Was there a communist witch-hunt at the BBC?

- Published

Newly released files from the 1950s show the extent to which the government was monitoring the BBC for communist and Soviet sympathisers. Despite pressure from one driven MP, the authorities resisted the urge to conduct a purge.

In June 1952, a Conservative MP urged the Prime Minister Winston Churchill to investigate Communist activities in Britain. "We have traitors in our midst," wrote Sir Waldron Smithers, "and although I should deplore suppression of free speech they should be treated as traitors."

The letter was contained in one of Churchill's files that has only now been released to the National Archives, more than 60 years later. It was to be closed "indefinitely" according to a note on the front of the brown card cover.

Historians believe that's because it concerns MI5 - and it's only in the past few years that their Cold War files have been released to the public.

In 1952 Smithers urged the prime minister to set up a "committee presided over by an English judge or QC… who could make an extensive enquiry into communist activities and report to you".

This was the era when Senator Joseph McCarthy was the driving force behind high profile and controversial hearings into alleged Communist infiltration in the United States, especially in public service.

In 1947, Smithers had asked in parliament if the prime minister [then Labour's Clement Attlee] would "set up a committee of this House on Un-British Activities, on the lines of the Committee on Un-American activities". The government refused point blank. Smithers asked if communists would be outlawed and their funds seized. He was again refused.

The Conservative MP Sir Waldron Smithers

Five years later, Smithers was particularly worried about communist sympathisers in the BBC: "In the event of war or a major crisis… these fellow travellers, with their intimate knowledge of the mechanisms of broadcasting, could in half an hour cut wires and damage equipment seriously to hamper broadcasting."

He included a list of BBC employees who he understood were communists, or sympathisers, mostly in the new Russian service. Among them was a "Mr Goldberg", who he described as a "Jew… who controls the selection of programmes and is a communist". Anatol Goldberg was in fact head of the BBC Russian service - an important and influential figure.

Churchill asked MI5 to investigate communist sympathisers at the BBC

Churchill was concerned enough to send the letter - and names - to MI5, via the Home Office, for further investigation. They wrote back saying the prime minister should not be worried. "In the considered view of the Security Service, communist influence in the BBC is very slight and does not constitute a serious security danger."

For many years, MI5 had been vetting BBC staff. They believed there were only 147 communists, suspected communists, or communist sympathisers, out of a staff of 12,200. The home secretary believed a major inquiry - like that suggested by Smithers - "might cause much embarrassment without serving any useful purpose".

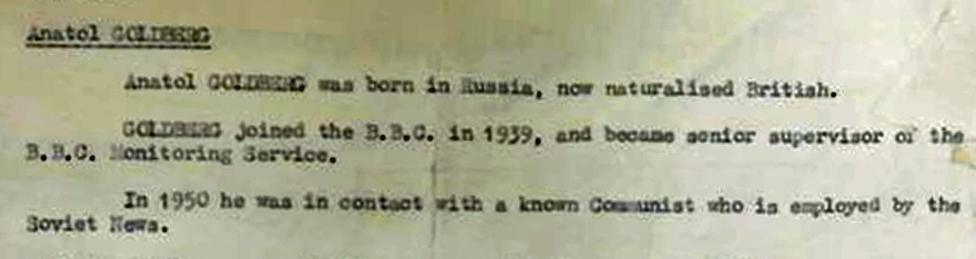

Separately, MI5 forwarded their views on Smithers's blacklist. There was no evidence that any of them had been Communist Party members. Anatol Goldberg, they said, had been in contact in 1950 with a known communist, who was employed by Soviet News - but nothing more.

MI5's briefing notes on Anatol Goldberg - "he was in contact with a known Communist"

Peter Fraenkel, former head of the BBC Russian Service, knew Anatol Goldberg well. "He was a wonderful raconteur," he says. "One of the best I've ever known". He isn't surprised that Goldberg had been in contact with Russian journalists in London - it was part of the job. He wasn't a communist himself.

Fraenkel says Goldberg never spoke about his problems with MI5, but he knew some people felt his tone was too gentle: "He didn't sock it to them enough." Fraenkel says Goldberg's approach was more subtle - to listen to people, and then ask them questions like: "The revolution was supposed to deliver this and this this… has it done so?"

