Did China invent football?

- Published

When England hosted the European Championship 20 years ago, the anthem of the home team - also a number one single - had the catchy chorus "It's coming home… football's coming home." But China can also claim to be the home of football, explains Michael Wood.

Chinese President Xi Jinping is famously a football fan - Manchester United, as it happens - and on his visit in October to Manchester City's Etihad Stadium, one subject that cropped up was the Chinese invention of football.

This might have been a surprise to Gary Neville, Mike Summerbee, and the other one-time stars of the game who met Xi, but it was acknowledged by Kevin Moore, director of the National Football Museum.

"While England is the birthplace of the modern game as we know it, we have always acknowledged that the origins of the game lie in China," said Moore, as he showed Xi and Prime Minister David Cameron round the museum.

But how much of the game did China invent?

A player in traditional cuju clothes at Linzi Football Museum in Shandong, China

England has had few football highlights since Wembley 1966, but we have always comforted ourselves that we invented the game that is now played all over the world.

Sheffield FC, the world's oldest club still playing, was the first to lay down rules in 1858 - you could still use your hands then, and that became Australian Rules football when exported down under. Then through the 1860s the game swiftly evolved to the one we have today: no catching, 11 a side, corners and penalties, then the 90 minutes. The rest is history. But what about football much further back in China?

All human societies play games. Kicking a ball is probably ubiquitous whether just a ball of cloth, or a skin stuffed with feathers or filled with air.

But complex games and team sports have tended to arise in big civilisations - the higher the cultural level of a society, the greater the complexity of interaction, and hence perhaps the more complex the forms of sport.

This is not always the case. The ancient Greeks for example preferred individual not team sports. One of my Greek friends was only half joking when he expressed amazement when they won the 2004 Euros: "I never knew you could get 11 Greeks to actually play together like that!"

The Story of China

Michael Wood explores the stories, people and landscapes that have helped create China's distinctive character over 4,000 years.

Watch episode two, Silk Roads and China Ships, on Thursday 28 January at 21:00 on BBC2

Viewers in the UK can watch the first episode, Ancestors, on the BBC iPlayer

But in China for well over 2,000 years, they have played the game of "kickball" - cuju, pronounced tsoo-joo. Today spelled zuqiu, it's still the word used for football.

The heyday of Chinese football was in the Song Dynasty, from 960 to 1279AD. Kickball then was part of the wider urban culture of entertainment, sports, leisure and pleasure and there were different forms. In one version the idea was to keep the ball in the air as long as possible, but there were also competitive team games in which the idea was to get a ball into a goal.

Such a game, played by professionals, is described in a famous book, The Splendours of the Eastern Capital, about life in the capital, Kaifeng, in about 1120.

Kickball clubs had managers, trainers, and captains, and in recent fascinating research, German scholar Hans Ulrich Vogel has turned up club handbooks that show what kickballing life was like then.

The members were often young men from wealthy families, though there were also itinerant professional kickballers, whom you could stick in your team as sleepers.

The Song Emperor Taizu played kickball

Cuju was played as entertainment at court banquets or the reception of foreign envoys. Even emperors played kickball. There's a Song Dynasty painting of the Emperor Taizu himself apparently playing keepy-uppy, surrounded by beefy courtiers. Or are they kickball stars, like David Beckham on a photo op with Prince Charles today?

So what about the rules? In the Song Dynasty they had printed books like The Illustrated Rules of Kickball by Wang Yuncheng. This talks about two main forms of the game, one with and one without a goal.

The goal was about 10m high, with a net of coloured rope, and in the middle a hole one foot in diameter.

The two teams wore different strips, for example all red v all green. Captains wore hats decorated with little stiffened wings - the equivalent of the captain's armband today. Other players wore hats with curling wings.

One team began by passing the ball around until the "assistant ball leader" finally passed it to the "ball leader" or "goal shooter" who shot at the hole in the goal's netting. The other team then took up the ball and started its own round in the same way. There were no goalkeepers.

The team that got the most goals won. Successful kicks were rewarded with drum rolls, pennants and wine - maybe something the Premier League should consider?

