Inside the topless sisterhood

- Published

As a young dancer with feminist tendencies Bee Rowlatt was scandalised to find herself on stage alongside topless dancers. Many years later, after writing a book about early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, she visited the Moulin Rouge in Paris to talk to dancers who bare their breasts in this unforgiving industry. And, as she describes here, she wavered.

The French writer and artist Jean Cocteau had a fondness for Moulin Rouge showgirls. He called them the "caryatids of that great and marvellous epoch that was ours". But maybe Jean Cocteau never had a thong heaved up his bum or got shoved over on stage, because these are my memories of showgirl life.

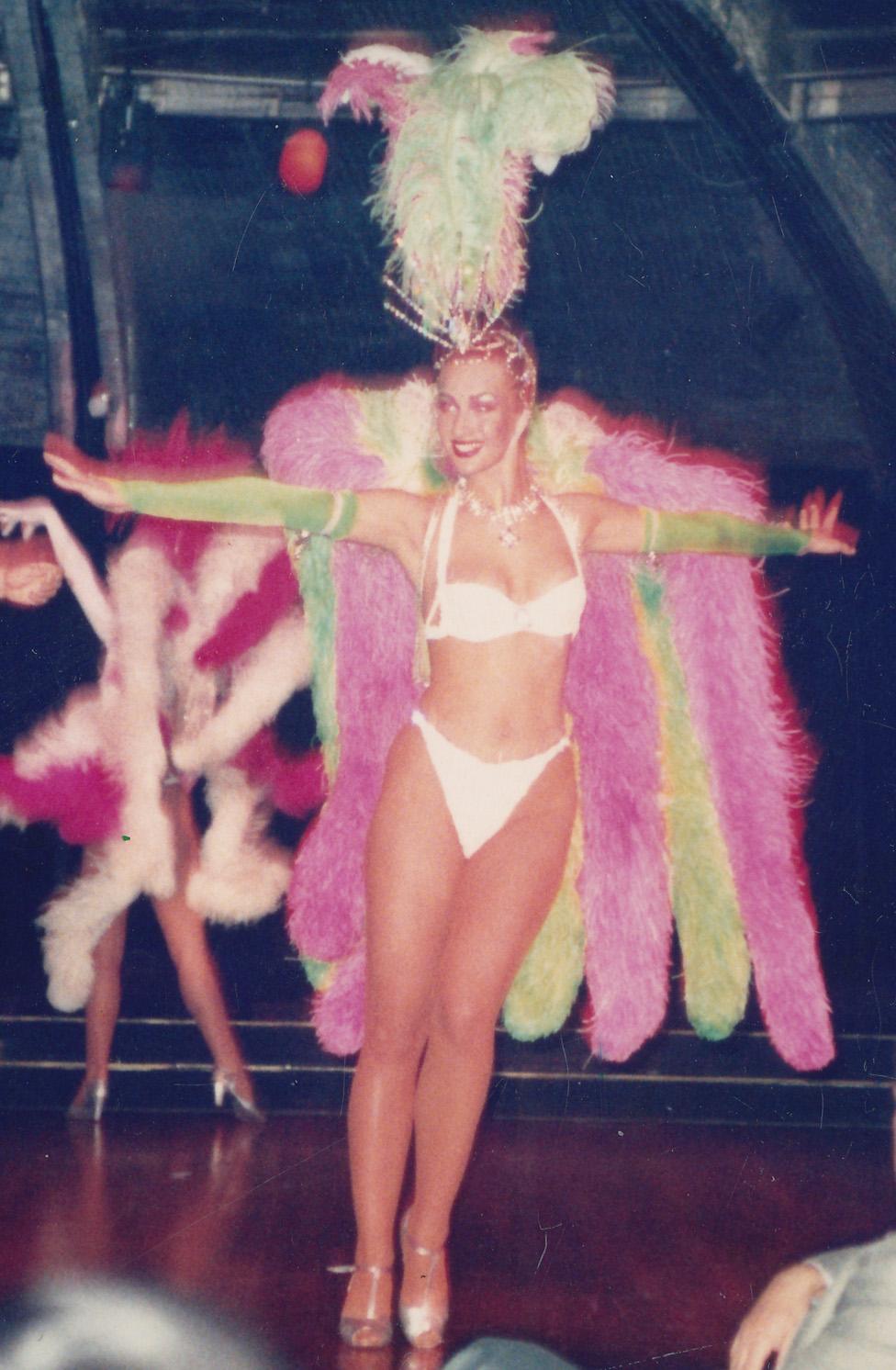

I was only a teenager when I landed my job at the Isla del Lago show in the Canary Islands. Until then I'd been a dedicated ballet girl with a growing tendency for feminist indignation and had no idea what I was getting myself into. The show was a high-kicking parade of gigantic feathers and eyelashes. But what the audience saw was nothing compared to the antics backstage.

