Cologne attacks: Germans left feeling vulnerable

- Published

The New Year's Eve attacks on women in Cologne are still reverberating in Germany, with the resignation of the city's police chief on Friday, and news that migrants were among the suspected attackers. The BBC's Jenny Hill looks back on a week that has left both women and asylum-seekers feeling vulnerable.

Cologne's cathedral is a gothic colossus of a building. On a drab winter's day its dark-stoned grandeur is especially imposing, rising above the bright lights, glass and concrete of the adjacent railway station. The soot-blackened faces of its carved angels are melancholy. I stood here a few days ago, wrapped up against a bitter wind, and watched the huddled commuters rushing past on the pavement below.

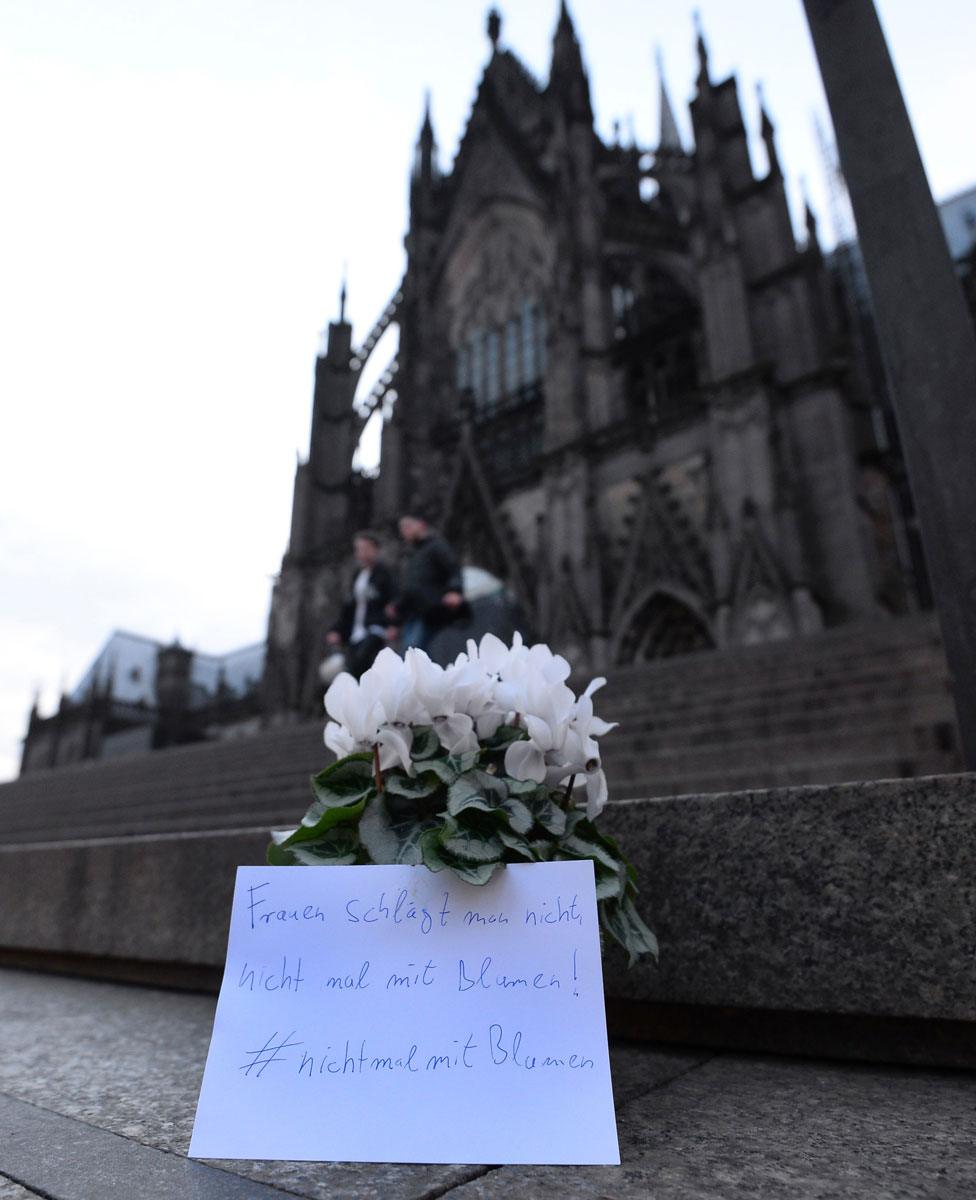

And then I spotted the flowerpots, three tiny plants left on the steps of the cathedral. Small white flowers shivering in the wind, ignored by the people walking by. There was a note stuck to one of the pots. "One doesn't attack women," it read. "Not even with flowers." No signature, no way of telling who left them here.

Because of course this is where - on New Year's Eve - in the chaos of celebration, scores of women were sexually assaulted and robbed.

Even now, no-one - and that includes the police - really knows what happened. Victims describe how suddenly gangs of drunken men suddenly surrounded them. They threw fireworks; there was screaming and noise. The young women say there were hundreds of attackers. And few police. No protection. All this took place in the heart of one of Germany's biggest cities.

Cologne station on New Years's Eve

A lone woman outside the station on Thursday

The attacks have outraged this country, igniting what was already a febrile national debate. Germany is struggling with record levels of immigration. Last year, well over a million people arrived here seeking asylum.

There were significant numbers of Syrian, Afghan and Iraqi men, carrying official asylum papers, in the crowd that night. Critics have seized on all this as evidence that Angela Merkel's open-door refugee policy has put German citizens at risk.

There's also anger at the police, who initially said that New Year's Eve in Cologne had passed peacefully. And there's suspicion of the media who didn't report the attacks until a number of days later. One broadcaster has publicly apologised for the delay. There's now a fear that the warm welcome Germans offered to migrants last year may have backfired.

