A Christmas Carol: What was it that upset Charles Dickens?

- Published

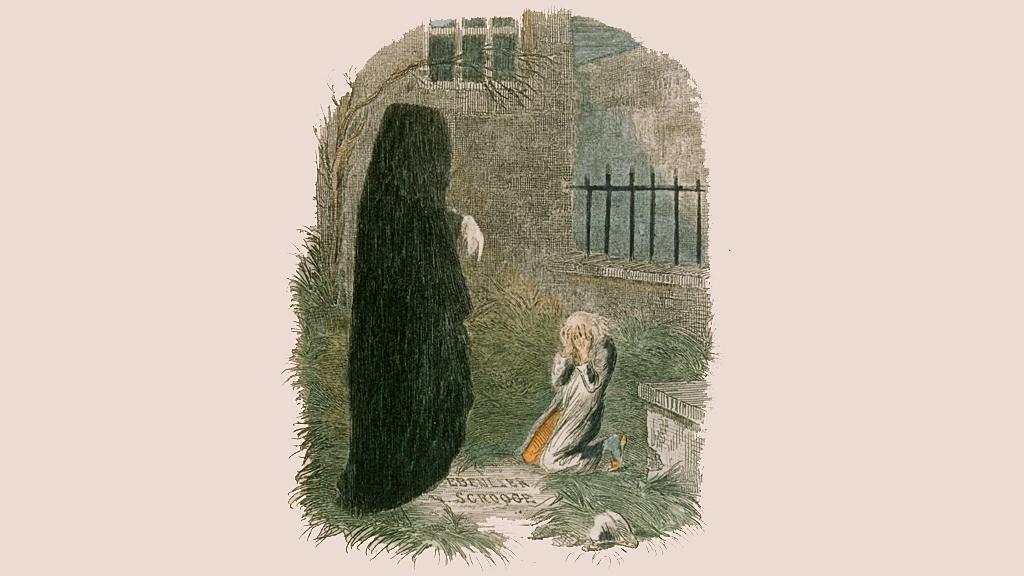

Jacob Marley's ghost appears before Ebenezer Scrooge

How does one small book - published six days before Christmas 1843 - still manage to capture the spirit of the festive season? Travel to Charles Dickens's first family home in London to see why A Christmas Carol endures.

"Bah, humbug," say people who struggle to get into the festive spirit.

And the Christmas killjoys are, of course, echoing Charles Dickens's miserly creation Ebenezer Scrooge.

"A Christmas Carol is such an accessible tale," says Louisa Price, curator of the Charles Dickens Museum, external in central London.

Scrooge is visited by the ghost of his former business partner, Jacob Marley - and then by the three Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come. They point out to him the error of his ways, and how Christmas should be a time of goodwill and cheer.

"Mr Fezziwig's Ball" - by John Leech, from A Christmas Carol

"It crystallises some of the things we really love and celebrate over the season," says Price. "It could even pull you away from 21st Century consumerism."

The Charles Dickens Museum is at 48 Doughty Street in Bloomsbury - which was home to the author and his young family for over two years from 1837.

Doughty St looking north, circa 1900

He established himself as a successful author in the house, completing The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist there - writing Nicholas Nickleby in its entirety - and starting work on Barnaby Rudge.

"This really was the house where he proved himself as a prolific writer," says Price.

48 Doughty St, present day

Dickens did not write A Christmas Carol within its walls, but Price stresses the author's love of this time of year.

It's something which she feels helped him tell such a compelling tale when he did eventually put pen to paper.

The museum is decorated for Christmas 1837 - Queen Victoria's first on the throne.

There are evergreen hues - holly, ivy and mistletoe. And the dining table is ready to welcome guests.

Dining table at 48 Doughty St laid for Christmas Dinner

Dining table at 48 Doughty St laid for Christmas Dinner

"Irrespective of his poor upbringing, Dickens really loved Christmas," says Price.

As a child, his father loved to put on theatre pieces for the family - and one of his old school teachers was known for his 12th Night parties in early January, with dancing and cake.

Nursery at 48 Doughty St, ready for a party on 12th Night

"Dickens grew up with all these traditions - and they continued as he brought up his own family."

Dickens was also known for his conjuring skills - and used to dress up as a magician to perform for his children and party guests.