Bee had to learn the showgirl code quickly

This was show-biz, red in tooth and claw - the survival of the thinnest and meanest. As the youngest recruit I had a lot to learn. I couldn't dance in those cursed silver high heels, or even wear a thong properly. And to my horror, some of the dancers were topless. A proper dancer shouldn't have to expose her breasts, I fumed. It was a line I refused to cross. The whole experience was like falling into a parallel universe. Somewhere glittery, but very very hard.

A week into rehearsals I still couldn't dance in heels. A very tall blonde took me to one side. She was an old hand, known to all as Aunty Debbie for taking new dancers under her wing. She warned me to ignore the blisters and keep the shoes on at all times: the gossip was that I was useless and might get sacked. There was only one way to survive. I pulled the shoes on and limped straight back on stage.

Luckily things got better quickly. I learned about "weigh day", when dancers were lined up and weighed one after the other, how to keep sweat out of your eyelash glue, and how to make tampon strings invisible. I learned to sleep during the day, not to get suntan lines, not to eat or drink before the show, and never not ever to get in the way of the principal dancer during a quick change. When I finally nailed the high kicks in high heels, I was there.

Bee and Debbie backstage

We spent long hours in the sequin-strewn dressing room, our reflections surrounded by light bulbs. Night after night we sat around, semi-naked, sewing our tights, and baring our souls. Bad boyfriends, tricky childhoods, diets, same-sex encounters, abortions, boob jobs gone wrong - we discussed it all.

These were tough, hard-working, independent women. None of them was stupid. Yet I was stunned by what they deemed acceptable in life - had I been so sheltered until now? We were a room full of hungry women on low wages, who had endured public weighings and been called bitches and "fat cows on ice" by our employers. Why did we put up with it?

Years later I tracked down Aunty Debbie again while writing my book In Search of Mary, about the foremother of feminism. Our reunion began with a sly appraisal. Whenever two former dancers meet, a certain canine-style moment must come to pass, as they discreetly check out each other's bums. (Has she got fat?) All ex-dancers fear the critical gaze of another ex-dancer. We pretend we don't, but we do.

Debbie and Bee in their high-kicking days...

... and today, sizing each other up

Soon it was all laughter and memories. But Debbie's tales of backstage bullying put mine in the shade. Jealous colleagues sabotaged her quick costume changes, and even worse, she had regular spinal injections to mask injuries.

