Adele: The full story

- Published

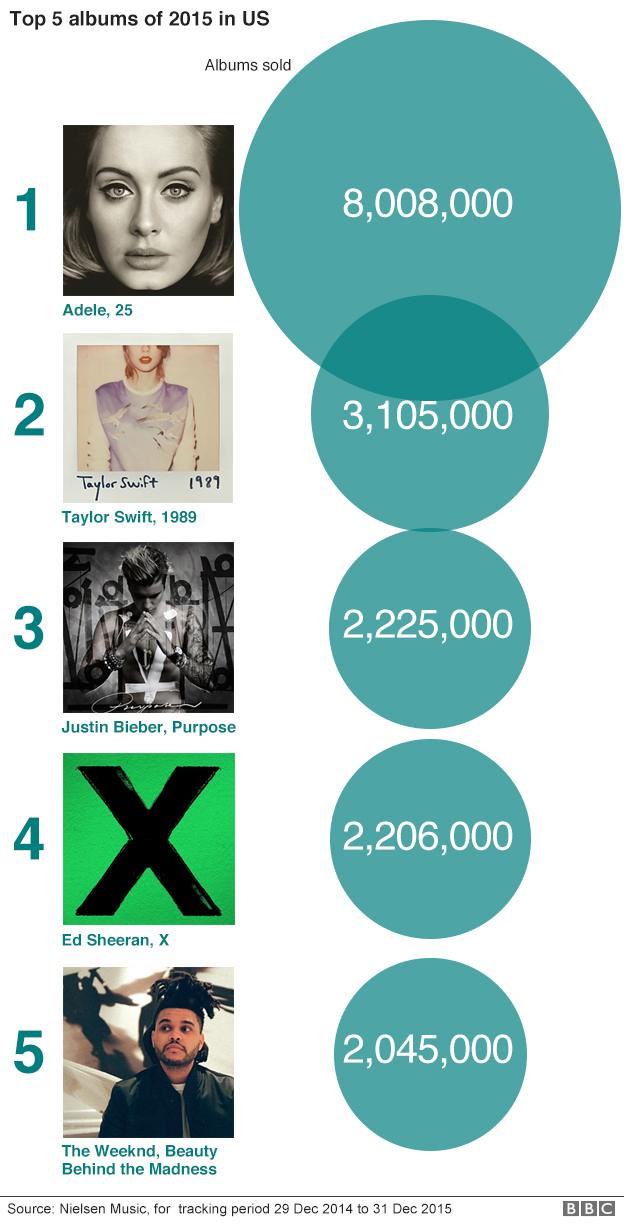

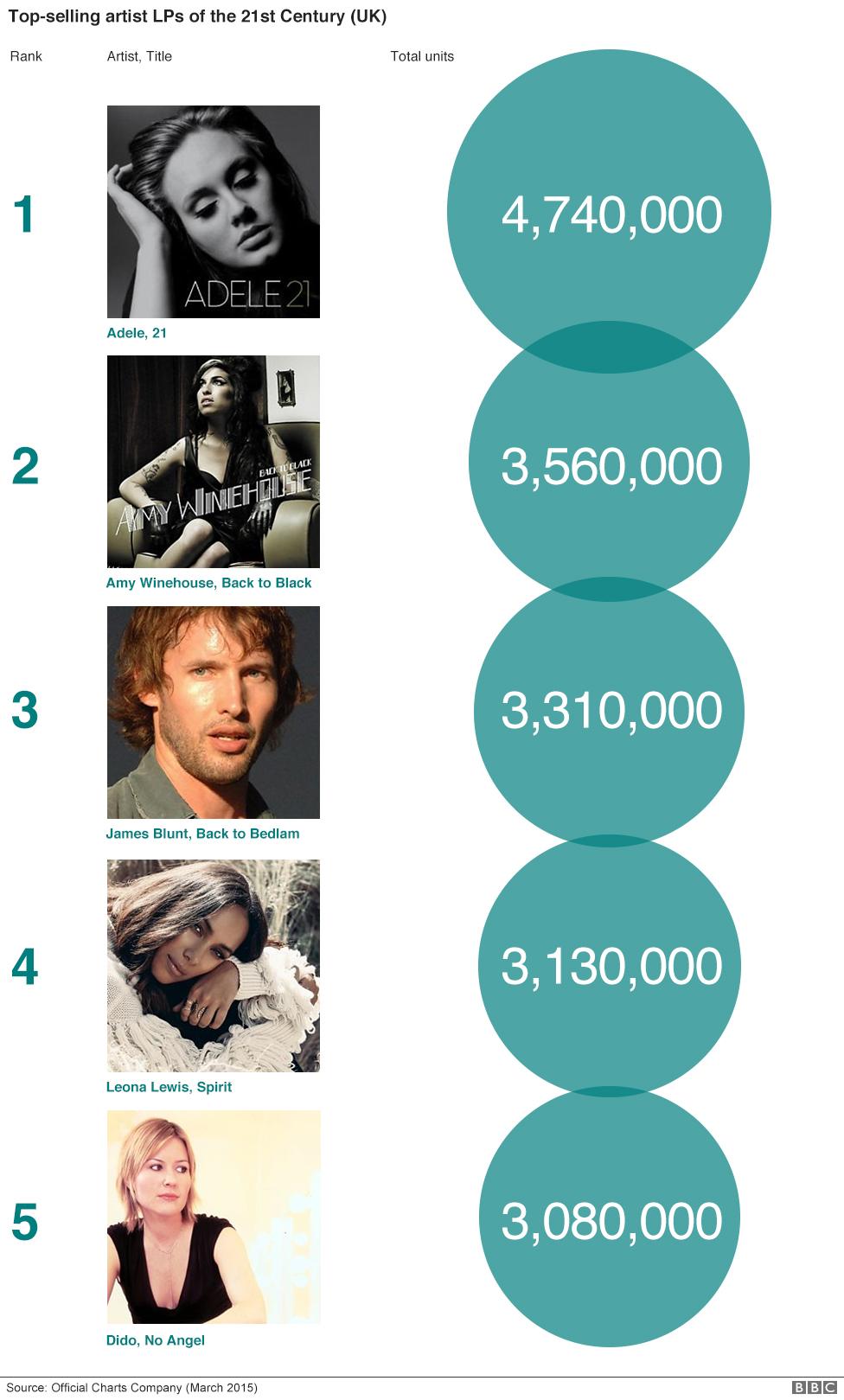

In little more than eight years, Adele has come from nowhere to establish herself as one of the world's biggest entertainment brands, right up there with Grand Theft Auto, Star Wars, FIFA 2016, and Call of Duty. The proof was in the prizes on Wednesday night, when she walked away with a record-equalling four Brit Awards. Her success is a remarkable achievement - all the more impressive given that she is operating in a market that has roughly halved in size over the past decade.

It is a feat for which she has been been lauded, applauded and awarded across the globe. And called a "freak", by Tim Ingham, the respected music journalist who runs the website Music Business Worldwide. She is not normal, he told me. At least, in terms of her achievements: "Breaking album sales records in 2016 is in and of itself a miracle." That is a sentiment echoed by a high-ranking music exec who preferred not to be named. He called Adele "an anomaly", "label-proof", and a beacon "of hope for the industry".

For a beleaguered and besieged music business Adele is living proof that money can still be made in an industry dominated and decimated by streaming and freeness. The bad news, according to Ingham, is that Adele is "the artist you cannot manufacture". She's a one-off. Which was apparent from the start.

Adele was the big winner at the 2016 Brits with four awards

There is a slightly irritating but quite enlightening lo-fi video you can watch of Adele Adkins online, external. It was recorded in the back of an Airstream caravan as part of Pete Townshend's In The Attic series of webcasts, which were usually made around the time of a Who show. This particular edition was filmed in late May 2007, just before Adele got famous.

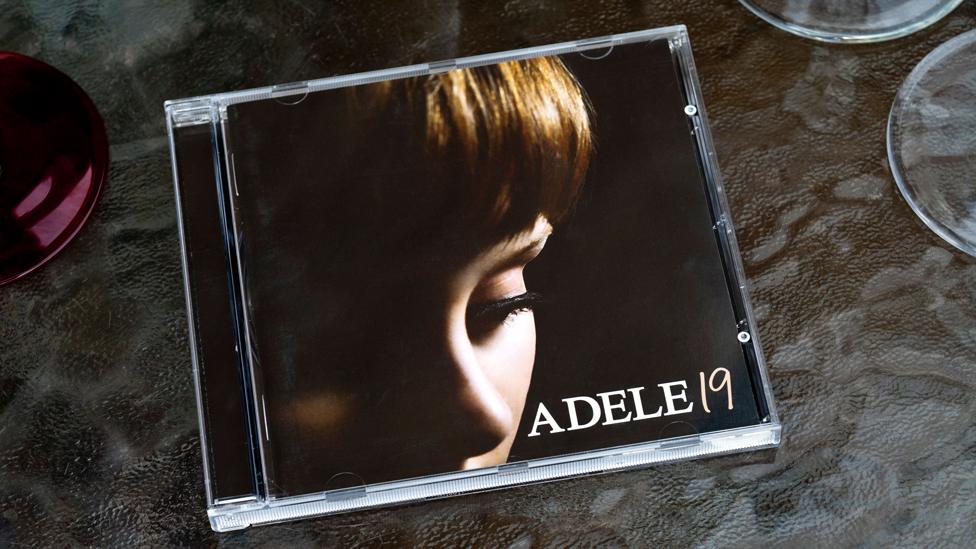

She had turned 19 a couple of weeks earlier and was still working on her first album (eventually released in January 2008 and called 19 after her age). Townshend's partner, the musician Rachel Fuller, plays the Chat Show Host. She and Adele sit side-by-side in the foreground on faux Louis XIV chairs, Townshend and songwriter Mikey Cuthbert are squeezed in at the back.

