What happens to the UK's least-used phone boxes?

- Published

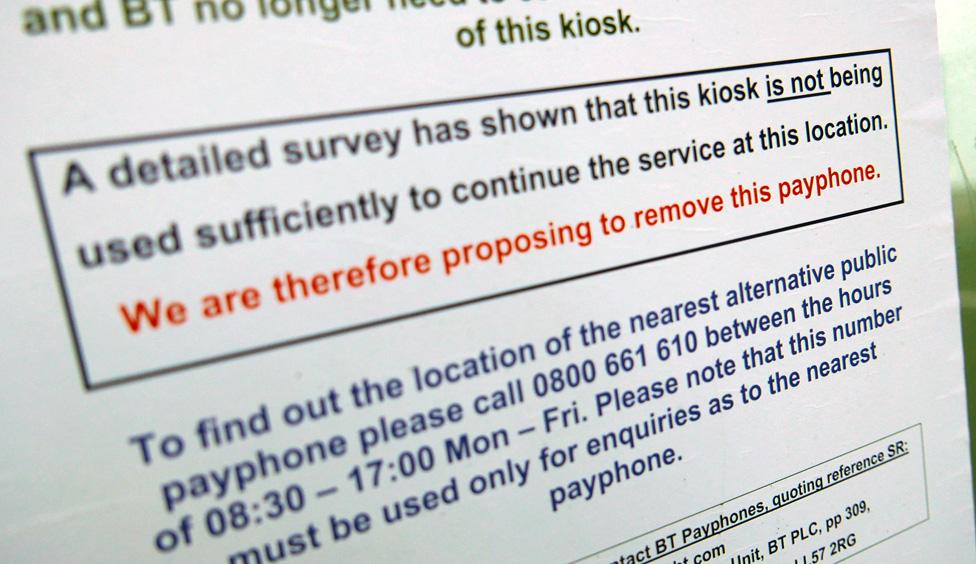

A phone box that is not much longer for this world

There are about 47,000 phone boxes on Britain's streets, according to BT, who run almost all of them. Soon, there'll be one less.

On Great Portland Street, near the BBC's Broadcasting House, a notice pasted to a steel and glass phone kiosk declares: "Telephone kiosk review. This kiosk is not being used sufficiently to continue service at this location."

It's no surprise that it's not getting much use. Someone has smashed the handset. You could dial a number, the keypad is still there, but no one would hear you.

With so many mobile phones around these days, perhaps it's a surprise that the number of phone boxes in the UK is still so high. Will they all be gone soon?

Phone boxes are strongly in our memories - coin-in-the-slot moments of joy and sadness, good news and angry goodbyes. And there's their impact on the landscape.

The man who makes the decisions on the future of the phone kiosks is BT's Neil Scoresby, who has the intriguing title "head of payphones and prisons".

How does he decide that it's time to pull a phone box out of the ground?

"It's normally based on whether there's still a demand for using the payphone. But we also factor in whether there's a mobile signal or whether the payphone is needed for any other social need, for example a suicide hotspot or at an accident blackspot location."

The statistics tell the story, says Scoresby.

"In the last 10 years, we've seen usage of payphones decline by over 90%. At the same time, of course, mobile phone adoption has gone the other way - so there's 93% adoption of mobile handsets."

Who in the UK hasn't got a mobile phone? After all, these days you can get one for £10. Who needs a payphone?

"There are some groups that don't have mobiles," says Scoresby. "The elderly; children make use of payphones; and also, when people's batteries go flat. Then they need to find a phone box."

That's why under Ofcom rules BT can't take out a phone unless there's another one within 400m. "If there isn't a payphone within 400m, then we have to consult with the council. If they object to the plans to remove, then the payphone stays," says Scoresby.

There's always going to be a phone box near the Severn Bridge, for example. Inside are displays of Samaritans advice and numbers to call to speak to someone who can help.

Prisoners do have a limited right to make phone calls, which means payphones. There are no coins or even phone card-type phone boxes now, Scoresby says. Instead there are calls earned through work and behaviour. Some prisoners are even getting phones in their cells.

There is one question that Scoresby is reluctant to answer directly: "How little is too little when it comes to money earned from calls from a payphone?" There are too many variables, he says. For example, is it vulnerable to vandalism and therefore expensive to keep going?

If you want to keep a particular phone box, but BT say it's not paying its way, what could you do?

Some might put themselves bodily in front of the truck that's come to uproot it. That's what Nick Rogers, publican of the Surrey Oaks pub near Dorking, did when they came for the box across the road.

"A BT truck turned up one morning with the chains ready to hoist the phone box from its site. It seemed like a real shame to lose the phone box from the village, it's been part of the village scene for so many years," he says.

Rogers made a call to the parish council and discovered that for £1 you could adopt a phone box. But it takes a lot of paperwork. "To buy us some time, while the chaps went off for their tea break, I obstructed the phone box with my car and prevented them from getting any further with the chains."

Rogers got his way. The box is still there. Without a phone, though. Soon it will house a defibrillator - "a heart start machine", Nick calls it. "This is a busy road, there are accidents, and the emergency services and the community will have this resource," he says.

You can get commercially ambitious with your local phone box, if you like. Edward Ottewell of The Red Kiosk Company, based in Brighton, negotiates with local councils to get planning permission for change of use. Then the phone box can become a coffee stall or ice cream shop. "Recently, we've had someone that wants to do a movie photo booth," he says.

Vicki Hoilett, originally from Washington DC, is now selling souvenir models of Big Ben, London buses, Beefeater teddies - and little red phone boxes - from a phone box she's rented near Lambeth Bridge, across the Thames from the Houses of Parliament. "It will still look like a phone box, nothing will change, because I don't want to take away from an amazing design," she says.

It seems like the phone box will survive.

More from the Magazine

The red telephone box is a much-cherished symbol of Britishness. But most have been removed from the nation's streets, with more due to disappear. Where do they all go?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.