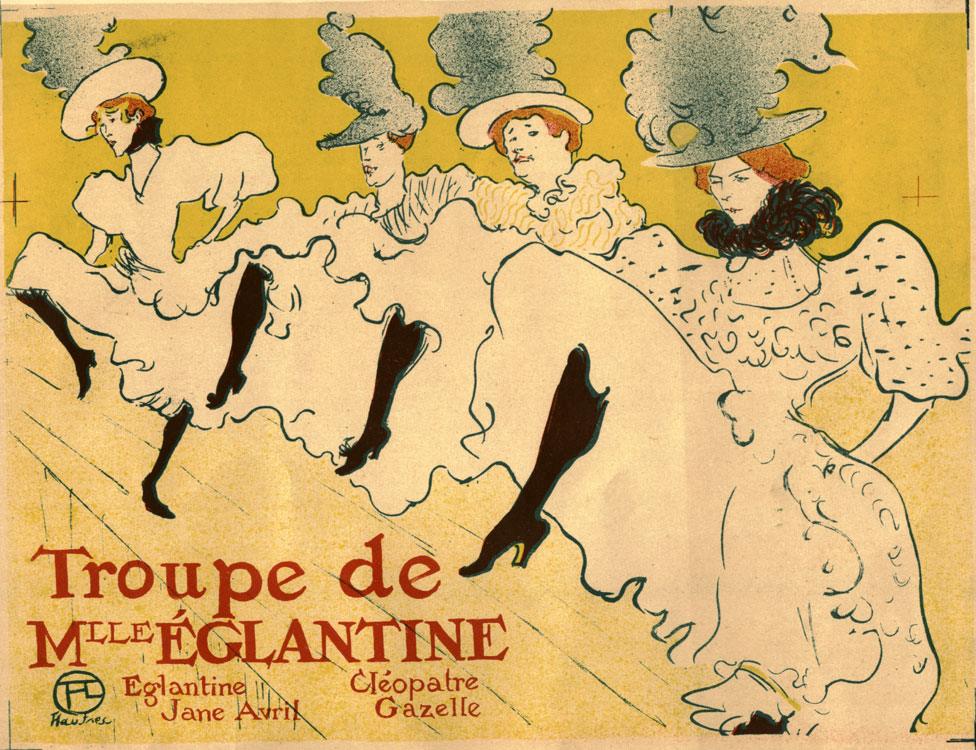

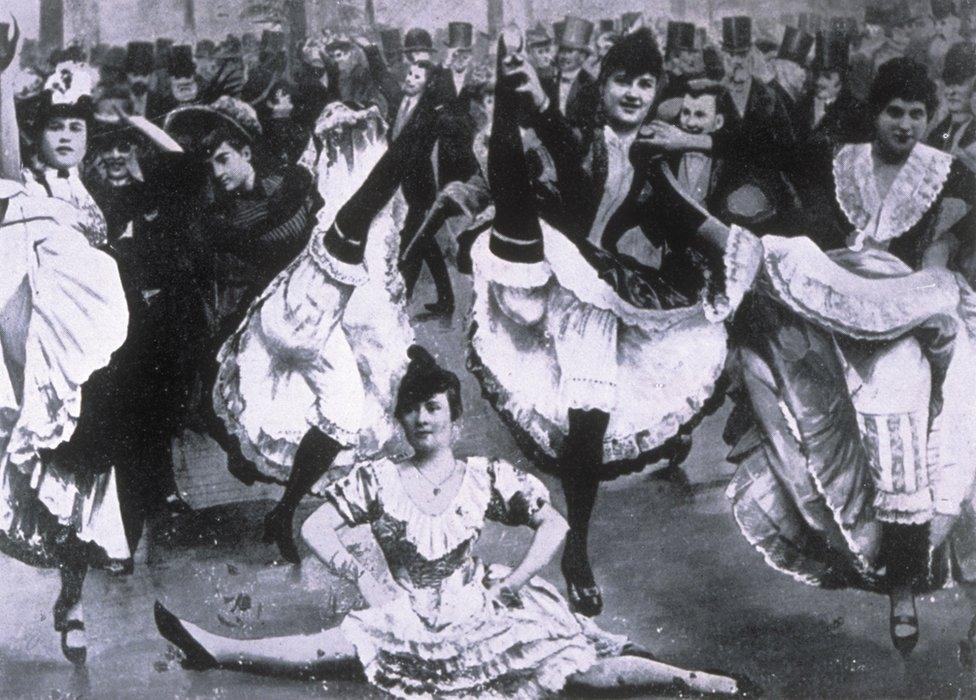

We decided to visit the Moulin Rouge, where Debbie first worked as a 16-year-old rookie. This legendary Parisian establishment was the birthplace of the can-can, immortalised by Toulouse-Lautrec and still the Moulin's signature routine. An early edition of the Oxford Companion to Music calls the can-can "a boisterous and latterly indecorous dance, exploited in Paris for the benefit of such British and American tourists as will pay well to be shocked".

Can-can dancers as portrayed by Toulouse Lautrec

Another definition? It's every dancer's nightmare - the most dangerous, demanding and injury-prone number of them all. Debbie described bloody noses, ripped tendons, and the notorious split-jumps. "We'd leap up into the air, throw our legs out into the splits, then land on the floor in that same position. No wonder we all screamed throughout!"