The interview aims at a Tiswas/TFI Friday informality and irreverence. It misses. But it is telling, nevertheless. We learn a lot. There are the basics: Adele was born in Tottenham, North London. Around the age of 10 she moved to South London (Brixton, then West Norwood). She didn't enjoy school until she was 14 years old. That was when she accepted an offer to attend the selective, state-sponsored Brit School for Performing Arts & Technology in Croydon. There she thrived. Her dad - of whom more later - bought her the Simon & Patrick guitar she plays in the video, an instrument she says she'd only taken up 18 months earlier. By then she'd cracked playing the sax, having given up the flute at 13 because she'd started smoking.

Adele in 2007 - an assured stage presence from the start of her career

There's plenty more bio-type info to pick over, but that's not what makes this homespun tape an ace in Adele's archive pack. It's her performance as an ingenue interviewee and singer. In both guises she is conspicuously composed and self-assured. So much so she makes her hosts look like the wannabes. It is apparent even at this very early stage of her career that Adele knew what she was about.

She is neither star-struck by Townshend's presence nor impressed by Fuller's overbearing style. She goes along with the banter enough to ensure she doesn't appear rude or arrogant, but makes it obvious she thinks the conversation is a bit silly. She comes across as an independently minded, matter-of-fact alpha-female who is comfortable in her own skin.

She has since been variously described as fun, gobby, bolshie, and loud - a big personality who (and this comes up less frequently) is not one to suffer fools. I have heard that a lot. Not publicly though. "Off the record" was a standard refrain used by industry-types when speaking to me about her. They were worried about upsetting the singer, which is not surprising. She is a powerful individual who can make people nervous. My guess is that has always been the case. Adele Adkins is a force to be reckoned with. As is her voice.

