Would it be wrong to eradicate mosquitoes?

- Published

The mosquito is the most dangerous animal in the world, carrying diseases that kill one million people a year. Now the Zika virus, which is carried by mosquitoes, has been linked with thousands of babies born with brain defects in South America. Should the insects be wiped out?

There are 3,500 known species of mosquito but most of those don't bother humans at all, living off plant and fruit nectar.

It's only the females from just 6% of species that draw blood from humans - to help them develop their eggs. Of these just half carry parasites that cause human diseases. But the impact of these 100 species is devastating.

"Half of the global population is at risk of a mosquito-borne disease," says Frances Hawkes from the Natural Resources Institute at the University of Greenwich. "They have had an untold impact on human misery."

Deadly mosquitoes

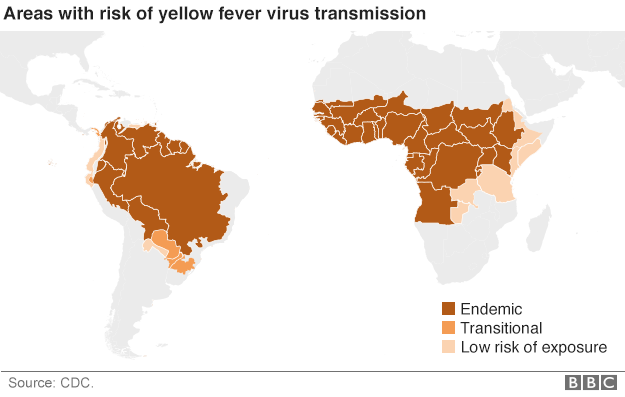

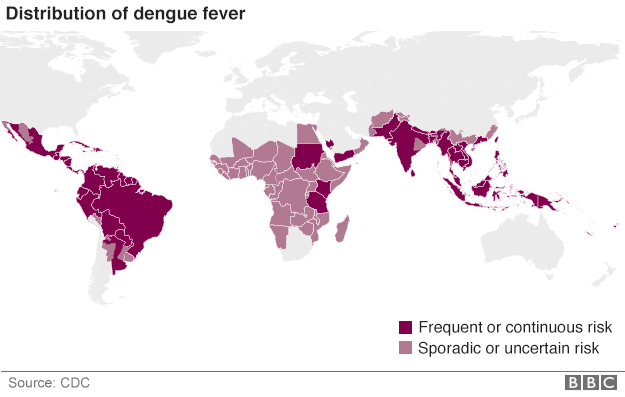

Aedes aegypti - spreads diseases including Zika, yellow fever and dengue fever; originated in Africa but is found in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world

Aedes albopictus - spreads diseases including yellow fever and dengue fever and West Nile virus; originated in Southeast Asia but is now found in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world

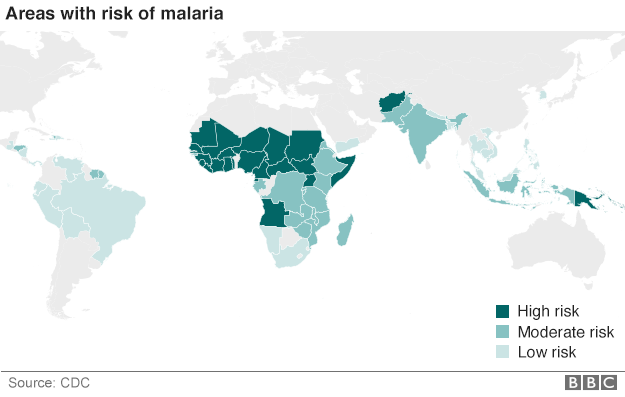

Anopheles gambiae (pictured above) - also known as the African malaria mosquito, the species is one of the most efficient transmitters for the spread of the disease

More than a million people, mostly from poorer nations, die each year from mosquito-borne diseases including malaria, dengue fever and yellow fever.

Some mosquitoes also carry the Zika virus, which was first thought to cause only mild fever and rashes. However, scientists are now worried it can damage babies in the womb. The Zika virus has been linked with a spike in microcephaly - where babies are born with smaller heads - in Brazil.

There's a constant effort to educate people to use treated nets and other tactics to avoid being bitten. But would it just be simpler to make an entire species of disease-carrying mosquito extinct?