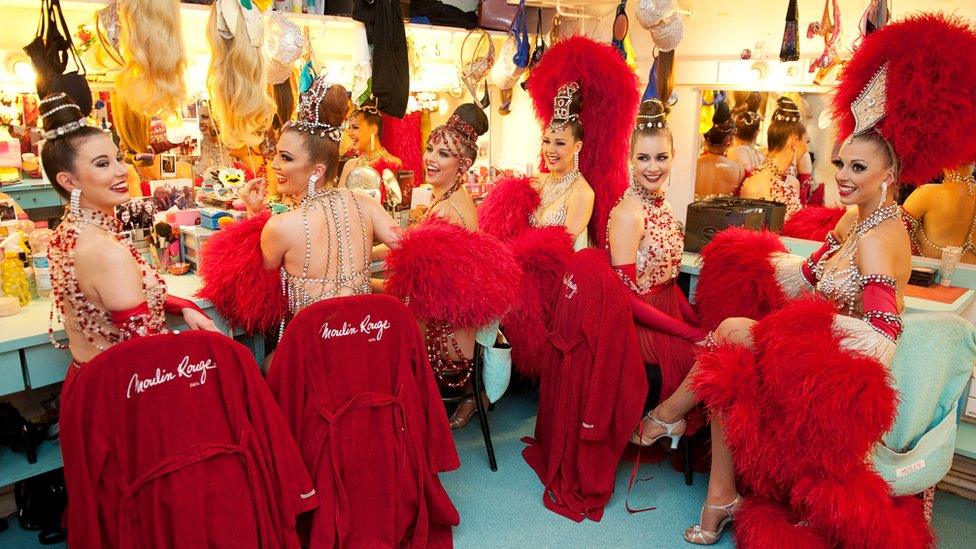

We arrived at the Moulin and were led backstage into the very heart of sequin-land. Rows upon rows of costumes and headdresses swung from pulleys up on high. Gigantic red and pink feather edifices waved like a coral reef. Between them flitted a shoal of huge-eyed and pale-limbed dancers. They were like beautiful aliens. I'd never been to the Moulin before, but I recognised this world at once.

One of the dancers, Katie, had recently returned from a can-can related injury. She had been hired five years ago, she told us, in an audition attended by 300 girls. In our day, auditions were likely to attract 30 or 40, and the dancers were mainly British, whereas today the talent pool is completely international.

But while standards may have have risen, apparently tyranny levels have not. When I told Katie about weekly public "weigh days" she nearly fell off her chair with shock. "No! They'd never do that here. Obviously we have to stay in shape. If that changes they take you aside and talk to you. But not publicly!"

I tried to dig deeper for evidence of exploitation, and this time Debbie cut in, emphatically: "Working at the Moulin was the best thing that ever happened to me and the truth is I would've done it for free."

"It's a privilege to be here," agreed Katie. "Being a dancer means everything to me. I feel I can be me, I feel amazing."

But why should dancers go topless?

Katie smiled diplomatically. "I know it's not for everyone. But it actually gives dancers more status," she said. Then she and Debbie exchanged a wink "and it gets you out of the can-can!"

"Status?!" I echoed.

Bee drew the line at topless dancing but Debbie enjoyed the status it gave her

"Same in my day," said Debbie. "We topless girls were higher up the food chain, with different choreography - it was a promotion." She squeezed my knee affectionately. "You guys were just chorus line!"

"Anyway," said Katie, "a lot of people change their minds when they see the show." I quietly resolved not to change my mind.

Just before the curtain lifted, I whispered to Debbie, "I still dream about that curtain moment." The recollection of the feeling of performing on stage was almost painful. I held my breath, and it began.

The show was a shimmering, delirious, timeless piece of joy. There were moments of camp and kitsch, of course, but what other night out can boast thousands of euros' worth of feathers and rhinestone, 800 pairs of handmade shoes, 700 silver champagne buckets and five live pythons?

The dancers themselves are creatures so beautiful that they catch your breath. They're like statues come to life. There's a silver-screen nostalgia about the spectacle, and the can-can, in all its unhinged glory, sent the audience wild.

"At the Moulin we respect the traditions," said Thierry Outrilla, a former dance colleague of Debbie's who is now the stage director. "There's a certain magic of things, and you cannot change that."

The show ended but somehow we couldn't bear to leave. The conversation returned to breasts: to cover or not to cover. Annoyingly, Katie was right. Seeing the show did change my mind. There was no grinding and no jiggling, it was a remote kind of beauty, a thousand miles from twerking. It was as old-school as a nude statue.

As the waiters began to stack chairs around us, I had another realisation: there was solidarity among dancers, a showgirl code. If you could get through the agony, you became family. After all, here I was, with the woman who stuck up for me 25 years ago. There was true sisterhood behind the sequins, and if today's Moulin showgirls are anything to go by, that's still the case.

The heart of sequin-land

"Let's face it," I said. "These dancers are healthier, they work harder, and they're less bitchy."

"They're just better than us," sighed Debbie.

"Well thank goodness we're old and can still behave badly!" we cackled. I indulged in a champagne-fuelled reassessment of my negative memories. They had been bathed in the spotlight of my political views, to the neglect of some of the inexplicable magic.

How could I have forgotten this? Being a dancer is a short-lived, fragile joy - a temporary and precious triumph over gravity. Perhaps it would make sense to invest those training years in a guitar or some other entity that never gets injured or old. But we invested in our own bodies. And that, for a short time, was like being able to fly.

Everyone from Rumi to Nietzsche extols the power of dance. The American choreographer Merce Cunningham knew the truth. "You have to love dancing to stick to it," he said. "It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold, nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive."

Listen to Bee Rowlatt and Debbie Gills discussing their experiences as showgirls and visiting the Moulin Rouge on Woman's Hour, on BBC Radio 4. Bee Rowlatt is the author of In Search of Mary, the Mother of all Journeys.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.