The fear of being Muslim in North America

- Published

Shia Muslims protest IS in front of the White House

After terror attacks in Paris and California, Muslims in North America are facing a sometimes violent backlash.

Omar Suleiman, a resident scholar at the Valley Ranch Islamic Center in Irving, Texas, was out of the country when he got word from his wife that their home address had just been published, external along with dozens of others by an anti-Islamic organisation.

The group, which had just held an armed protest, external outside the Islamic Center of Irving, got Suleiman's address because he registered to speak at a city council meeting back in March. He was asking the city council not to support a state bill , externalthat many in the Muslim community viewed as anti-Islamic.

Now, the address of the home he shares with his wife and two young children was all over the internet. Suleiman cut the trip short and flew back. Even though the list was eventually removed from the web, Suleiman and his wife were terrified.

"Hundreds of thousands of Islamophobes have our home address," he says. "It was a means of intimidation."

Anti-Muslim rhetoric is nothing new in North America. It was rampant in the Canadian election, when incumbent prime minister Stephen Harper made eliminating the niqab at naturalisation ceremonies a cornerstone of his campaign. It was also a factor long bubbling under the surface of the US presidential election - a poll in September found that one-third, external of Iowan Republicans think Islam should be outlawed.

But in the aftermath of terror attacks in Paris and in San Bernardino, California, anti-Islamic speech has risen to the surface of American political discourse, as evidenced by the latest proposal by presidential candidate Donald Trump that would bar any Muslim from entering the US.

"Our country cannot be the victims of horrendous attacks by people who believe only in jihad," wrote Trump, external in a press release.

Michigan town with majority-Muslim council

While Trump has no power to enact such a ban, Muslims living in Canada and the US say his words and anti-Islamic rhetoric in general have a real impact on daily life.

"I've been doing this for decades and I've never seen this level of fear in the American Muslim community," says Ibrahim Hooper, national communications director for the Council on American-Islamic Relations. "People are really wondering what's going to happen to them."

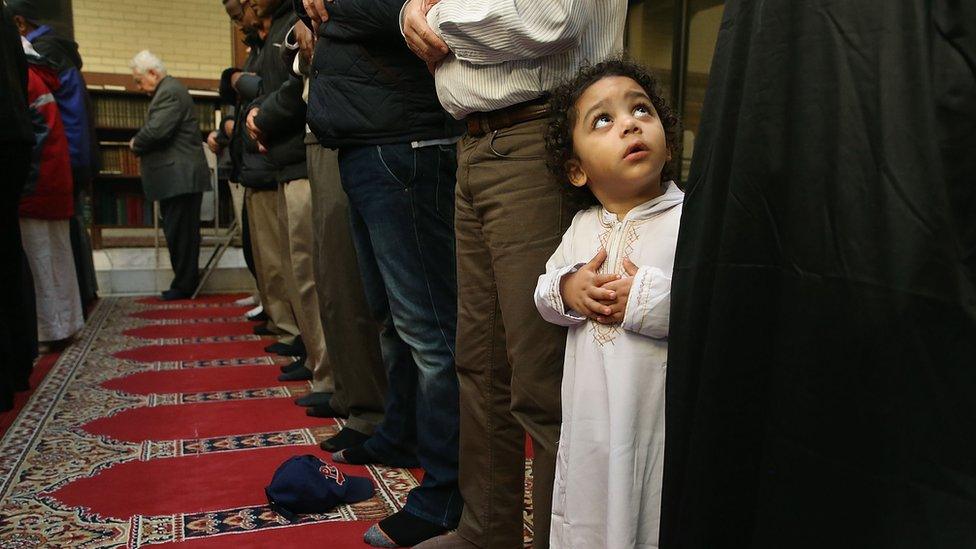

Some mosques have actually hired security guards or recruited volunteers to keep a watchful eye on the doors and parking lot. But as a religious centre that is supposed to welcome everyone, these measures can only go so far.

Umar Lee, a professional expediter who is often on the road, goes to prayers at the local mosque in whatever city he happens to be in. He says for the first time, he's being asked to stand up and introduce himself to the rest of the congregation.

"I've never seen that at a mosque before and I've been to hundreds," he says.

There is also particular concern for Muslim women, who are more easily identified if they wear a hijab or niqab that covers the head.

In New York, a sixth grade girl was attacked on the playground and called a member of the Islamic State for wearing a hijab, external. One woman in Toronto was called a terrorist,, external punched in the stomach and face, and her hijab was wrenched off her head. Another woman, external in Toronto was violently shoved against a wall and told to go back to her country, even though she was not Muslim and was wearing a scarf over her ears because of the cold.

The attacks inspired the online movement #JeSuisHijabi, external, which encourages non-Muslim women to try on a hijab and meet in public spaces to talk about the meaning behind the headscarves.

"In trying times like these it is certainly more difficult to wear the hijab. With that said, are Canadian women going to stop wearing the hijab because of this? No," says Hena Malik, spokeswoman for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama`at, which started the campaign. "They're loyal to their country. They're certainly going to speak loudly against terrorism."

Muslims across the US and Canada say that anxiety in the community often starts on social media. One person shares a story of being spat on, cursed at, or even assaulted, and fear spreads.

Lee says he thinks that vigilance is important, but worries that mass hysteria could prevent Muslims from practising their religion.

"When you scare people away from going to the mosque and participating in the lives of the Muslim community you can spiritually harm people. You have people on the edge - they had a hardship or they're just returning to Islam... they really need Islam in their lives in that time," he says. "To scare that person is irresponsible."

Suleiman heard from so many men afraid to pray openly and women asking if it was alright to cover their headscarves with a hoodie or cap that he put out a video on YouTube, external to assure them from a scholarly perspective that removing the headscarf or skipping prayers is alright if they fear for their safety. But he also wanted to offer words of support and galvanise the Muslim community in Texas.

"It's important for Muslim men and Muslim women to maintain a strong identity," he says. "We can't let fear dictate our faith. We have to show resilience."

At the same time, he was dismayed to hear that yet another rally is being planned outside of the Irving mosque, this one is organised by the Klu Klux Klan, external.

"To hear the KKK is still around and organising something - it really, really, really just was a huge wake up call as to how far we're regressing with the rhetoric," he says.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.