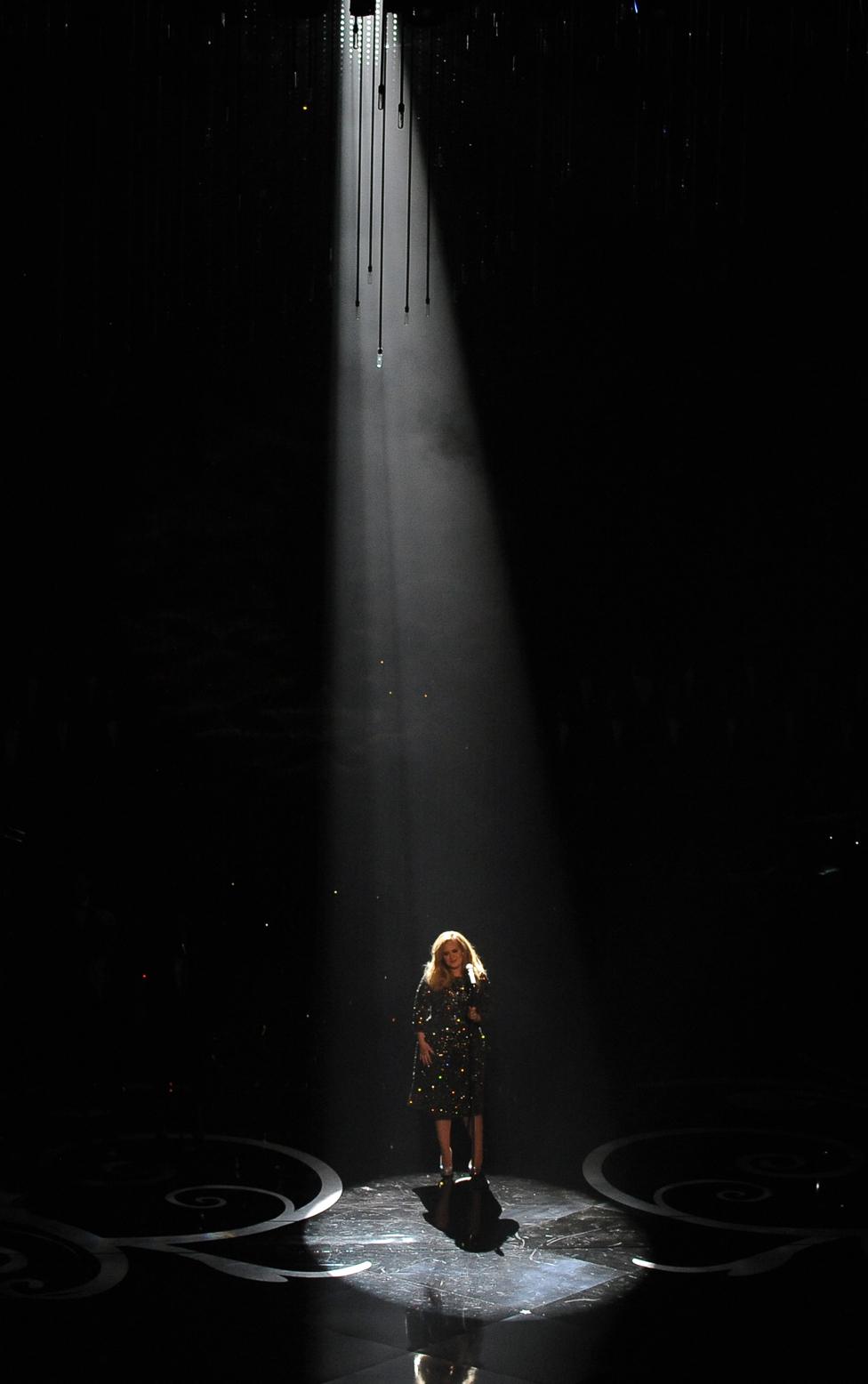

Adele performing at the 2016 Grammy awards

Notwithstanding the technical mishaps of her recent Grammy performance where she described her singing as "pitchy", there is no doubt she is blessed with a remarkable voice. Hearing it live is something else. I remember being in the O2 Arena in London one afternoon back in 2012. I was on my own save for seven or eight events staff preparing tables for that night's Brit Awards. I was standing at the end of the runway stage when Adele walked on from the wings with three or four backing singers, tapped a microphone, signalled to the sound desk, and let rip with Rolling in the Deep.

Her voice filled the arena, its natural ampage sufficiently voluminous to make the great hall feel like an intimate nightclub - a sensation heightened by the raw emotion she conveyed in the song. She had already demonstrated this ability to the thousands gathered in the same venue a year earlier for the 2011 Brit Awards where she gave a career-defining, reputation-sealing, sceptic-crushing performance that was witnessed by millions watching live on television and subsequently hundreds of millions catching up online.

She sang track 11 - Someone Like You - from her then recently released album, 21. Some of the other acts that night had been unbelievable, wowing the audience with their fancy routines and stunning stage sets. Not Adele. She was not unbelievable at all. She was much better than that. She was totally believable. Many an eye welled as she sang her painful lament with heartrending candour.

From a production point of view, it was a pared down piece of showbiz perfection. The attention to detail was forensic, the presentation as slick as a diplomat's dinner party. Adele, for her part, gave a masterclass in the art of method acting. She has the emotional dexterity of a leading lady, shifting seamlessly between time and place, drawing on past experiences, conjuring up the associated feelings, and then unbelievably believably reliving them in the present.

Performing at the 2012 Brit awards

But for her to do so, the scene has to be appropriately set. There is no place for the spectacular pyrotechnics on which other performers rely. Simplicity is all - no distractions, no safety net. She is playing the solo artist in every sense, vulnerable but defiant.