Goldberg's approach was successful. The BBC Russian service was believed to be more popular and more trusted than its US-sponsored rivals - though of course there were no reliable ratings. MI5 and the Foreign Office did succeed in part - in 1957 Anatol Goldberg was shunted out of his post. He remained a commentator.

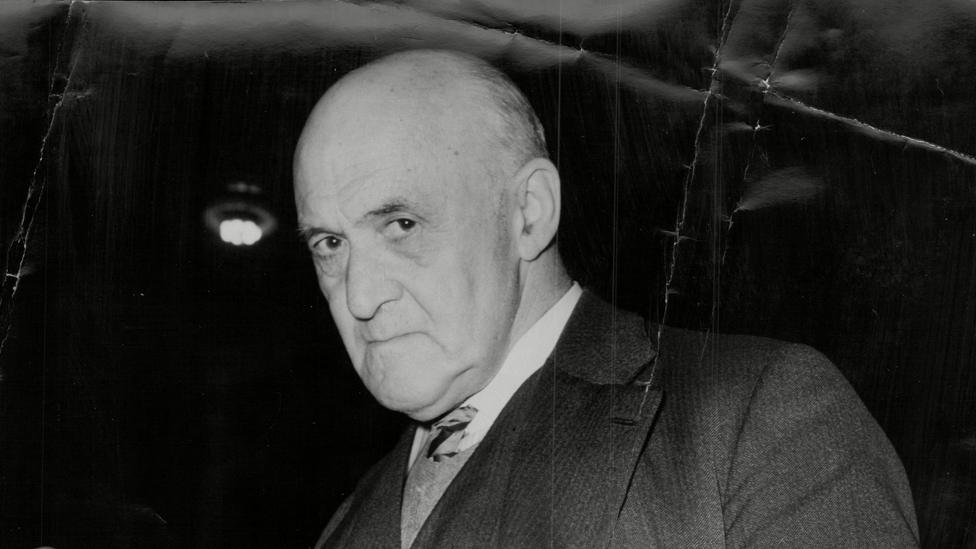

Anatol Goldberg fell under suspicion while head of the BBC Russian Service

Fraenkel says his predecessor at the Russian section, the former MI6 officer Alexander Lieven, had a poor view of his erstwhile colleagues at MI5. He advised Fraenkel not to trust their vetting - but to rely on his own Russian staff, who would quickly "sniff out" an infiltrator.