Dickens Invoking the Spirit of Christmas - from a drawing by Kyd

But why - with all the festive fun at home - did he decide to tell the story of a mean-hearted man called Scrooge, who needed to be taken on a path of redemption?

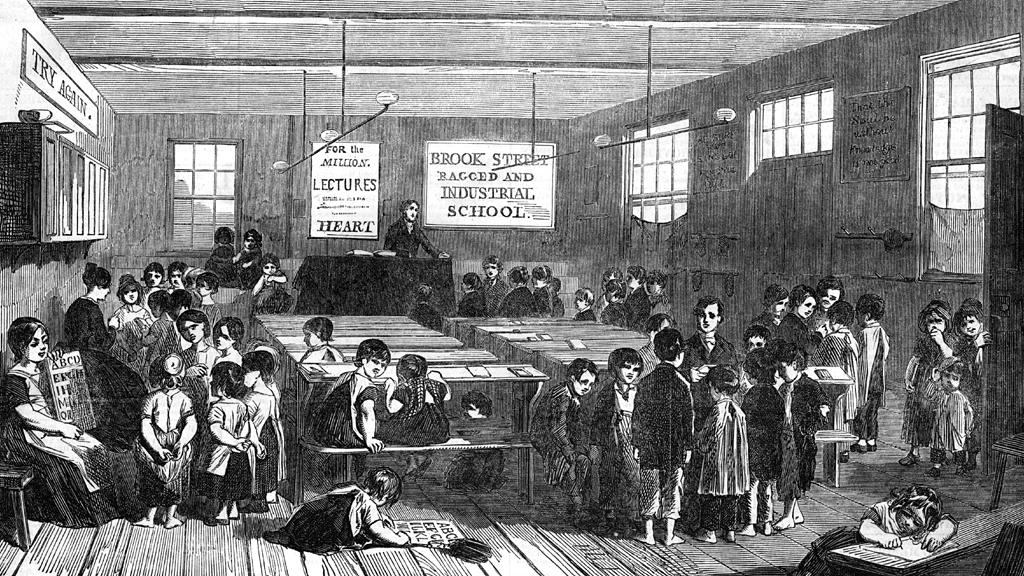

Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in the autumn of 1843, a year which saw the publication of a government report which highlighted plight of child labour.

"Dickens was incensed by its findings," says Price.

During the year, on a visit to his sister in Manchester, he also met charities supporting the working poor. And he went to see conditions at one of London's Ragged Schools - set up with the aim of educating destitute youngsters.

Depiction of Brook Street Ragged and Industrial School, 1846 (Illustrated London News)

Price says Dickens was so angered by the government report that he had initially planned to raise the issue by writing a political pamphlet - drawing on his past experience as a political reporter.

But then he changed his mind.

"He wrote to a friend," says Price, "saying that he would instead publish something at Christmas which would have 20 times the force."

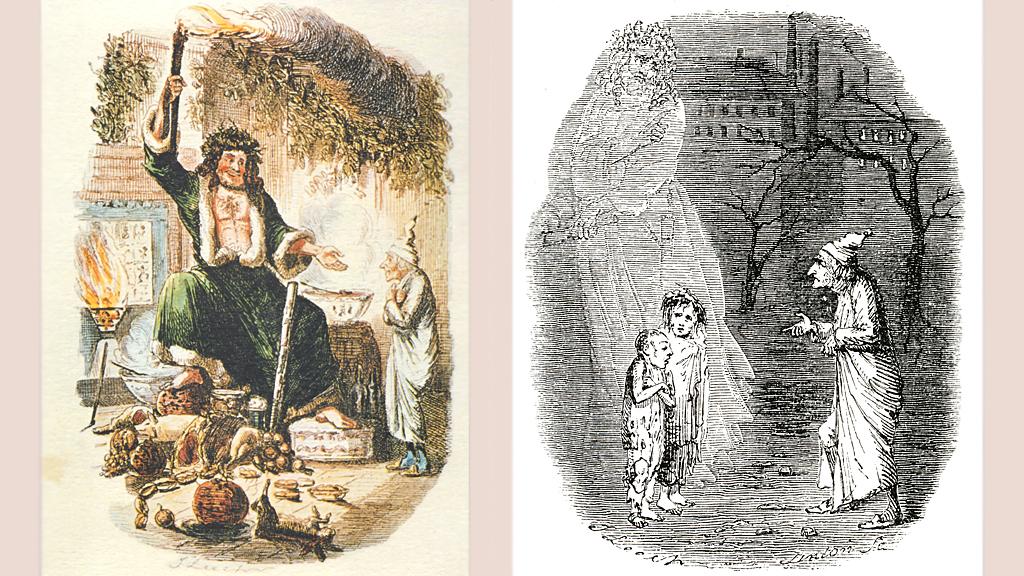

"The Second of The Three Spirits" or "Scrooge's third Visitor" and "Ignorance and Want" - by John Leech