Hence we see her standing apart on a bare stage in the cavernous O2. The scale of the physical space mattered. There she was, alone and exposed like a Bronte heroine in the landscape. Away to her right was a grand piano at which a silent man in a dark suit and a pair of shades sat. A single spotlight framed Adele, making her earrings sparkle and golden hair glow. The mood of sombre isolation was accentuated by her black dress. The look was minimalistic and monochromatic, the message clear: This is special, it is for you, pay attention.

It worked. When she finished the room erupted in vigorous applause. Adele stepped away from the microphone and looked at her feet. Emotions were running high, hers included. That was down to the lyrics, which hark back to the end of a relationship with a man 10 years her senior who - she had recently discovered - had become engaged to someone else. As her mezzo-contralto voice had sung out the words she had started to picture her ex-lover watching the telly and laughing at her inability to get over him.

There are many artists - Nina Simone comes to mind - who can communicate love and loss with staggering authenticity in songs written by others. Not so much Adele. With the exception of her version of Bob Dylan's Make You Feel My Love, she is much, much better when performing her own songs, where her investment in the narrative is palpable and persuasive.

Nothing distracts from the vocal performance on stage

Her approach to writing typically involves her hand taking direct instruction from her broken heart - sometimes in the form of a "drunk diary" - and then, more often than not, being honed with an established lyricist such as Eg White, Paul Epworth, or Ryan Tedder. The idea is to make them as "personal as possible", according to Dan Wilson, co-writer of Someone Like You.

Frank honesty is her trademark, her shtick. It's her default public persona on stage and off - the whole what-you-see-is-what-you-get thing, complete with cackles, vulgarities, and informal chattiness. It's charming, in the same way as being polite to your friend's parents is charming. In reality there is absolutely nothing easygoing or flippant about the way Adele controls her public image. Her "brand" is micro-managed with the same meticulous professionalism she brings to her music. In the fame game you have a choice - manipulate or be manipulated. She has chosen the former.

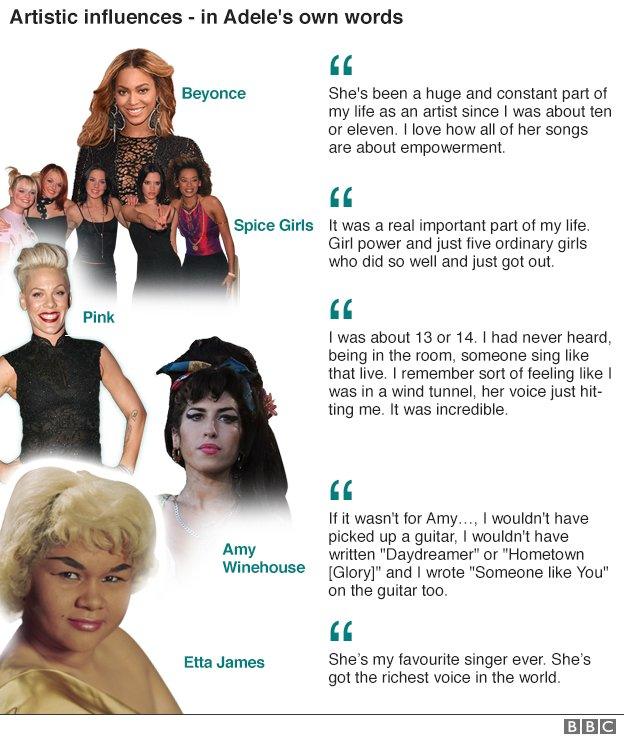

Adele in her own words

"When Twitter first came out, I was drunk-tweeting and nearly put my foot in quite a few times. So my management decided that you have to go through two people, and then it has to be signed off by someone." (BBC, 2015)

"I don't make music for eyes, I make music for ears." (Rolling Stone, 2011)

"I get so nervous on stage I can't help but talk. I try. I try telling my brain: stop sending words to the mouth. But I get nervous and turn into my grandma." (Observer, 2011)

"I love a bit of drama. That's a bad thing. I can flip really quickly." (US Vogue, 2012)

When stories started to leak out about her in the press a few years ago, her suspicious mind turned towards members of her inner circle. She devised a mischievous plan to test the loyalty of her subjects and flush out the treacherous. She instigated a series of private tete a tetes with individuals in her court into which she would drop a juicy piece of bespoke insider information. With the trap thus laid, she would sit back and wait to see which, if any, of her planted tidbits found their way into the public domain. If and when they did - and they did - the culprit(s) would be swiftly excommunicated ("I get rid of them"), a process she described as "quite fun".

It did the trick. The leaks dried up. The frighteners had been put on. But the message hadn't reached Wales, where her estranged father Mark Evans was living. He gave chapter and verse to the Sun in 2011, with further quotes appearing in the Daily Mail. He told how he met Adele's mother, Penny Adkins, in a North London pub in 1987 when he was in his mid-20s and she was a teenage art student. They moved in together, she soon fell pregnant, and Adele Laurie Blue Adkins was born on 5 May 1988.

He didn't hang around. He went back to Wales, worked as a plumber and became an alcoholic. Penny moved to South London with their daughter and worked as a masseuse, furniture maker and office administrator. He speculated that Adele's music was "rooted in the very dark places she went through as a young girl", citing his departure and the death of his father, to whom he said his daughter was very close. He hoped that after years of separation from Adele they could patch things up. Adele's response to her dad's tabloid tales was unequivocal: "He's f***ing blown it. He'll never hear from me again… If I ever see him I will spit in his face."

Her father said it was he who imbued his daughter with a love of music. She talks about her mother listening to Jeff Buckley and taking her to gigs - The Beautiful South when she was three years old, The Cure a couple of years later. By the age of 10 she was making her own choices, with The Spice Girls her No 1: "It was a huge moment in my life when they came out. It was girl power. It was five ordinary girls who did so well and just got out. I was like, I want to get out."

