Why is the UK still printing its laws on vellum?

- Published

The UK's law is on scrolls. In a tower

After a reprieve, the UK is to continue printing and storing its laws on vellum, made from calf or goat-skin. But shouldn't these traditions give way to digital storage, asks Chris Stokel-Walker.

Last week the House of Lords decided to end the printing of laws on vellum for cost reasons. But now the Cabinet Office is to provide the money from its own budget for the thousand-year-old tradition to continue.

Vellum lasts a long time. Dig into the archives of the UK's parliament and pull out the oldest extant law and you'll find a very old document. It was first inscribed in 1497.

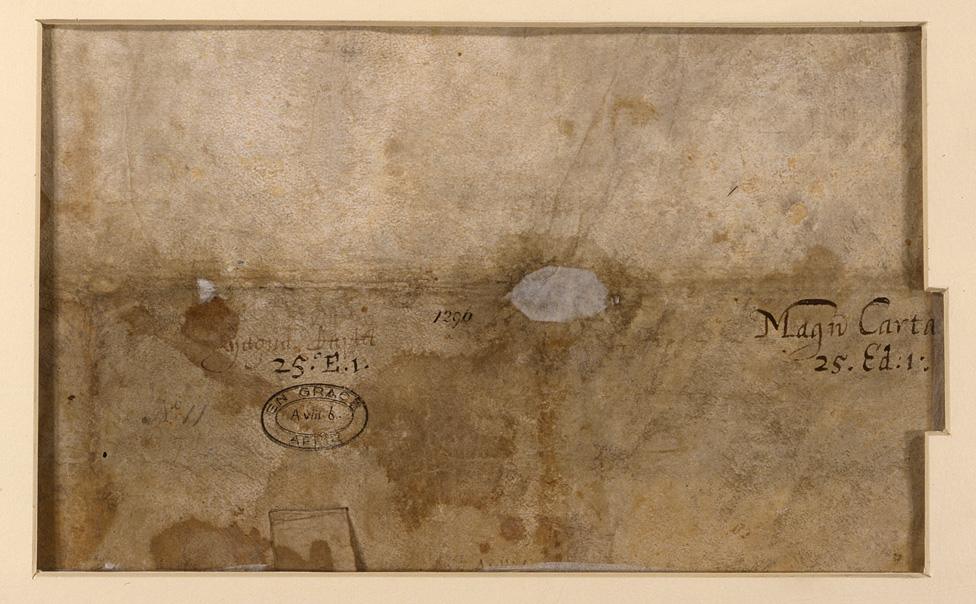

Over time, ordinary paper can deteriorate rapidly, while vellum is said to retain its integrity for much longer. Original copies of the Magna Carta, signed more than 800 years ago on vellum, still exist.

The Brudenell Magna Carta, document on vellum, dated 12 October 1297

The proposed change was a move to higher-quality archival paper. But are politicians missing the point?

Sharon McMeekin, of the Digital Preservation Coalition, an advocacy and advice group for digital recordkeeping, thinks so.

"People have been bemoaning the loss of history by changing to archival paper," she explains. "I think people are missing the point there. Truly representing the context and history in which these records were made require them to be kept in a digital format. It's more representative of the technologies and communication methods used today."

So why in the digital age do we keep physical records of documents at all?

There's a simple answer, says Adrian Brown, the director of parliamentary archives, who oversees a collection including 8km-worth of physical records of parchment, paper and photographs in the 325ft tall Victoria Tower at the western edge of the Palace of Westminster.

In the tower, scrolls of vellum are piled up in a vast repository, spooled in a range of different sizes, looking superficially much as they would have done hundreds of years ago.

"We simply respond to the way parliament chooses to create its records," Brown says. "In this case those are still going to be physical - though the proportion that is digital will increase over time."

But there are other reasons, too.

"In many circles there's still a real discomfort around digital archiving, and a lack of belief that digital can survive into the future," explains Jenny Mitcham, digital archivist at the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York.

The whole concept of digital storage is a relatively new innovation, and the path by which it could survive through the years is not clear.