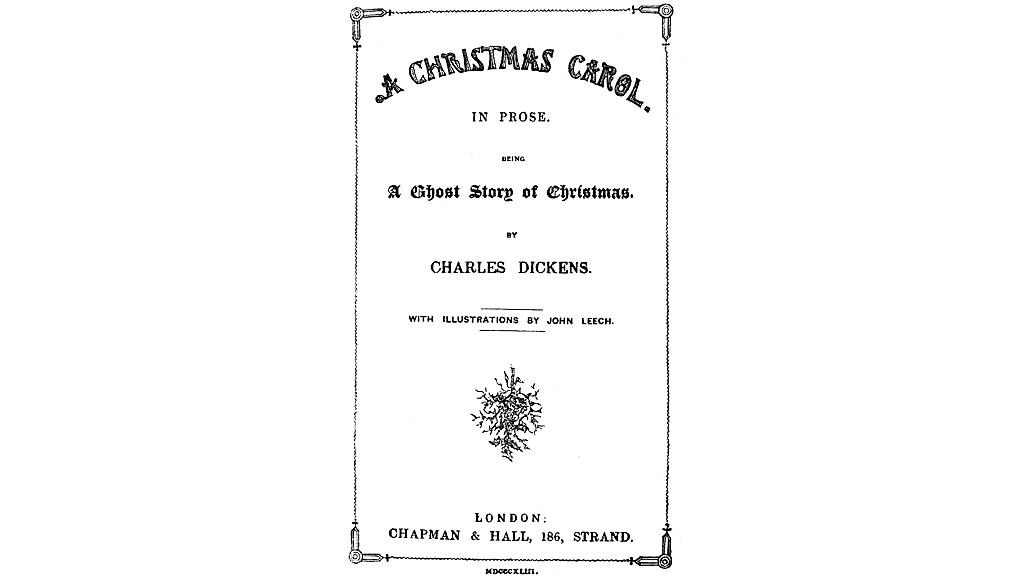

Dickens wanted A Christmas Carol to be a high-quality publication. The initial print run had a cinnamon cloth binding, with gold detail on the front.

Inside there were eight illustrations by the caricaturist John Leech.

"The Last of the Spirits" - by John Leech

Dickens's strategy worked.

Released six days before Christmas 1843, all 6,000 copies were sold by Christmas Eve.

"Dickens was on a wave," says Price.

"And at that time of year there was a tradition of telling ghost stories. Communities would gather to welcome in Christmas around the fire, and Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol knowing it would be read aloud."

"Scrooge and Bob Cratchit" or "The Christmas Bowl" - by John Leech

But as the novella has been adapted and re-versioned for modern audiences, says Price, the haunting elements of Dickens's original story have often been diluted.

And so it was refreshing, she says, to see darker elements from the book return in new visual interpretations of the tale - commissioned by the Dickens Museum from students at Central St Martins at the University of the Arts London.

"Shackled Ghost"

