Syrian refugees settle into new lives in Canada

- Published

Sawsan and Abdel Malek al-Jasem and their family

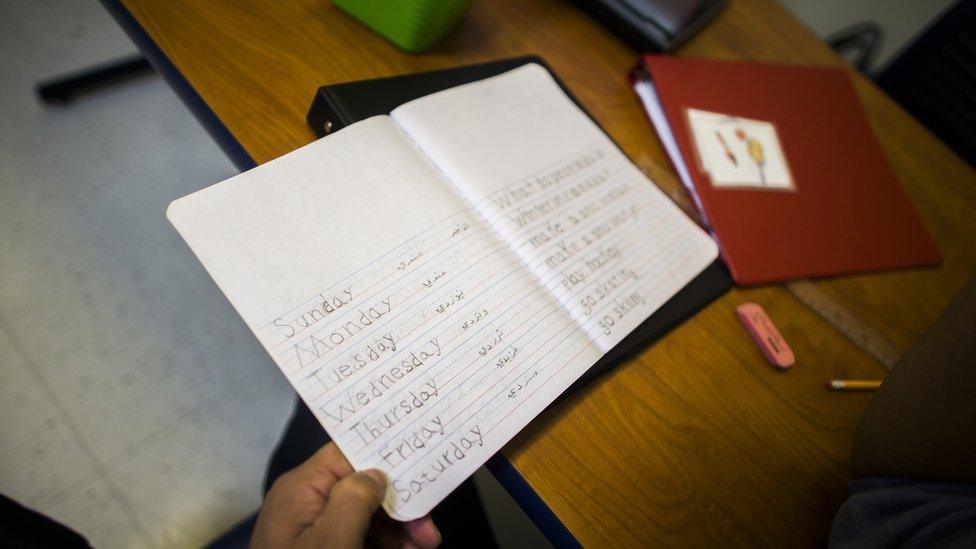

In a small, crowded classroom in tiny Belleville, Ontario, Syria native Abdel Malek al-Jasem is learning some very important terms in English.

Coat, gloves, toque, scarf and boots. He scribbles them in a notebook next to their Arabic translations.

He will need all of that gear as he adjusts to life in Canada.

Jasem arrived in October of last year after four years in Lebanon, where he and his family sought refuge after bombing in their village outside of Hama, Syria, pushed them out.

He and his wife have eleven children, including two sets of twins, ranging in age from a toddler to a college-aged boy.

Abdel Malek al-Jasem laughs with his ESL instructor Anu Greenwood during an English lesson

They were anxious and scared to arrive in their new country. The transatlantic journey was also the family's first time on a plane.

They touched down in Canada safely. Now, the journey for the Jasem family is learning English, going to school and finding work.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is making resettling Syrian refugees one of the priorities for his new Liberal majority government.

The government set a goal of resettling 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of February. About 26,000 arrived in Canada by the end of February, 8,567 of them privately sponsored.

They had aimed to reach that goal by the end of 2015, but ended up pushing it to February.

By the end of 2016, the government aims to have at least 25,000 government-assisted refugees in Canada.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau met refugees at the airport in December 2015

"This is something that we are able to do in this country because we define a Canadian not by a skin colour or a language or a religion or a background," Trudeau said at Toronto-Pearson International Airport last December, during a well-publicised event that led to images of Mr Trudeau giving coats to refugees after they emerged from a plane.

"But by a shared set of values, aspirations, hopes and dreams that not just Canadians but people around the world share."

