In the English language, the word "he" is used to refer to males and "she" to refer to females. But some people identify as neither gender, or both - which is why an increasing number of US universities are making it easier for people to choose to be referred to by other pronouns.

Kit Wilson's introduction when meeting other people is: "Hi, I'm Kit. I use they/them pronouns." That means that when people refer to Kit in conversation, the first-year student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee would prefer them to use "they" rather than "she" or "he".

As a child, Wilson never felt entirely female or entirely male. They figured they were a "tomboy" until the age of 16, but later began to identify as "genderqueer".

"Neither end of the [male/female] spectrum is a suitable way of expressing the gender I am," Wilson says. "Sometimes I feel 'feminine' and 'masculine' at the same time, and other times I reject the two terms entirely."

Earlier this year, Wilson asked friends to call them "Kit," instead of the name they (Wilson) had grown up with, and to use the pronoun "they" when talking about them.

Glossary

Transgender: Applies to a person whose gender is different from their "assigned" sex at birth

Cisgender: Applies to someone whose gender matches their "assigned" sex at birth (ie someone who is not transgender)

Non-binary: Applies to a person who does not identify as "male" or "female"

Genderqueer: Similar to "non-binary" - some people regard "queer" as offensive, others embrace it

Genderfluid: Applies to a person whose gender identity changes over time

See also: A guide to transgender terms

Sharing one's pronouns and asking for others' pronouns when making introductions is a growing trend in US colleges.

For example, when new students attended orientation sessions at American University in Washington DC a few months ago, they were asked to introduce themselves with their name, hometown, and preferred gender pronoun (sometimes abbreviated to PGP).

"We ask everyone at orientation to state their pronouns," says Sara Bendoraitis, of the university's Center for Diversity and Inclusion, "so that we are learning more about each other rather than assuming."

A handful of universities go further and allow students to register their preferred pronouns in the university computer systems - and also a preferred name.

At the University of Vermont, which has led this movement, students can choose from "he," "she," "they," and "ze," as well as "name only" - meaning they don't want to be referred to by any third-person pronoun, only their name.

"It maximises the student's ability to control their identity," says Keith Williams, the university's registrar, who helped to launch the updated student information system in 2009. Most people stick to the default option, "none", which means they are not registering a pronoun - presumably because they are content to let people decide whether they are a "he" or a "she".

Out of about 13,000 students currently enrolled, some 3,200 have entered preferred names in the system, and about half of them have specified preferred pronouns, Williams says. He adds that this doesn't necessarily mean they are transgender - they could be non-transgender students specifying "he" and "she".

At Harvard University, which followed Vermont's example at the beginning of this academic year, about half of the approximately 10,000 students registered in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences have specified preferred pronouns, and slightly more than 1% of those - about 50 out of 5,000 - chose pronouns other than "she" or "he", according to registrar Mike Burke.

At most other US universities the growing use of "non-binary" pronouns remains less formalised but is often encouraged in various ways. Signs and badges found throughout campuses display slogans such as Pronouns Matter or Ask Me About My Pronouns. Professors may be invited to training sessions at the start of each year and are sometimes urged to include their pronouns in their email signature, for example, "John Smith (he/him/his)".