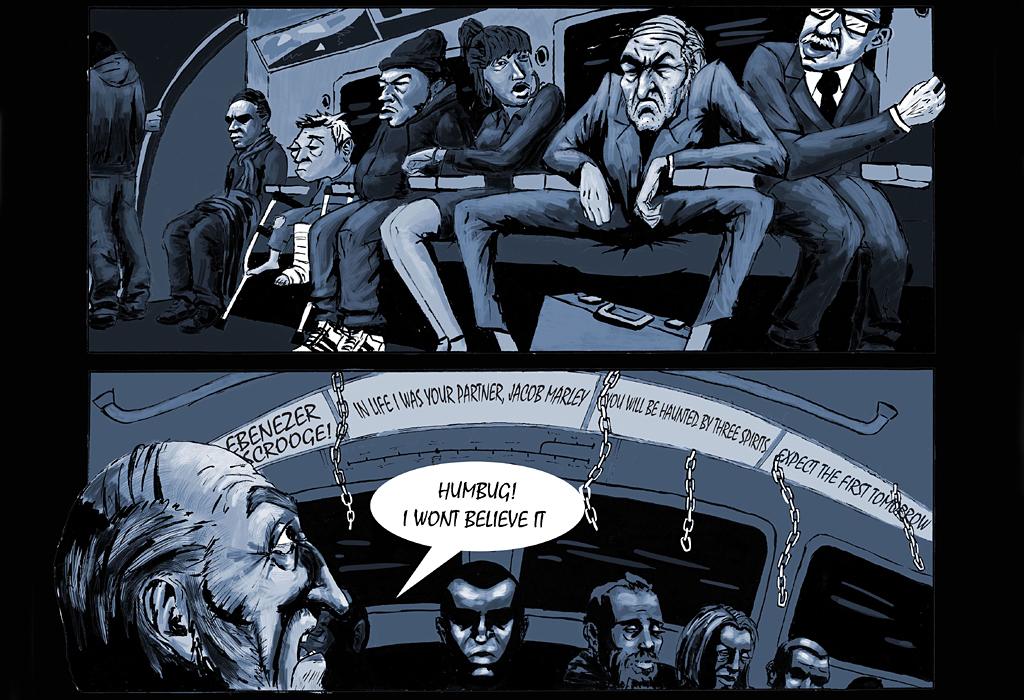

This comic strip tells A Christmas Carol as a graphic novel - putting Scrooge in a modern day context.

He is "manspreading" on the London Underground, taking up more leg room than he should.

"A Christmas Carol the comic" (detail)

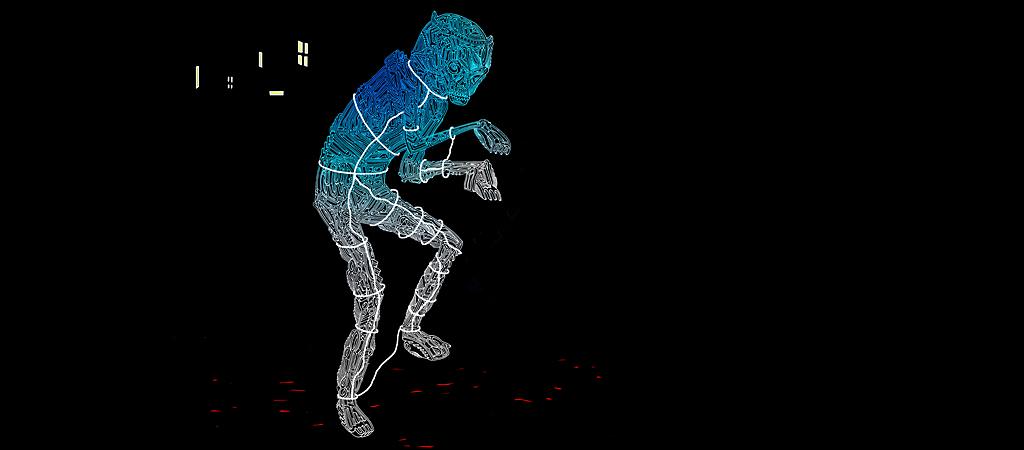

Another student picked up on Dickens's ghostly elements, but also took inspiration from 1950s horror film posters.

"1950s Christmas Carol B Movie Posters"