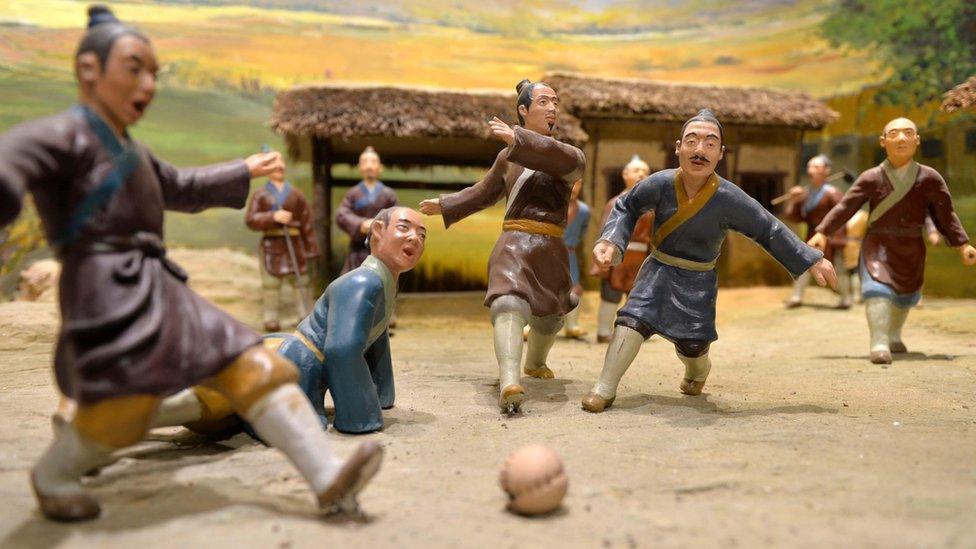

Model of traditional cuju at the Linzi Football Museum in China

It all sounds a bit static compared with watching Neymar and Messi, and as you'd expect in a Confucian society, kickball clubs were keen on the key virtues of benevolence and courtesy. A great player was one who embodied "the spirit of the game".

The "Ten Essentials of Kickball" included respect for other players, courtesy and team spirit. There was to be no un-gentlemanly behaviour, no dangerous play, and no hogging the ball. In other words, as we used to say, "Play up and play the game."

What a contrast with the ancient Greek athletes where only victory counted and if that needed gamesmanship, or brutal professional fouls, then so be it.

Some top players became rich and famous, and great kickball players and their teams were invited to take part in imperial celebrations. We even know the names of the star players.

How football has evolved since the Song Dynasty

But it wasn't chiefly about fame or money. Handbooks praise the positive effects of the game. Kickball "promotes happiness" and is "an example to rowdy youths".

"It strengthens the body, supports the digestion and helps combat obesity." It also "releases tension, raises the spirits, and helps you forget the daily grind" - a feeling anyone will know who has played football at whatever level, even in the park or on the school field.

Women were also enthusiastic fans. A 9th Century poem describes the kickball performance of Li Guangyan, a chancellor and general in his day job.

"Quick as a monkey on the ballfield, with a falcon's grace / Three thousand ladies tilted their heads to watch him / Trampling shiny earrings as they crowded for a view / Standards bobbed and waved, banners flashed and shone."

It could be George Best in his prime!

But as Vogel shows, women played too. An illustration shows a couple playing kickball in a garden, the lady with her hair pinned up out of the way, garments flying.

One gossip writer of the Tang dynasty (618-907AD) tells the story of three teenage girls in shabby clothes and wooden slippers standing under a tree while some soldiers were playing kickball nearby. The ball rolled towards one of the girls who "calmly extended her leg, controlled the ball on her toe, and then powerfully kicked it back in a high arc". A full-on game then ensued, to the delight of onlookers. Bend it like Guangyan!

So can we say football originated in China?

Well it's true that the Chinese had clubs, rules, and fans more than 1,000 years ago. But the various versions of kickball were a long way from modern football as defined in Sheffield in the 1860s. It was the British codifying of the rules that made association football the world's game, the sport of the people, not just of the toffs. So maybe we should stick to calling the Chinese version "kickball"?

Xi Jinping has said his big ambition is for China to get a team to the World Cup, then to host it, and then eventually to win it. Certainly they have a far better claim than some recent hosts (let alone Qatar). And of course with their fantastic infrastructure, and their huge fan base, I have no doubt China could put on a great World Cup.

As for winning it, well that will take longer. The standard of Chinese football in my experience is not yet high enough. But given the Chinese ability to learn, their willingness to invest in grassroots sport, and their sheer drive - don't bet against it!

And if they do, maybe we could pardon them for reversioning England's Euro 96 anthem. Zuqiu hui jia le! - Football's Coming Home.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.