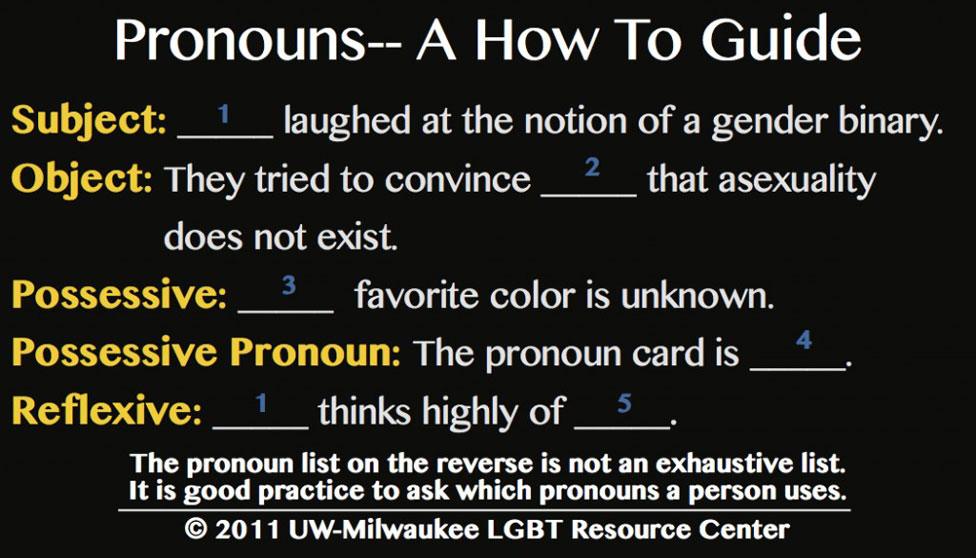

A card developed by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee LGBT Resource Center in 2011 has been widely reproduced and distributed across the US.

One side of the card lists eight pronouns, from "ey" to "zie," and illustrates how they change depending on their role in a sentence. Instead of "he/she," "him/her," "his/her," "his/hers," and "himself/herself" it would be:

"ey," "em," "eir," "eirs," and "eirself", or

"zie," "zim," "zir," "zirs," and "zirself"

The other side of the card has fill-in-the-blank sentences to give people an opportunity to practise using the unfamiliar pronouns.

"The intention behind it was to ensure that the campus was fostering an inclusive environment," says Jennifer Murray, the director of the resource centre.

All the pronouns on the card were already in use, Murray says, either among students or members of Milwaukee's LGBT community. Although it might have been simpler to suggest just one non-binary pronoun, she says the staff of the resource centre didn't want to "limit folks' choices".

The alternatives to "he" and "she" are myriad. Wikipedia's gender-neutral pronouns page lists 14 "non-traditional pronouns" in English, though three are variants of "ze". Other online resources for the non-binary community, however, offer hundreds of options, external.

The First Grammar Book for Children (1900)

Some terms come from foreign languages - such as the German-inspired "sie" - others from fiction. For example, "ze" and "per" are the pronouns of a future utopia Marge Piercy describes in her feminist sci-fi novel Woman on the Edge of Time (1976). Some are drawn from the plant or animal worlds, or refer to mythical beings with which the individual may identify.

It's is not the first time people have tried to coin new pronouns. Writers have long been frustrated by the lack of a neat way to refer to someone of unknown gender - "he or she" is clunky, and if you use it several times in quick succession, "your writing ends up looking like an explosion in a pedants' factory", as Guardian columnist Lucy Mangan once put it.

A linguist at the University of Illinois, Dennis Baron, has catalogued dozens of proposed gender-neutral pronouns, external, many - including "ip," "nis," and "hiser" - dating back to the 19th Century.

Most of these made little impact, though one - "thon", a contraction of "that one" - got into two American dictionaries.

Overall, though, Baron calls the gender-neutral pronoun an "epic fail", external and reckons that new pronouns such as "ze" may not survive. But both he and Sally McConnell-Ginet, a Cornell University linguistics professor who researches the link between gender, sexuality, and language, think the singular "they" - as used for example by Kit Wilson - has a chance of success.