Biologist Olivia Judson has supported "specicide" of 30 types of mosquito. She said doing this would save one million lives and only decrease the genetic diversity of the mosquito family by 1%. "We should consider the ultimate swatting," she told the New York Times., external

In Britain, scientists at Oxford University and the biotech firm Oxitec have genetically modified (GM) the males of Aedes aegypti - a mosquito species that carries both the Zika virus and dengue fever. These GM males carry a gene that stops their offspring developing properly. This second generation of mosquitoes then die before they can reproduce and become carriers of disease themselves.

About three million of these modified mosquitoes were released on to a site on the Cayman Islands between 2009 and 2010. Oxitec reported a 96% reduction in mosquitoes, external compared with nearby areas. A trial currently taking place on a site in Brazil has reduced the numbers by 92%.

So are there any downsides to removing mosquitoes? According to Phil Lounibos, an entomologist at Florida University, mosquito eradication "is fraught with undesirable side effects".

He says mosquitoes, which mostly feed on plant nectar, are important pollinators. They are also a food source for birds and bats while their young - as larvae - are consumed by fish and frogs. This could have an effect further up and down the food chain.

However, some say that the role of mosquito species as food and pollinators would quickly be filled by other insects. "We're not left with a wasteland every time a species vanishes," Judson said.

But for Lounibos, the fact this niche would be filled by another insect is part of the problem. He warns that mosquitoes could be replaced by an insect "equally, or more, undesirable from a public health viewpoint". Its replacement could even conceivably spread diseases further and faster than mosquitoes today.

Science writer David Quammen has argued, external that mosquitoes have limited the destructive impact of humanity on nature. "Mosquitoes make tropical rainforests, for humans, virtually uninhabitable," he said.

Rainforests, home to a large share of our total plant and animal species, are under serious threat from man-made destruction. "Nothing has done more to delay this catastrophe over the past 10,000 years, than the mosquito," Quammen said.

But destroying a species isn't just a scientific issue, it's also a philosophical one. There would be some who would say it is utterly unacceptable to deliberately wipe out a species that is a danger to humans when it is humans that are a danger to so many species.

"One argument against is that it would be morally wrong to remove an entire species," says Jonathan Pugh, from Oxford University's Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics.

And yet that's not an argument we apply to all species, says Pugh. "When we eradicated the Variola virus, which caused smallpox, we rightly celebrated.

"We need to ask ourselves, does it have any valuable capacities? For instance, is it sentient and therefore has the capacity to suffer pain? Scientists say mosquitoes don't have an emotional response to pain like we do.

"Also do we have a good reason for getting rid of them? With mosquitoes, they are the main carriers for many diseases."

The question is likely to remain hypothetical, whatever the level of concern over Zika, malaria and dengue. Despite the success of reducing mosquito numbers in smaller areas, many scientists say knocking out an entire species would be impossible.

"There's no silver bullet," says Hawkes. "Field trials using GM mosquitoes have been a moderate success but involved releasing millions of modified insects to cover just a small area.

"Getting every female mosquito to breed with sterile males in a large area would be very difficult. Instead we should be looking to combine this with other techniques."

Innovative ways of tackling mosquitoes are being developed across the world. Scientists at Kew Gardens in London are developing a sensor, external that can detect each different species of mosquito from its distinctive wing beat. They plan to equip villagers in rural Indonesia with wearable acoustic detectors to track disease-bearing mosquitoes. This would help them manage future outbreaks.

Meanwhile, scientists at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine have worked out how female mosquitoes are attracted to certain body odours, raising hope for more effective repellents, external.

Another promising avenue is to make mosquitoes resistant to the parasites that cause the diseases. In Australia, the Eliminate Dengue programme, external is using naturally occurring bacteria to reduce the ability of mosquitoes to pass dengue between people.

"This is a more realistic approach for mitigating mosquito-borne disease," says Lounibos.

Meanwhile, scientists in the US have bred a GM mosquito with a new gene in the laboratory that makes it resistant to the malaria parasite.

"We are playing an evolutionary game with mosquitoes," says Hawkes. "Hopefully it's one we can get on top of over the next 10 to 15 years."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.