Adele gives a tour round her favourite pub in 2008.

She did. She left her comprehensive school in Balham, where she said there was a depressing lack of ambition, and went to the Brit School - Amy Winehouse's alma mater. She met her best friend Laura Dockrill (now an author and performance poet), about whom she wrote the song My Same (they had a big falling-out, then made up. Adele says she likes to create drama).

Her guitarist Ben Thomas went there too, watching Adele get in to trouble for sleeping in and turning up late. But she was there promptly for at least one morning assembly where she sang a song that impressed Stuart Worden, now the headmaster, so much he asked if he could have a copy. "Well…" she said. "You'll have to buy it."

That's the thing about the Brit School. It teaches its students (Mr Worden calls them artists) the business behind the show, which has benefited Adele. She likes a good deal. Like the time back then when she went into a record shop and bought two albums for £5, one by Ella Fitzgerald, the other by Etta James. She didn't actually know who they were, she just wanted to look cool. But she listened to them. Eventually. And was inspired (she frequently name-checks Etta James as an influence). She wrote some songs and a friend posted them on MySpace. It was the summer of 2006.

Some context. Amy Winehouse had already become a big deal by this time. Lily Allen was making a splash with her first album Alright, Still. Ergo, feisty young women from London who could sing about their love lives were proving good for business. Music execs were on high alert to find the new Amy/Lily. MySpace was the default page on their computers.

A producer at a hip indie record label called XL heard Adele's demo and gave a heads-up to Jonathan Dickins, a young, thrusting, recently established talent manager. Dickins met Adele. They got along. She knew he was the man for her plan. He took a little longer.

At this stage she had three songs. Dickins pointed her towards Dylan's Make You Feel My Love. Now she had four. He took her on and went back to XL. Richard Russell, the label's boss, signed her up even though her easy listening vibe (she called it acoustic soul) was not exactly true to his rave roots. The teenage girl who was into mainstream pop acts like Destiny's Child and Gabrielle was joining a roster that included the White Stripes and The Prodigy. It was now autumn 2006.

When she was at school scribbling down lyrics and coming up with melodies Adele was having fun. Now she wasn't. She felt under pressure. Professional people had invested time and money and belief in her, and she had writer's block. Months passed. She wasn't ready. Then she met a "horrible boy". He broke her heart. Bingo. A month or two later she was climbing into the back of Pete Townshend's trailer…

Jonathan Dickins - Adele's manager since 2006

She had her style nailed from the start - sit or stand and sing. No fuss. No bother. But then, she says she doesn't have rhythm, so dancing is out. Nor is she the athletic type with a Florence-like inclination to prance around the stage. There's not a band to interact with or Rihanna-style body to flaunt. She's just an ordinary girl with an extraordinary voice. So, er… flaunt that.

Which is what she has done, to great effect. She is perfectly imperfect. The ordinary girl thing works for her melancholic love songs - a universal theme to which the entire globe can relate. Her whole style seems so relaxed, so nonchalant. She can afford it to be. She has people covering her back.

Adele has built her very own A-Team - a formidable, mostly male, collection of world-class producers and managers, who keep her show on the road; a band of pipers paid to call her tune. Which is what you would expect given her position as the 21st Century's best-selling recording artist. More surprising, perhaps, is that her core crew has been with her from the very beginning. Which tells you something about Adele's story - it is largely about judgement not luck. She calls it right so often you'd have her pick your Lottery numbers.

There's Carl Fysh at Purple PR (who also looks after Beyonce, one of Adele's celebrity fans) managing her profile and avoiding the multiple elephant traps that are scattered across today's complex media landscape. And the aforementioned Richard Russell at XL, a creative collaborator who had the contacts and musical sensitivity to draft in the right talent to help her where and when she needed it, hiring producers of the calibre of Mark Ronson, Jim Abbiss, Brian Burton, and perhaps most notably, Rick Rubin, the celebrated, Svengali-like American co-founder of Def Jam Records. These were all good choices made by a savvy teenage Adele. But her best pick has to be Jonathan Dickins, her manager.

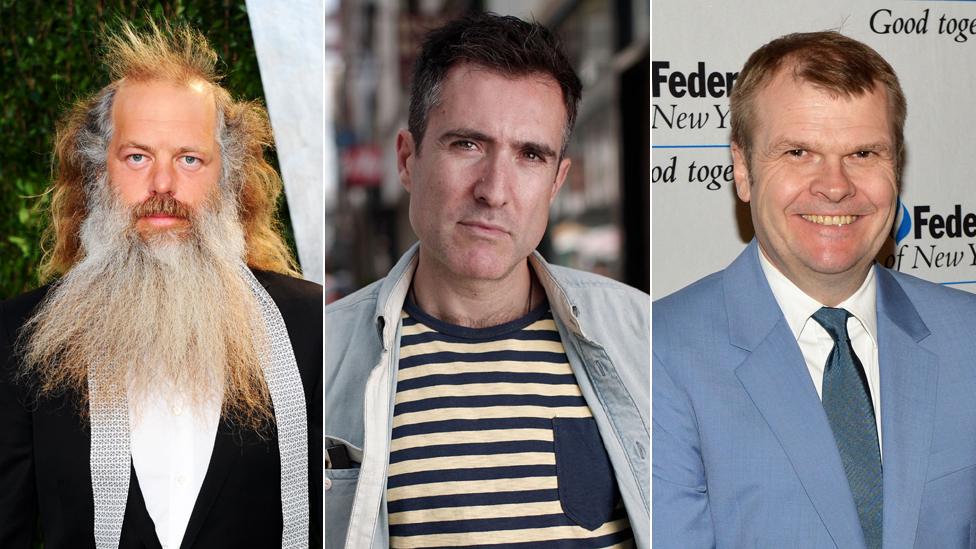

Team Adele

Rick Rubin (above, left) - co-producer of 21; founded Def Jam Records which launched hip-hop stars Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys; also produced Johnny Cash's final LPs