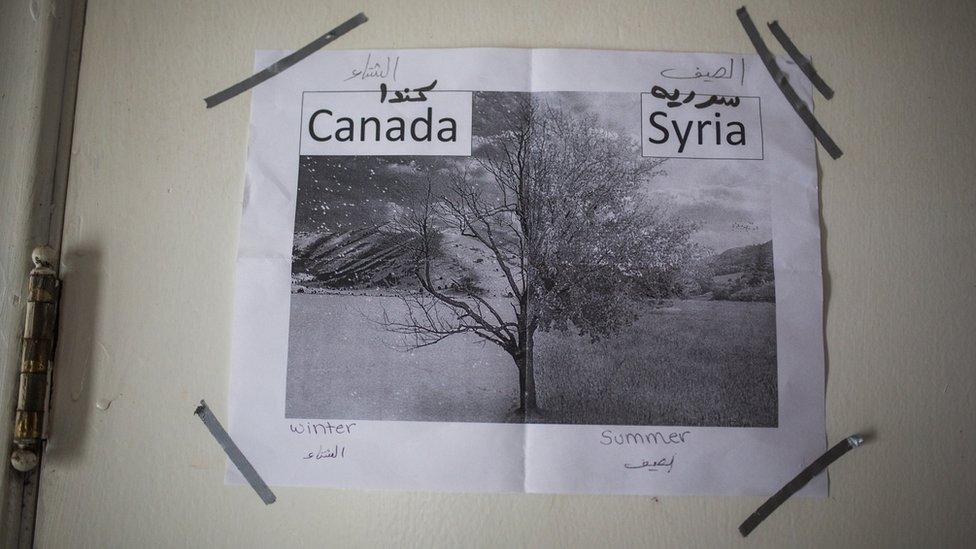

Jasem and his children are learning how to live in their new country. They learned to ice skate in January. They don't like the cold and snow in Canada, they said, but like all things, it will just "take time" to get used to.

"Everything back home is gone. Everything is demolished… there's nothing left to go back to," said Jamal Bsat, who was working as a translator in the classroom with Jasem.

Jasem said he prefers his old wardrobe, though. In Canada, he said you have to wear "too many clothes on top of each other".

How does it work in Canada?

The Jasem family's first temporary home in Picton, Ontario, was paid for by a group of sponsors organised by Toronto's Ryerson University's Lifeline Syria Challenge.

Fadl Ahmad, and Ramaz eat lunch inside their temporary home in Picton, Ontario

The university founded the programme, later joined by OCAD University, University of Toronto and York University. It's setting a precedent of sorts for successful private sponsorship of Syrian refugees in the country.

The Canadian government has not yet set a cap on how many privately sponsored refugees they will accept.

Connected by Ryerson's programme, groups of about 10 people per family arrange housing, English classes, doctor's appointments, shopping trips and anything else needed to navigate life in the refugees' new homes.

At the end of February, the programme had 87 teams of sponsors, and 15 families from Syria - 93 refugees total.

Wendy Cukier, executive director of the programme, said families who receive private sponsorship do better than those who come to Canada as government-sponsored refugees.

Government-sponsored refugees are eligible for a year of financial help. For families with private sponsors, the help can extend beyond one year. They become permanent residents upon arrival, entitled to Canada's social programmes like healthcare. Once they start working, they are subject to the same rules and taxes as any Canadian resident. Within a few years, they can apply for full citizenship.

Running home from school

To get to Canada, refugees usually must be registered as such by the United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees.

For Lifeline Syria, which is categorised as a Sponsorship Agreement Holder programme, this is not required, but recommended.

Some refugees have relatives in Canada, which may speed their applications along.

Refugees can indicate they are interested in going to Canada, but women and complete families have the best chance of getting to the country as government-sponsored refugees. Each refugee, private or government-sponsored, undergoes a security screening that includes biometrics, security and health, and some are interviewed by visa officers.

In the US, the Obama administration has said it wants to resettle about 10,000 Syrian refugees before the end of 2016.

Syrian refugees who end up in the US must also register as refugees with UNHCR, and a small number are recommended to resettle in the US.

Having family in the US helps. After that, the State Department takes over, and the Department of Homeland Security decides whether an individual application is approved.

The process for approval then takes 18-24 months, and then refugees are admitted at a 50% acceptance rate, after undergoing, as one US official put it, "the most rigorous screening of any traveller to the US".

Some politicians have said they want to halt the US programme entirely.

Meanwhile, the challenge for Ryerson's programme, said Cukier, is deciding when to stop.

"Do we keep going or do we say, we've done our bit?" she said in January.

Settling into snowy Canada

Over in rural, snow-covered Picton, houses are kilometres apart, the long roads dotted by farms. The Jasem family is settling in.

Their youngest boy ran around the home rambunctiously on a January afternoon, playing with a toy plane and getting dangerously close to knocking over mugs of hot chocolate.

Getting ready to go outside

Slowly, all the other children arrived home from school on yellow school buses, bright against the white landscape. The teenage boys wrapped their arms around their younger siblings as they bounded into the house.

"Good job, good job, good job," one young girl said, repeating a favourite phrase learned in school.

Another practises, "Hi, how are you? I'm good."

One teenage brother said he was happy to be going to school after working long hours back in Lebanon as a butcher, but he wants to get a job as soon as possible so he can contribute to the family, and as his sponsor said, get out of the house on the weekends.

"My friend in Lebanon told me working at McDonald's is good," he said.