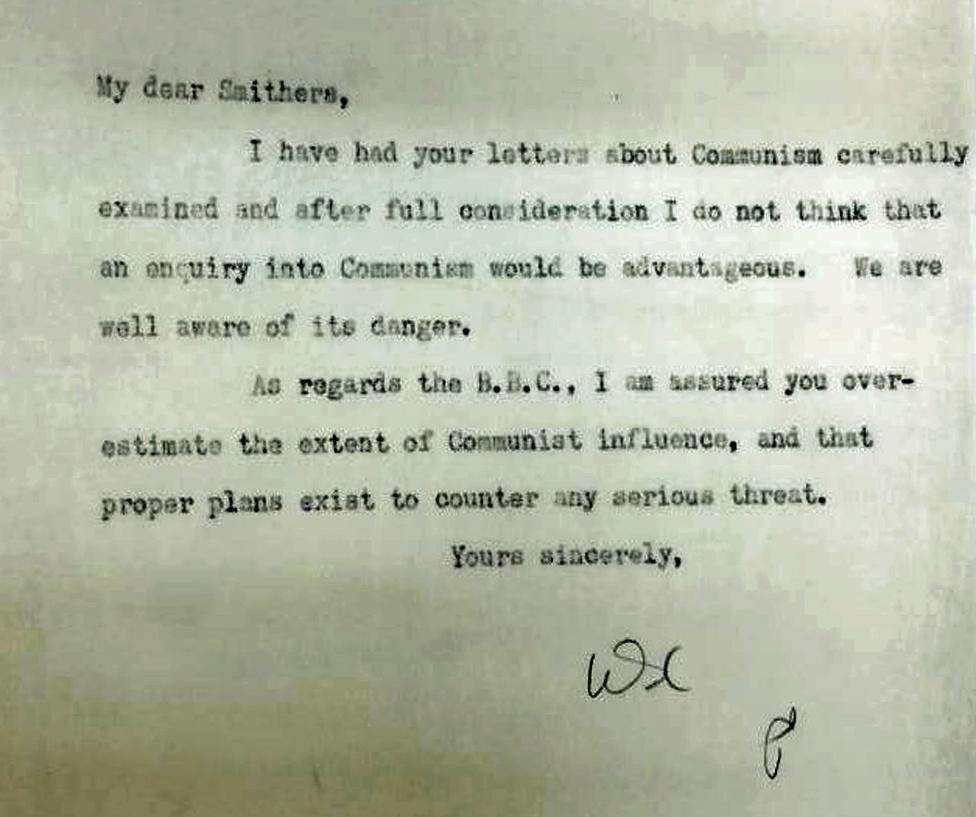

Churchill wasn't fully convinced by Smithers's concerns. "I am assured you overestimate the extent of Communist influence and that proper plans exist to counter any serious threat."

Winston Churchll's reply to Waldron Smithers

However, the prime minister retained a private interest. A year later he asked the Cabinet Secretary, Norman Brook, to check how many communists or communist sympathisers remained on the BBC staff. There were 100 - 60 in relatively junior positions. Of the 40 in more senior roles, 31 were in the overseas services. Brook said that the Director General Sir Ian Jacob was aware of the "risks" - that they'd try to influence the content of broadcasts, but that "he is certainly on the watch for any signs of this - he is of course helped by knowing precisely who the suspects are and what positions they hold".

The director general and the home secretary were opposed to a policy of "eradication" as they feared sacking people for their political beliefs would cause "such a political storm that it would do more harm than good".

Sir Ian Jacob, BBC director general 1952-59

Jean Seaton, author of Pinkos And Traitors, about politicians and the BBC, believes this was a rather British approach - to monitor rather than blacklist. While the closeness between the BBC, government, and MI5 may look troubling now, she says it was an effect of World War Two. Churchill and Jacob, for instance, had worked closely together:

"These are men who'd worked through a national emergency… they'd shared concerns... they shared a world view. In that sense they don't have the alarm bells round MI5 that someone who'd always worked on Newsnight might."

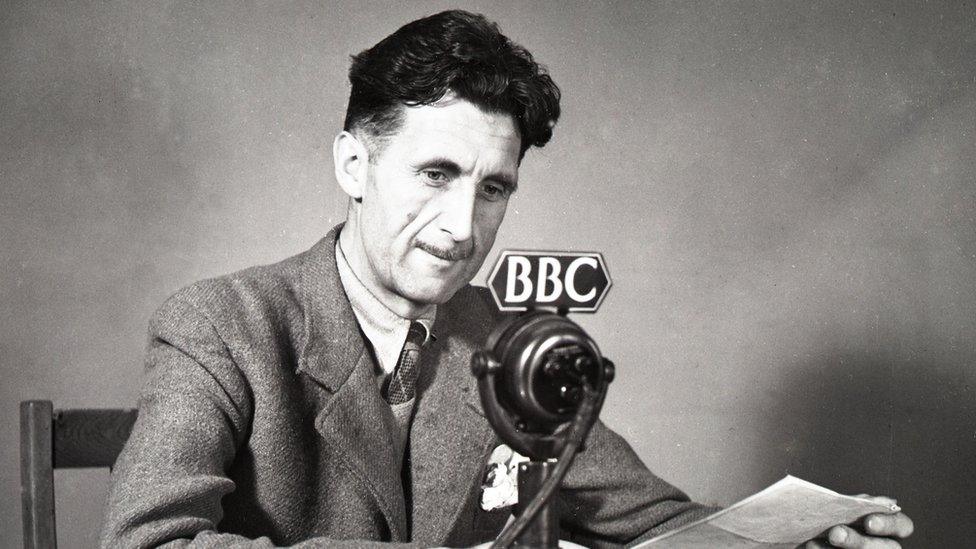

George Orwell's list of communist sympathisers

Shortly before his death in 1950, the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm sent a list of names to the Information Research Department, an anti-communist propaganda unit set up by the post-war Labour government

The list comprised people (mostly writers) Orwell considered too sympathetic to Soviet Russia to be suitable for work at the IRD; names included the film star Charlie Chaplin, the writer JB Priestley and the Labour MP Tom Driberg

List was made officially public in 2003; one commentator called his action "a terrible mistake", but Orwell's biographer Bernard Crick said: "He did it because he thought the Communist Party was a totalitarian menace"

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.