One of the young women who was in the square on New Year's Eve invited me to the home she shares with her parents on the outskirts of Cologne.

A small - and very enthusiastic - Jack Russell greeted me at the door. That's Sparky, Michelle told me, smiling as her father gathered the dog up and took him away. I could hear Sparky's yaps of protest from the next room.

Michelle is 18. As she told me about herself - she's an economics student - I glanced around; pictures of the family smiled down from the wall behind her.

She described the moment she and her friends were surrounded, then assaulted by a group of 20 to 30 men. She didn't understand the language they were speaking. "They grabbed our arms, pushed our clothes away tried to get between our legs," she said.

In the corner of the room, Michelle's mum folds her arms.

"The police should think now about what they do to help us," Michelle continued. "This is not a situation that's normal in Germany or the Western world."

More German women have been signing up for self-defence courses since the attacks

But she worries. "It would be wrong to blame refugees," she tells me. "They need our help."

Many here fear a violent backlash against the 4,000 asylum-seekers living in Cologne.

I met a young Iraqi man with striking green eyes outside one of the city's larger refugee homes. It's a depressing place, a red-brick building with dirty windows overlooking a busy dual carriageway.

Even so, Hassan grinned as he described his plans to stay in Germany and work as a mechanic. "I want to thank Angela Merkel," he enthused in his newly acquired German. "I love this country!"

I asked him if he'd heard abut the attacks and for a moment he looked sad. "Yes," he replied. "I'm so sorry this has happened. But Iraqi and Syrian men are good people."

Hassan hopes his mother and brother will join him here in Germany. As he walked away through the barred gate of the compound, I couldn't help but wonder whether that will happen now.

It feels like a long time since Angela Merkel told Germany it could cope with the vast number of migrants arriving. Back then, so many were impressed by her moral direction. Germany was, she argued, a rich stable country with much to offer.

But I think of those fragile flowers left at the cathedral - delicate petals in a harsh winter wind.

"Twenty or 30 men surrounded us and we couldn't even move anymore"

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.