Richard Russell (above, centre) - owner of XL Recordings, Adele's UK label; other artists on his roster include Jamie XX, Damon Albarn and FKA twigs

Rob Stringer (above, right) - English-born chairman of Columbia Records, which releases Adele's records in the US

The fit appears to be perfect, the vision shared. They are in it for the long haul, they say. He jokes about the job being easy - all he has to do is spend 99% of his time saying no. Which is why you don't see the singer endorsing products, tipping up at celebrity openings, or rushing to get her next record out. Unlike her one-time rival Duffy - another British purveyor of "blue-eyed soul" - who was neck-and-neck with Adele for a while in the bestselling, Grammy-winning stakes, until she agreed to star in an awful commercial for Diet Coke in 2009, after which the wheels seemed to come off.

By contrast, Adele and Dickins - who also decided to get into bed with a multi-national consumer giant - didn't go down the route of providing a celebrity face for their corporate suitor. They did the opposite. The deal they did with Sony's Colombia Records was to use its reputation and clout to be the face of their product in America.

Being on the super-cool XL label in the UK worked. It set her apart from her major-label peers, and helpfully suggested her ostensibly commercial pop was tinged with an indie edge. But when it came to cracking the US market they needed something different, a partner with access to the all-important entertainment TV shows. XL could look after the rest of the world, but Rob Stringer at Columbia was going to be their man in America.

He didn't let them down. Columbia launched 19 in June 2008 with solid if unspectacular sales. But then Stringer got to work. He invited some execs from the high-profile satirical TV programme Saturday Night Live (SNL) to come and see one of Adele's shows. They liked it and booked her to be SNL's musical guest on 18 October 2008.

In what has now become a legendary episode in Adele's story, she ended up being on the same bill as the prominent Republican Sarah Palin, who had been invited at the last minute. That is the same Sarah Palin which SNL star-turn, Tina Fey, had down pat in a mocking caricature. The political/comic combo cranked up the viewing figures for the show by several million to a 14-year high. Fey came on and did her bit, Palin did hers, and then the director cut to the unknown and nervous young Londoner with a cherubic face and big green eyes that were partially concealed by a thick fringe of gingerish hair.

Adele was standing as still as a statue in a long shapeless black cardigan, gripping the mic stand as if she had vertigo. The piano, strings and snare drum struck up while the camera zoomed in and isolated the singer, a known sufferer of severe pre-performance nerves. She blinks… raises her chin… and storms it.

She softened them up with Chasing Pavements and then knocked them out with her Cold Shoulder. She was No 40 on iTunes before the show. When she woke up in the morning to prepare to fly home she was No 8. By the time she landed back in the UK she was No 1. Appearances on the David Letterman and Ellen DeGeneres shows followed, as did a frenzy of downloading and CD buying. Adele had cracked America.

Adele performs on Saturday Night Live in 2008

Or so she thought. In fact, as the subsequent record-breaking sales of her second album 21 would reveal, she had barely scratched the surface. The United States is a nation with an insatiable appetite for power ballads soulfully sung. Diana Ross, Whitney Houston, and Shania Twain are but three of the hundreds of talented female vocalists who have rolled off the US production line of ladies who can sell a love song. Adele can do that too, of course. But she has something others do not.

Like the way she pronounces her words when singing. It brings a freshness and energy to the gentle genre. Her inflections are the product of London's inner-city multicultural melting pot, which has morphed the traditional cockney diction into a one-size-fits-all urban patois. It's not an accent you're going to pick up in Nashville or Detroit. And then there's her vocal technique of riding the notes and chords like a super surfer in a high sea - effortlessly jumping octaves, applying her natural vibrato, changing pace, eliding words and verses, and modulating pitch. She uses this vocal dexterity like a lasso, to draw us in, to create a sense of intimacy, to turn the emotional dial all the way up to tear-jerking.

Her style is not everybody's cup of tea. Noel Gallagher "can't see what all the fuss is about". He doesn't like her music, thinks it's for "f***ing grannies" and is part of a "sea of cheese" washing over the rock'n'roll landscape. It is an idiosyncratic view but not an uncommon one. Nor is it altogether factually inaccurate.

What the critics said

Photo booth picture, 2007

"She may have a jazz musician's disdain for melody, but just listen to her informing a lover that he is a 'temporary fix' on 'Best For Last': 'You're just a filler in the space that happened to be free/ How dare you think you'd get away with trying to play me?' she huffs, a schoolgirl on the top deck of a bus nonchalantly channelling Aretha." The Observer, 2008

"Some will find Adele rigidly old-fashioned. Her influences (Etta James, Dusty Springfield, Billie Holiday) are from another age. Her music breaks less ground than a pneumatic drill made from plasticine. But she sings with unabashed passion about a kind of pain we can all recognise, and that sort of thing doesn't date." Daily Telegraph, 2008

"21, Adele's second album—named for her age at the time she began composing it—has a diva's stride and a diva's purpose. With a touch of sass and lots of grandeur, it's an often magical thing that insists on its importance." The Village Voice, 2011

A Nielsen survey undertaken in December 2015 shortly after her latest album 25 was released in America, found that a significant percentage of the "early adopters" buying the physical product were empty nesters aged 55-64 and most likely from high-income households. That's not the usual demographic for pop music.

