Giving names to online harassment

- Published

A new online resource has been published by the Women's Media Center (WNC) to help people identify the different forms of online abuse against women. Will it make a difference?

In her first year of graduate school, Lauren Rankin - now a writer and women's rights advocate - wrote an article for a local blog. Describing the article as "dinky" - so much so that she can't even remember the topic - and expecting it to go nowhere, she shared it on Twitter with her few thousand followers.

A few days after publication, she noticed something was wrong. People began bombarding her graduate school searching for her contact information. Her personal information and address were shared online, and she received an escalating number of death threats. She discovered a message board site, 4chan, had picked up the piece and a group of anonymous users had co-ordinated an online campaign against her.

She is still unsure why she was targeted.

It was at this point she called the FBI.

"You learn very quickly if you're going to be a woman, especially if you're speaking out on women's rights, you're going to be attacked," says Rankin.

Although the FBI did circle back to check she was safe, they were unable to find any leads to take legal action.

The more well-known she became, the more Rankin endured instances of co-ordinated online campaigns, rape and death threats, and online stalking. Despite blocking sites or users that abused her, duplicate accounts would appear, and she was anxious these digital attacks would materialise in real life.

Overwhelmed, she felt she had no option but to significantly reduce her online presence.

"I had to take a break. I go days, sometimes weeks without tweeting and I don't really write publicly anymore. The way that I am an advocate has changed. I don't like to think that I cowered to my fear, I just prioritised my own wellbeing."

She's not alone. In a 2015 UN report, Cyberviolence Against Women and Girls, external, they found that 73% of women have been exposed to or experienced some form of online violence.

Now the Women's Media Center, external has released an "Online Abuse 101" guide detailing the complex and unique ways women may face online abuse.

It acts as a encyclopaedia for tactics used against women online, explaining the nuances of attacks ranging from flooding users with negative comments or virtual stalking, to revenge porn and identity theft.

Women may face doxing, where hackers release personal information or financial details to cause fear or panic. Others users may endure cross platform harassment - where a single user is targeted across their various social accounts - or face grief trolling, where attackers use images or names of lost ones to create fake websites or memes.

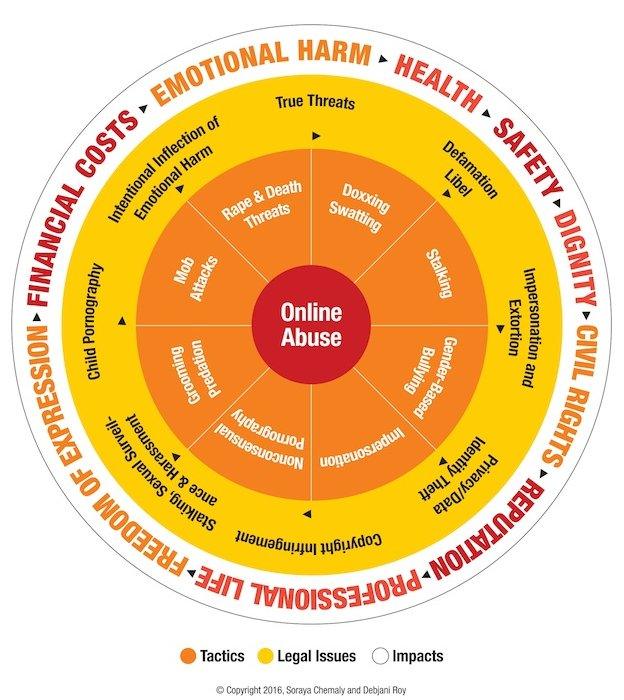

They have also developed a wheel to help visualise the problem, with online abuse at the centre. The first circle maps out the tactics used, with concentric circles fanning out to show how this corresponds to legal issues and finally, how this psychologically affects the victim.

The WMC hope to show that harassment isn't an single issue, but instead a collection of specific tactics that are often employed simultaneously. As a result, the WMC hopes online platforms can create more effective protective measures and law enforcement can learn how to tackle this new frontier of digital crime.

Soraya Chemaly, director of the project, told the BBC, "the entire project was born out of necessity".

Soraya Chemaly, right, says the project was a "necessity"

"When I started to investigate, there was no proper understanding of what harassment entailed. People think about bullying or name-calling, but those aren't necessarily the only tactics we're talking about."

When women step forward to report online cases of abuse they are often trivialised or dismissed as "not real, not a problem," she adds.

Danielle Citron, a law professor at the University of Maryland, has specialised in cyber law and advised social media companies on how to shape their policies on abuse or harassment. Describing the project as "incredibly important", she says it is particularly encouraging as a means to educate law enforcement.

"The problem is people come to them, they're great with street crimes, but tracking down a poster is foreign to them. I'm not criticising them, but we need education."

She adds that although social media platforms have come a long way in providing protective measures, it's often unclear just how many ways users may be vulnerable, and this new language will help prevent trivialisation or misunderstandings between users and those who can help.

For now, Citron believes this is a promising moment for users, platforms and authorities alike.

"It's baby steps. At the moment many people don't understand what harassment means, it's too loose. It's important to have a set of definitions, and if we can get that right you can change social attitudes."

- Published26 November 2015

- Published25 November 2015