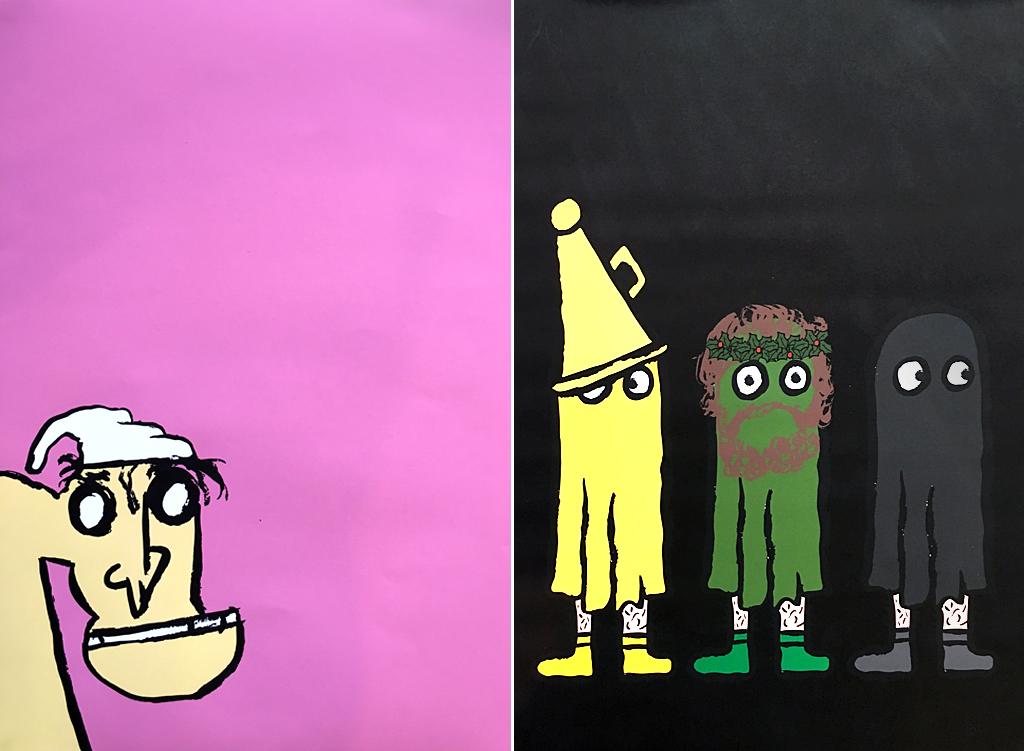

Set against a bright pink background, this Scrooge is just a grumpy old man. The artist has reduced all the key details of A Christmas Carol to the most basic elements.

"Scrooge" and "3 spirits"

Price says some of the students had not read the book before, and that probably helped them reinterpret the story - linking them to 21st Century issues, like homelessness and the refugee crisis.

"The Story from the Perspective of Today"