Nor is Adele's overall American fan-base, which, according to Nielsen is female-skewed (62%), aged mostly between 25-44 years old, and with children. It is not known if that profile is mirrored around the world, but what is beyond contention is the size of her following. It is huge. When 25 was released in November it went straight to No 1 on iTunes in 110 countries. Moreover, it was the fastest-selling album of all time in the UK with 800,307 copies sold in its first week, beating the previous record holder (turn away now Noel), Oasis's 1997 album Be Here Now. It did even better in the US, obliterating any previous first-week album sales record with an historic 3.38 million units (or equivalent in aggregated downloaded tracks) shifted. This tidal wave of chart-topping sales covered countries and continents.

Adele appeared relieved. Thankful that the fan-base she had built up with her first two albums had retained an interest in her output even though she had kept them waiting nearly five years. A case of absence making the heart grow fonder, maybe. Anyway, she had been busy. She had fallen in love again, this time with an ex-public schoolboy 14 years older than her called Simon Konecki. They had a child called Angelo, whose name is tattooed along the outer edge of her right hand. She won an Oscar for singing the Bond theme for Skyfall, and picked up an MBE from the Queen.

Everything was going well, except for the songwriting. She had come up with some lyrics about being a mother, but Rick Rubin and Jonathan Dickins weren't impressed. Rubin said he didn't think they were authentic. Dickins suspected she was rushing. She thought they were right.

Adele with her partner Simon Konecki at Glastonbury 2015

She lost confidence, and felt guilty leaving her young son at home when she didn't really need to work. But artists are artists and they must make - they are necessarily selfish. She got frustrated. And then she had an idea. Both 19 and 21 had a narrative running through them. They were - in a way - like 1970s concept albums. That was part of the reason for her success. In an age when album sales are plummeting (the Wall Street Journal reports 785 million albums were sold in 2000 in America, compared with just 257 million in 2014) she is selling more than most of the big acts did back in the music business's glory days.

But what did she have to write about? There was no heartbreak to report. An album about how difficult it is to be very rich and very famous wasn't going to wash. And then the scales fell. The one thing she had loved and lost was her life, as she knew it. She was no longer that happy-go-lucky teenager from Tottenham who'd knock back bottles of cheap cider with her mates in the local park. She was an internationally respected artist, with a retinue of professional helpers, an Old Etonian for a partner, and a brand worth millions - if not billions. That self-assured teenager with a decent voice for karaoke, who was a bit of a face in her local manor, was long gone. She got writing.

Adele performs a song from her new LP

And all the while, sitting quietly behind the scenes at his desk in a small Victorian end-of-terrace house in Wandsworth, South West London, was the softly spoken sixty-something mastermind behind the whole operation.

Martin Mills owns a company called Beggars Group, named after the Rolling Stones 1968 album, Beggars Banquet. It started out as a mobile disco in the early 70s after the Oxford-educated Mills failed to land a job in the music business. A short while later he and his then business partner Nick Austin decided to use their library of disco music as opening stock for a record shop in Earls Court, West London. One day a young man called Gary Numan walked in. It was 1977 and punk had done for funk. The Beggars boys had already dabbled in the genre by recording and distributing a 7" single by The Lurkers, but Numan's electro-punk sound was of another order altogether. They signed him up and an indie label was born.

Label boss Martin Mills (seen here receiving the MBE in 2008) has been a key member of Adele's team

Mills and Austin fell out. It got testy. Mills won and spent the following decades building one of the most formidable indie record labels in the world. HQ is that small house in Wandsworth, which, as the business grew, was knocked through into the house next door, and then the one next door to that, and the one next door to that. It is a suburban empire of alternative-indie music labels consisting of 4AD, which Mills owns outright, and three others in which he has a 50% stake - Matador, Rough Trade, and Richard Russell's XL.

Mills gives the labels free rein - sort of. He is there to support and encourage - and control. He signs every cheque and concludes every deal. His is not designed to be a big business. It is designed to be a cottage industry. The evidence for that can be found in the first Wandsworth house. Before Beggars moved in it served as a Chinese laundry. There was a narrow conveyor belt in the basement used to transport sheets and towels to the ground floor for dispatch. It is still there. And in use. Except nowadays it takes small batches of CDs from the storeroom to reception. It is quaint and cool and knowingly Heath Robinson - ideal for an indie record label. But maybe not the contraption you'd install for shifting millions of units of a mass-market product the world is desperate to get its hands on. It's fair to say Beggars Group was surprised by the Adele phenomenon.

The unassuming suburban face of Beggars HQ - Adele's record label

As was she. It was destabilising. Drugs were never an issue, it is said, but she hit the bottle after 19's success. And then she cancelled a tour to be with a boyfriend, and treated her precious vocal instrument very badly, battering it with booze and scolding it with fags. And then there was the big-sister figure of Amy Winehouse, who had blazed a trail for Brit Schoolers. Her album Frank was a major inspiration to Adele, it made her pick up a guitar.

You can hear Amy Winehouse's musical influence on Adele throughout 19, but most obviously on Right as Rain, which was co-written by Nick Movshon (and others), a close and established collaborator of Amy's. The two singers didn't know each other well, but the whole world knew Amy was up to all sorts and getting away with it…

Amy Winehouse paved the way for Adele, but was a dangerous role model to follow

But Adele is not Amy. She is more grounded, more sorted - a less vivid artistic spirit, maybe. She is not one to take much nonsense from herself or anybody else - Chasing Pavements is about her walking along the street having gone into a pub and lamped her boyfriend for cheating on her. She got back on track. And then, to an extent, repeated the whole cycle of 19 with 21.

Second albums are supposed to be difficult. And it was. But not in the way they usually are. 21 was a juggernaut. And yet Adele still saw herself as a regular working-class girl from London. She played-up the "cor blimey" act to reinforce the impression that she was still plain old Adele Adkins from Tottenham.