One of the family's sponsors, local art gallery owner Carlyn Moulton, said she would talk to the manager of the McDonald's in town to get him a job, filling his eyes with excitement.

Government data shows that immigrants to Canada in the past five years have had an easier time gaining employment in Western Canada, and that many immigrants are employed in the service sector.

Most refugees are eager to start working, not wanting to be a burden on their sponsors.

The Al Hasan family (left to right), Rania, Fusie, Nasimi, Batal, and Ali

"You are going to do more than work at McDonald's," she said. "Maybe you could manage a McDonald's."

Another son spoke to the model United Nations conference in his school recently. The topic was refugees and displaced persons.

"This was the first time they'd met a person as a refugee, to practically hear someone say our house was bombed," said Moulton. "It profoundly moved the other kids."

'Everyone has the same value'

Some families have been able to get most of their members over to Canada, but had to leave some loved ones behind in the process.

In Mississauga, a community near Toronto with a large Muslim population, the Al Hasan family arrived in January.

Syrian refugee sponsor Valerie Pringle helps refugee Nasimi Al Hasan put on the new shoes

Before, they all lived in one room in Lebanon, where they spent four years before getting to Canada. Now, the family is desperately trying to get two more daughters over to the country, one currently in Iran and one in Turkey.

On a day not even a month after arriving in Canada, they purchased so much while out shopping with their sponsor that they struggled to bring it upstairs. Bags of ground turkey and bread sagged under one child holding a new toaster.

Data, external from the government's Internal Citizenship and Immigration Department released in 2012 suggests privately sponsored refugees who arrived in Canada between 1993 and 2007 do better than government-sponsored ones. They are less likely to be on social assistance two years after resettling in Canada and more likely to have a higher salary.

Before arriving in Canada, the Al Hasan family's daily grievances and worries were quite different than how to get bags of groceries into the lift.

"We just pray and hope that not another person will die in this situation, whether it's in hands of the crazed [so-called Islamic State] - in the name of Islam, it's so ridiculous to us - it's all people just dying," said Batal al-Hasan, the patriarch of the family, speaking through a translator.

"We're hoping it will stop like right now, and not a single more person will suffer and the country will return and rebuild. I hope with God's will it will stop and change. If not for our generation, for future generations."

One of his daughters said of Canada, "There's so much freedom, I'm very, very happy."

Nasimi plays in the snow outside of their apartment building in Mississauga, Ontario

"She couldn't go out, she just stayed at home [in Jordan]...you feel like you're choking, no freedom whatsoever," said Mariela Barazi, one of the family's sponsors also serving as a translator.

Public opinion on refugees is mixed, despite the common image of a warm, welcoming Canada.

In January, a man bicycling by the Muslim Association of Canada Centre in Vancouver pepper-sprayed a group of Syrian refugees standing outside. Mr Trudeau condemned the attack.

A poll, external released in late February of 1,507 Canadians by the Angus Reid Institute found that 52% support the government's refugee plan, and 44% oppose it. Forty-two percent say Canada should stop taking in Syrian refugees immediately.

Asked if the family would return to Syria should things resolve, Hasan said their new home is Canada.

"We want to establish ourselves here," he said. "We would love to be able to go visit our Syria and visit Syria in the future, but for the future for our kids, we want to establish somewhere where we can build a life."

Rania Alhasan smiles and holds up her Canadian themed mittens

"Here, everyone has the same value."

Progress, almost two months later

By early March, the Jasem family moved into a new home in Picton. They are renting it from their sponsors, who purchased it.

The home has a backyard and a fireplace, and the children can walk to school.

Eventually, the Jasem family will purchase it from their sponsors.

Ahmed, the son who wanted to work at McDonald's, has been hired at a local restaurant in Picton for the summer and is working part-time, along with some of his brothers, at a local canoe and kayak company.

Abel Malek al-Jasem is starting to look for work. Moulton said he would really love to work on a farm.

Some of their relatives have also arrived in Canada and have moved in across the street.

"Lots of progress has been made," said Moulton. "None of this would have happened if they were government-sponsored."

The younger children are doing very well in school, picking up English quickly, the school principal recently said.

Jasem now has a car and will soon no longer rely on the sponsors for transportation.

The family are a world away from the old reality - running from their home due to bombings, fleeing and then struggling to get by in Lebanon.

When the family arrived, they were "exhausted in a profound way", said Moulton.

"It is almost impossible to imagine what everyone must have been through. It's not a bad thing for them to have a little recovery time. Soon enough, the daily grind will be upon them."