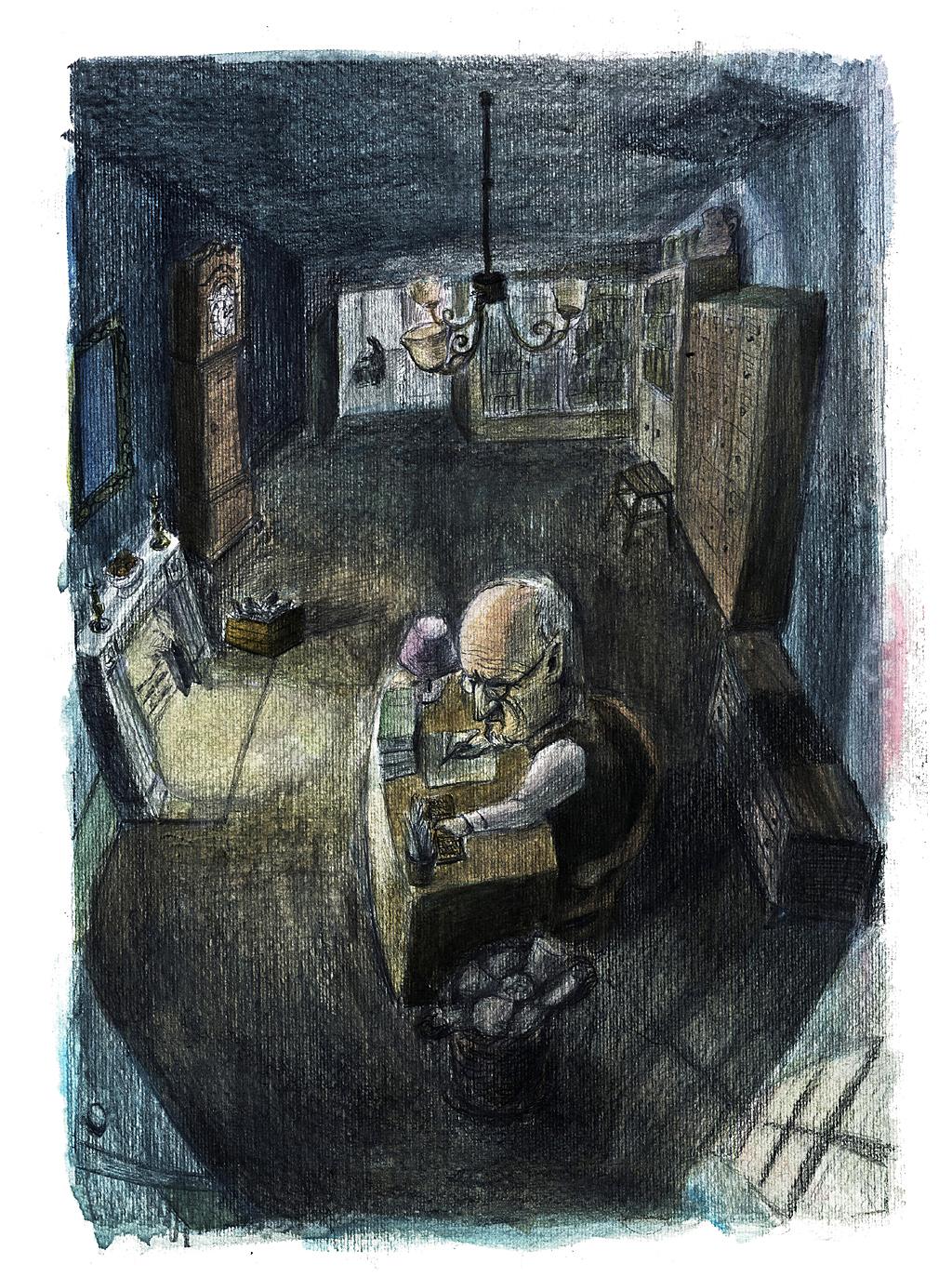

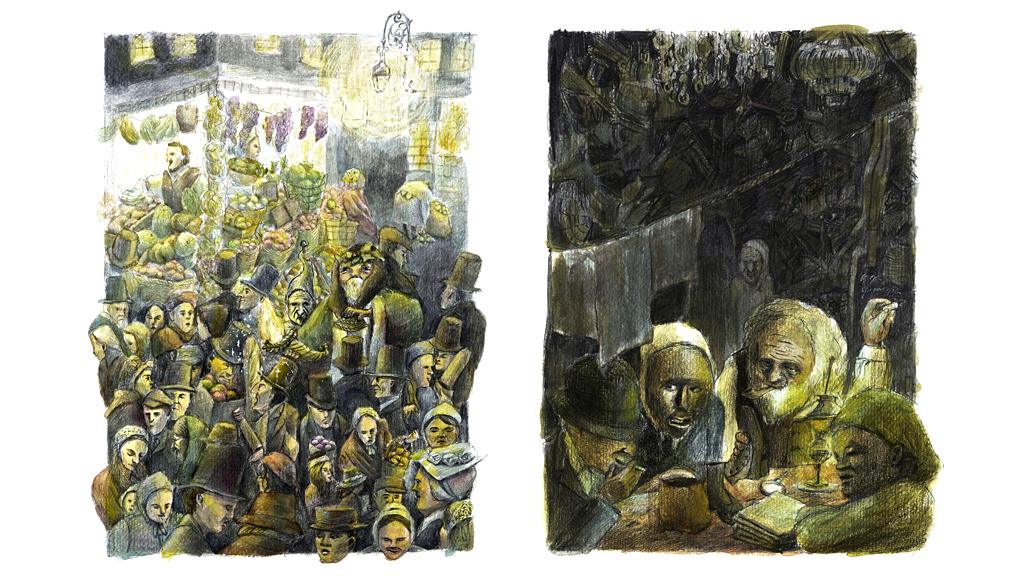

The next set of three images won the museum's competition.

"What the judges loved about this work was that they make a real nod back to the original illustrations by John Leech," says Price.

"Scrooge's iced office"

"They could very easily be scenes from Dickensian London, but are also recognisable to a 21st Century audience too."

"It's a shame to quarrel" and "The horrifying dialogue"

"One of the reasons A Christmas Carol has stayed with us for so long is because it buys into our love of colourful and elaborate storytelling at Christmastime," she concludes.

"Dickens knew how to captivate an audience. Throughout his life there were people who urged him to get into politics - but he resisted.

"What he knew was that his influence was far greater as a literary figure. And that is why so many of his stories are infused with his moral and political views."

The Charles Dickens Museum, external will be dressed for Christmas - with the art from the Central St Martins students on show - until 6 January 2016.