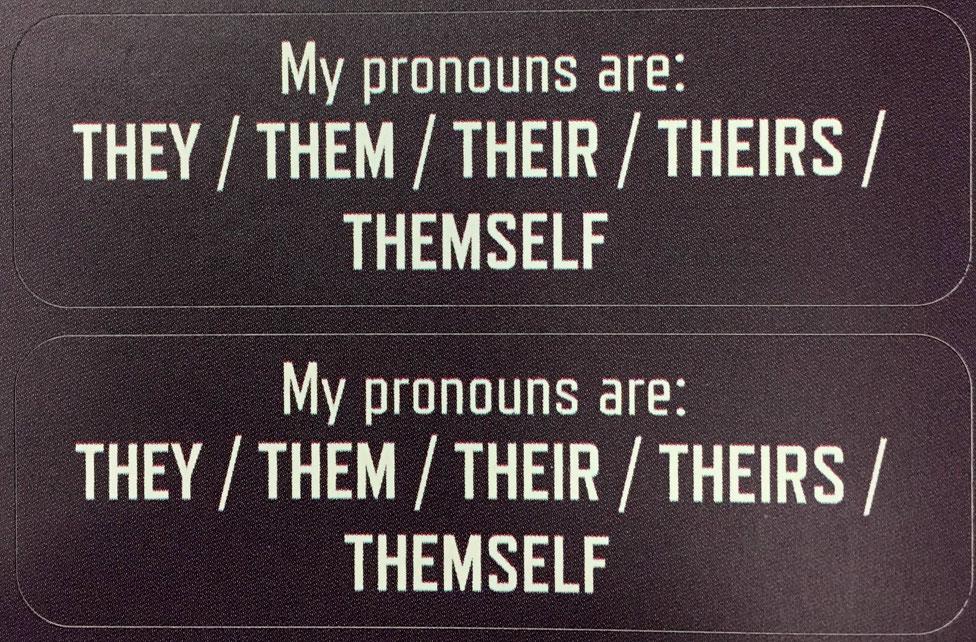

Stickers available at the University of Ohio

This use of "they" annoys some grammarians. While it does feel natural for most English speakers to say something like "Someone lost their wallet," critics argue that "they" should really only be used to refer to plural nouns. And even those comfortable with "Someone lost their wallet" may have doubts when "Someone" is replaced by a person's name.

It's for this reason that when the pronoun registration system was developed at the University of Vermont in 2009, professors at first argued "ze" would be acceptable, but "they" would not. "They" was only added as an option in 2014.

But English has a precedent for a plural pronoun coming to be used in the singular - the pronoun "you". Until the 17th Century a single person was addressed with "thou" and "thee". Later "you" became perfectly acceptable in both plural and singular. Neither McConnell-Ginet nor Baron sees any reason why the same could not happen with "they".

Last week Washington Post copy editor Bill Walsh sent an email to the newsroom, external - probably the most popular email he will ever send, as he put it - saying the singular "they" was sometimes permissible, and "also useful in references to people who identify as neither male nor female".

Non-binary in the UK

Most students have "some level of understanding about pronouns", which was not the case a few years ago, says the National Union of Students' LGBT officer, Fran Cowling. NUS name badges now include space for preferred pronouns.

Cambridge University students started a campaign called Make No Assumptions about a year ago. One of its badges (above) prompts readers to ask about the wearer's pronouns. Another has empty spaces for pronouns to be filled in.

Emrys Travis, Cambridge University Student Union's LGBT+ campaigns officer, uses "they," "them," and "their," but also "ey," "em," and "eir" with trans friends. "A lot of them mess up - repeatedly, often," Travis says. "As long as I think they're trying, it doesn't bother me."

Travis asked their director of studies to email each of their (Travis's) lecturers with a request to use "they" and "them" when referring to Travis and none objected. "Cambridge, in general, is a great place to be trans," they say.

However, learning to use new pronouns or the singular "they" is not easy.

Like Harvard, Ohio University gave students the option to register their preferred name and pronoun this year, but not all professors were ready for it. Some thought "they" was a typo on their student rosters, says LGBT centre director delfin bautista (bautista writes their name without any capital letters).

Slip-ups with preferred names are rarer than with preferred pronouns, bautista says, but can happen too. Calling someone by their rejected birth name is termed "deadnaming". More broadly, referring to a person in a way that does not reflect their gender identity is called "misgendering".

When students suspect that professors may not get the point of gender-neutral pronouns, they may play it safe and stick with "he" or "she".

Sarah Grote, an Ohio University student, uses "they/them" with close friends but hasn't entered this in the student information system to avoid inconveniencing or alienating professors. "I still need their recommendations… and this is still south-eastern Ohio," Sarah says.

