Can you catch a killer using only teeth marks?

- Published

A Texas forensic science commission has recommended that bite mark evidence should no longer be admitted in court cases. How accurate is the science?

Warning: This story contains a graphic image.

David Wayne Spence was executed by the state of Texas in 1997 for the stabbing deaths of three teenagers in Waco, Texas.

One of the most damning pieces of evidence against him was the testimony of a forensic odontologist - or an expert in bite marks- who testified that a mould of Spence's teeth matched marks on the victims.

On 12 February, a relative of 17-year-old Jill Montgomery - one of the victims - spoke before the Texas Forensic Science Commission about the case.

"I personally never could believe or understand the bite mark testimony, and some of the rest of the family couldn't either," said the woman, who identified herself as Montgomery's aunt. "We wanted to believe we had the right people. We no longer believe [that]."

Not long after her comments on Spence's case, the commission voted unanimously to recommend a moratorium on the use of bite mark evidence in criminal court cases.

"It's unprecedented in the history of forensic science," says M Chris Fabricant, director of strategic litigation at the Innocence Project, which has been instrumental in calling the technique into question. "[Bite mark evidence] resulted in thousands of convictions, and at least 24 wrongful convictions and indictments."

Though it does not have the power to ban the use of the evidence, the Texas Forensic Science Commission is a highly-regarded body of scientists and attorneys appointed by the state's governor. It is expected that judges in the state will follow the panel's advice and that the impact will reach far beyond Texas borders.

"The implication now is that if anybody tries to bring bite mark evidence into the courtroom they're going to cite the Texas commission decision," says Peter Bush, an expert in forensic dentistry at the University of Buffalo's South Campus Instrument Center. "It's going to make it hard to present this evidence anywhere, in any state."

One of the earliest convictions obtained using forensic dentistry was a 1954 burglar who allegedly left his teeth marks in a piece of cheese. After a case in 1975, when a perpetrator made clear bite marks in the cartilage of a murder victim's nose, this type of evidence became admissible in courts across the country. The American Board of Forensic Odontology, external was established in 1976 to certify forensic odontologists.

Though the technique always had its critics, the beginning of the end came with the rise in the use of DNA evidence. A textbook case is Ray Krone, who was convicted and sentenced to death in 1992 for the stabbing death of a woman in a bar in Phoenix, Arizona. The only evidence against him was expert bite mark testimony.

In 2002, DNA evidence implicated, external another man and Krone was freed. The Innocence Project noticed how many of their DNA exoneration cases involved bite mark evidence, and have been highly critical of the technique since.

"People's teeth are not unique like fingerprints," says Bush.

He presented the Texas commission with the results of several of his studies on bite marks on fresh cadavers, which showed that not only does human skin distort the imprint in myriad ways, but that human teeth sets are actually more similar to one another than expected.

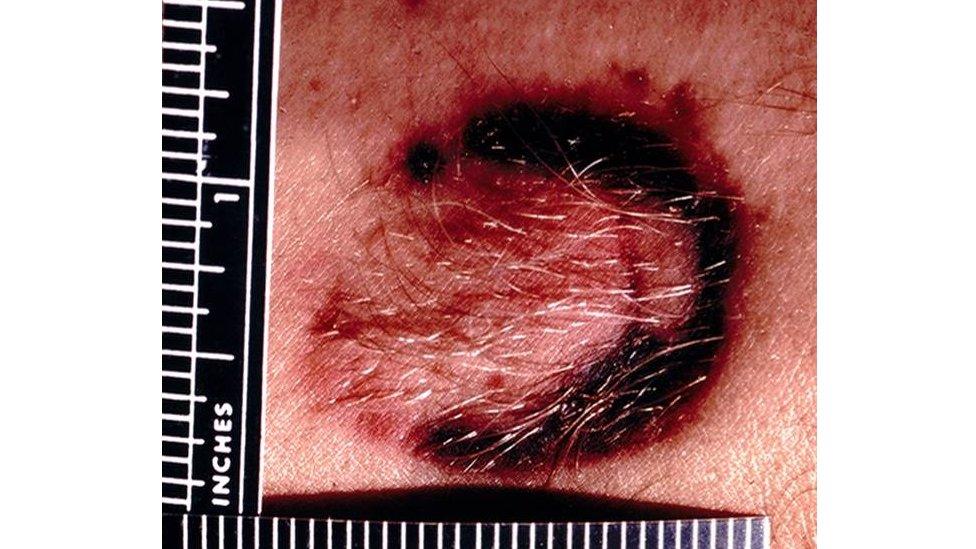

Bite mark used in the wrongful conviction of Steven Mark Chaney, the case that launched the complaint in Texas

The report that had the biggest impact on the commission's decision was one from a scientist who was once regarded as a proponent of forensic odontology. The study showed that 39 certified experts frequently could not form a consensus about whether or not a picture of a wound was even a bite mark, external.

However, the American Board of Forensic Odontology still stands behind the technique. Bite mark forensics are not only used for identifying perpetrators, they testified, but is also useful in child abuse cases to prove that bite marks belong to adult members of a household as opposed to other children.

"A complete moratorium on bitemark evidence in the court room would be a tragic mistake with innocent suspects and abused children no longer being able to benefit from bitemark analysis," writes Dr Gary Berman, president and chairman of the ABFO, in a message to BBC News.

"The ABFO is acutely aware of cases involving bitemark analysis in the past that have contributed to several individuals wrongly being convicted. This is not acceptable. It is the responsibility of the Forensic Odontologist when testifying in court to make known to both the judge and jury the limitations of bitemark analysis. This was not always done in the distant past."

Nevertheless, the commission determined that it is too risky to continue allowing the evidence into court, and asked the ABFO to return after it has conducted further scientific research on its techniques.

The commission will now begin auditing every bite mark conviction obtained by the state of Texas in the last ten years, including the case of David Spence.

"It's going to be an enormous undertaking that the Innocence Project will assist with," says Fabricant. "It should have stopped dozens of years ago, unless and until it can be scientifically validated."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.