Beggars Group was having a similar identity crisis. Martin Mills had dark visions of "more BMWs in the car park". Adele's success was threatening to tilt the company off its axis - sucking up resources, and risking its all-important hipster brand credentials. Indie music is about giving it to The Man, not sending him off to sleep with a cosy lullaby. Adele is many things, but - increasingly - she is not indie cool.

The heat was taken off all parties by an unexpected event. Adele was live on a radio station in Paris when she felt a pop in her throat, "as if a switch had been flicked". Her voice was immediately deeper and she knew something was wrong. She went to get it checked out. The news was not good for someone who makes her living from singing. Or for anybody who appreciates listening to her Jenson Interceptor of a voice. She was in trouble. A polyp in and around her vocal chords had haemorrhaged. There was little alternative but to undergo laser surgery and then rest. Adele was out of the game.

Meanwhile the talk in the music industry was that a big offer - said by some to be north of £80m - was on the table from a major label should she want to quit Beggars. It was considered by many to be a done deal, but nothing happened. 25 duly came out on XL. But the chatter won't go away. There's talk of a strained relationship between Adele and Richard Russell, of "creative differences". The counterintuitive partnership at Beggars that has worked so well for both parties might have run its course. Sony - who have managed her career to such great effect in America - are said to be in the box seat should she wish to move on.

Adele in 2015: "a bona fide A-list international star"

What can it offer her that Beggars cannot? Unprecedented scale - billboards the size of mansions on every street corner in the world, an open chequebook, the chance to direct a movie, the space to write a Broadway musical. A seat at the top table. None of that might appeal. But after years of denial, Adele now realises she is a bona-fide A-list international star on a par with - or even a notch or two above - fellow mononymous singers like Madonna, Prince, Bono and Beyonce.

She is also the power behind Adele Inc - the hands-on chief executive of her own multi-million pound international brand. She openly talks about being a control freak and the boss, which might or might not be connected to an apparent absence of joie de vivre among the musical rank-and-file in videos. She takes the business side seriously.

She was on the Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon last November. He enthusiastically pulled out a vinyl copy of 25 and said "it's a record…" at which point she jumped in quick as a flash, adding "…and CDs" followed by a turn to camera with a big QVC smile.

Flogging the album in both its physical forms was clearly front of mind. She did not want viewers thinking there was some kind of vinyl special limited edition for the die-hards and an internet stream for the rest. That was not an option. She had done a Taylor Swift and withheld 25 from the likes of Spotify, Apple Music and Google Play. Streaming - as she has said and the stats suggest- might be the future, but it is not her present.

The music industry is supportive. She gives it hope. In a global business that has roughly halved in value - from being worth around $30bn a decade or so ago to just under $15bn today - Adele provides living proof that there is still money to be made in recorded music. If you get it right. And she and her team have been impressively consistent performers in most regards, particularly in the marketing department.

Streaming Adele, by Robert Plummer - BBC News business unit

Buying music in a physical format may now account for less than a quarter of the US market, but it hasn't hurt Adele - the massive number of people who buy only one CD a year seem to include a lot of her fans. But what about streaming services? Does it matter that her album is absent from them? After all, casual music listeners, those who don't care about owning a piece of their favourite artists, have embraced Spotify with a vengeance. (The figures here don't include people who download music illegally - 25 is on the Pirate Bay, but its chart is about the only one she hasn't managed to dominate). Maybe if too many big names were to follow Adele's example, streaming services would lose their allure. Adele has said that streaming is "a bit disposable", yet she also sees it as "the future". David Bowie, whose death has been the biggest event to shake the music business so far this year, predicted back in 2002 that music was "going to become like running water or electricity". With even the Beatles now on board, that's a historical trend that Adele stands little chance of slowing, let alone reversing.

From the highly selective choice of TV shows on which to appear, to the hand-picked magazine interviews, the plan is precision-made and ruthlessly executed. And when interest starts to flag another Adele moment will drop - SNL, Graham Norton, James Corden's Carpool, a Brits performance and so on. The choice of Hello as the album-launching single was no accident. Not only did it set the tone and contain all the major themes of 25, it also played to her two most important markets, America and the UK: "Hello from the other side… I'm in California dreaming about how we used to be."

The album's launch was straight out of Steve Jobs's handbook. Control everything, withhold information, build up anticipation, never break cover, keep the message simple, and treat your product's arrival as if it is a major event. Don't worry about feeding the wider media machine. It will gorge itself quite happily on scraps. Adele is up there with Star Wars, Grand Theft Auto, and Apple Corp, as a masterful promoter of her brand.

A billboard in New York advertises Adele's latest LP

Which works as long as the product is good and the reputation unsullied. But it becomes increasingly difficult to square the little-old-me image with a massive international business. It stops ringing true. Regular folk don't have a security team tailing them in a Range Rover, or million-pound tax bills to moan about ("I'm mortified to have to pay 50%"), or Anna Wintour advising them on matters sartorial.

She is smart enough to know this. Her tone of voice in public is changing. It's morphing into a more sophisticated diva-camp. 19 was subdued and spare, 21 was angry and soulful, 25 is ultra pro-pop. But it also belies her narrow frame of reference beyond the world of singers, about whom she is a connoisseur. Where does it go from here? Will there be a backlash? Will she stay at XL? Will her next album, whenever it arrives, be more of the same?

When Adele wasn't Adele

It depends. Has she got a Costello-type Shipbuilding track in her writing locker, or even a Cohen-esque Famous Blue Raincoat? A song, in other words, that shares the same sentimental ingredients of her previous work, but is less introspective and more observed.

I hope so. Her voice is such a fine instrument it deserves top quality material. It marks her out. Madonna, Michael Jackson, Miley - in fact the majority of major pop stars - have relied on videos and spectacle to build their audience. Adele has not. She has relied on her singing and her songwriting, and so far, they haven't let her down.

Adele performs at the 2013 Oscars

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

All images subject to copyright