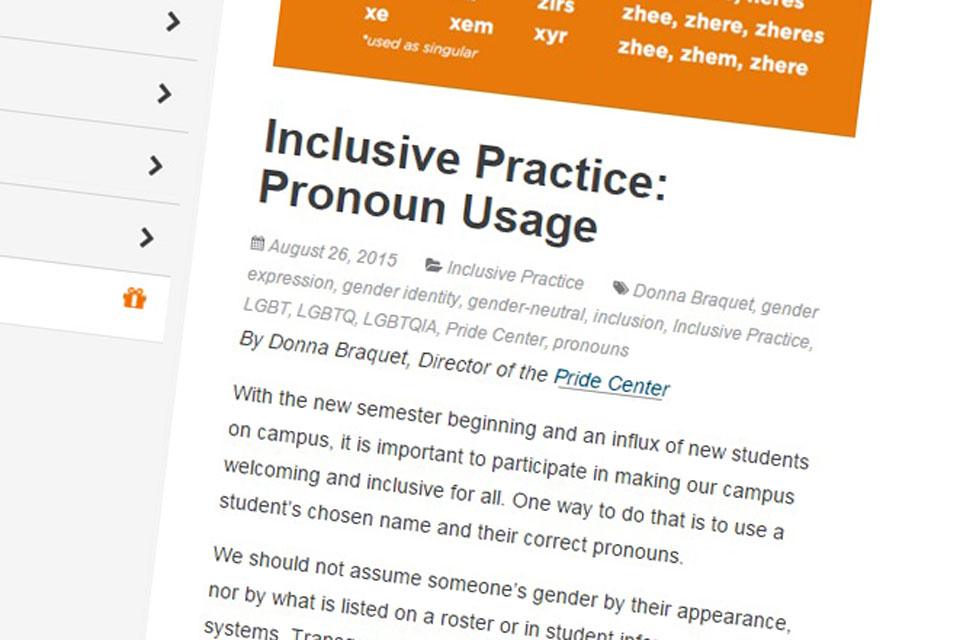

In another socially conservative region, one university had to swiftly backtrack after tentatively starting a discussion about pronouns this summer. Donna Braquet, director of the Pride Center at the University of Tennessee posted an explanation of gender-neutral pronouns on the university website in August and encouraged people on campus to ask one another about their pronouns.

The deleted page from the University of Tennessee website

The goal was to make the climate more trans-friendly, but it was widely mistaken for a change in university policy. Some of the press coverage imagined that "he" and "she" were being outlawed. One opinion column even used the headline "New pronouns for the traveling freak show". State and federal lawmakers complained to the university, and the post was removed the following week.

It's not just in US universities that gender-neutral language is advancing. Last year, Facebook gave users the option to customise gender beyond male and female, and pick a pronoun from "he", "she", and "they". This summer the Oxford Dictionaries website added the honorific "Mx", defining it as "a title used before a person's surname or full name by those who wish to avoid specifying their gender or by those who prefer not to identify themselves as male or female". Meanwhile, Caitlyn Jenner and the controversy over Benedict Cumberbatch playing a non-binary character in the film Zoolander 2 have kept the subject of gender identity topical.

Universities, however, remain the most fertile ground for new pronouns.

kat baus, a non-binary student who graduated from Harvard this year - and who also writes their name without capital letters - regrets that the university's computer system was not introduced earlier. "It would have been a lot easier and less awkward," baus says.

baus sent emails or visited professors during office hours to explain their gender identity and pronouns. In smaller classes they (baus) brought it up when introducing themself.

"I don't know a single trans person who likes having that conversation," baus says.

Being able to do it with the click of a mouse would have allowed them to get straight down to their work in class, baus says - and would have allowed their classmates to get straight down to theirs.

Pronoun panic

It is sometimes difficult to determine somebody's gender by sight but what if you're blind? Mike Lambert recently experienced this problem when he attended a course on equality and diversity.

"I listen hard to Nina's voice. There's something soft and tentative about it - but the pitch is unmistakeably male... I tell myself that any concerns I have about Nina's gender are a thing of little consequence. The whole point of the day is equality and diversity, and I shouldn't get so hung-up trying to slot people into neat pigeon-holes. And then, I'm struck by a horrifying thought. How am I going to get through more than a couple of sentences without committing myself to 'he' or 'she', 'his' or 'hers'?"

Identifying gender when you're blind

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.