"We don't have the ability to look back and say we know for a fact in 200 years time we'll still have this stuff," reasons Mitcham. "We can't prove that fact without a time machine."

What is vellum?

Vellum is made from calf-skin. The word shares its derivation with the word "veal" from the old French "velin" (Collins Dictionary) or "veelin" (Petit Robert).

Vellum is made by first soaking calf-skin in a lime wash, says calligrapher and illuminator Patricia Lovett. The lime causes the hair follicles to expand, making it easier to scrape fat and fur from the skin. This is done with a curved-bladed knife called a "scudder".

The prepared skin is then washed and stretched onto a wooden frame, and scraped further with a lunar knife to raise the nap and create a more even thickness. Finally the skin is left to dry; the length of time depends on the ambient temperature, humidity and the individual qualities of the skin.

Patricia Lovett, calligrapher, external

Watch vellum being made on BBC 4's Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings

There's an excellent example of how a digital archive can quickly run into problems.

Between 1984-86 the BBC Domesday Project engaged more than a million people from around Britain.

Children at more than 9,000 schools helped compile a statistical survey, personal thoughts and memories. The data was stored on special laserdiscs, then seen as a technology of the future.

Nearly two decades later, there were virtually no extant disc players able to read the specially formatted discs. After a lot of work, the data was made readable, but the case for digital archiving had suffered a setback.

"Examples like that imply that digital is more fragile than physical," Mitcham laments.

Mike Tibbetts, one of the two creators of the Domesday Project, wrote in 2008, external that "the fault in all this lies not in the lack of vision or foresight by the technologists but that, at least in the UK, the national systems of data preservation and heritage archiving simply don't work reliably or consistently."

This is the issue, according to Jenny Mitcham. Just as preserving a physical archive requires careful consideration of temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure to prevent paper from turning brittle and breaking, so digital archives need to be tended to.

"There's certainly truth in the fact that if [a] digital [format] is neglected, it'll become obsolete," she says. "But if it's brought into a digital archive, and that digital archive is well set up and knows what it's doing, migrating and actively managing files over time, the chances those files will be readable in the future are vastly improved."

Adrian Brown lists the difficulties in maintaining paper records - "decay, chemical changes that happen in the physical items; you've got insects and animal damage; the effects of temperature and light and humidity and dust. Tearing, rubbing, those kinds of issues."

But with digital, there are different risks. "One of the things about digital information is that it's not fundamentally human-readable," he explains. "You need some kind of technology to turn it into something understandable. Technology as we know changes very rapidly; what you can find is your way of turning those 1s and 0s into meaningful information can be threatened if you don't take precautions."

Lee Mapley of William Cowley Parchment Works works on a sheet of vellum

And, as anyone who has lost beloved holiday snaps to a hard drive failure knows, IT systems are far from infallible.

"With digital, the last thing you want to do is put it somewhere and leave it alone," Mitcham says. "There are things you need to do over time to make sure everything's OK with it."

Documents are migrated from one file format to another as old versions of applications become outdated. It's also necessary to check information hasn't been lost in the transition.

Backup copies are continuously made, and placed in different locations. Checksums, a process to make sure errors have not wormed their way into files, are run weekly.

So archives are indeed moving from pieces of paper to bits and bytes. The British Library keep a physical copy of every book, magazine and newspaper printed in the United Kingdom as part of the principle of "legal deposit", a law which has existed since 1662.

But since 2013, electronic records of websites, blogs, CDs and electronic journals have also come under the catchment of the legal deposit law.

Advocates point out digital records have their advantages over paper documents.

Metadata associated with electronic files can give an insight into the messy creation of a work, rather than a polished final document. It's sometimes possible to view how long someone spent typing up a record, and even to see what they changed between drafts.

And just as with 500-year-old vellum, there's history in our hard drives, too.

"I get excited by digital archaeology," Mitcham admits. "If you find a pile of 5¼ inch floppy disks, I get a buzz out of that. Being able to find out what's on those discs, look through old Wordstar files, and get an idea for how computing has moved on through time, that's fascinating."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.