Museum of Lost Objects: The Temple of Bel

- Published

Few of the excesses of the group that calls itself Islamic State have transfixed the outside world as much as its destruction of Palmyra, the ancient desert oasis city in central Syria. Palmyra's remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in August 2015.

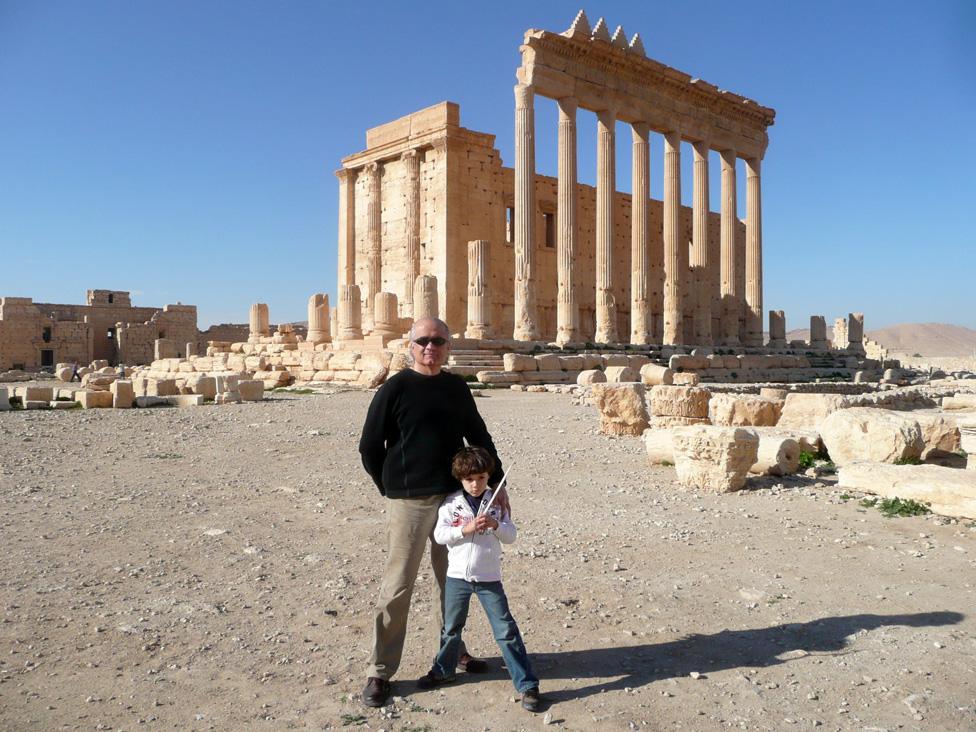

It looked in many ways like a great Greek temple. Standing in the middle of a walled sanctuary, the rectangular structure had once been ringed by towering 15m-high columns - Corinthian columns, topped by carvings of acanthus leaves. Some of these still stood, two millennia later, before IS blasted the temple to bits.

There were differences from the familiar Greek design, though. The roof had been decorated with stone triangles, or merlons, that ran along its edges like rows of giant, pointy teeth. And the entrance wasn't quite where you might have expected it to be. In most classical temples the door is on the short side of the rectangle and leads to a single altar, but in Palmyra the main entrance was on the long side.

"Inside you have to turn either right or left because the temple had two altars," says Nasser Rabbat, a Syrian art historian who in the 1970s lived for a while in a house inside the temple compound. "There are multiple gods that are being worshipped in there."

Two thousand years ago, Palmyra was a key oasis on a desert trade route that linked the Mediterranean world with lands to the south and east. It grew rich from this trade, and was strongly influenced by its trading neighbours.

Find out more

The Museum of Lost Objects traces the stories of 10 antiquities or ancient sites that have been destroyed or looted in Iraq and Syria

Listen to the episode about the Temple of Bel on Radio 4 from 12:00 GMT on Tuesday 1 March or get the Museum of Lost Objects podcast

Read Museum of Lost Objects, No 1: The Winged Bull of Nineveh

The culture that developed was "Arab in origin but then classical in influence and in temperament and inclination" according to Rabbat, who likens Palmyra to Petra in Jordan. Both, he says, are "a mark of how cultures can come together creatively".

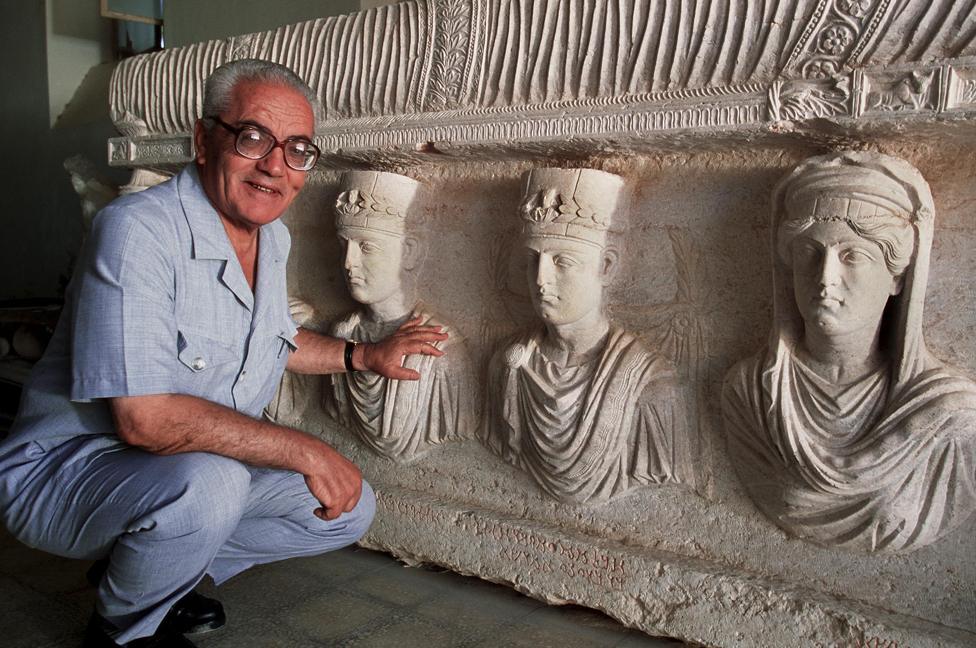

One detail of the temple Rabbat points to as a good example of this mingling of cultures is a frieze showing a funeral procession.

"There are three women carved in a very abstract way, as if they are clad in togas but they are wrapped from the head all the way to the bottom. They're dressed like a classical woman, but these are Arab desert-based women and their heads are covered," he says.

"The artist has done it with flowing lines that are extremely sinuous... What you see is something that is very geometric, but immediately evocative of the image of a bunch of women walking together."

In later years, as Christianity spread across the region, the temple became a Byzantine Church, and then with the coming of Islam, a mosque.

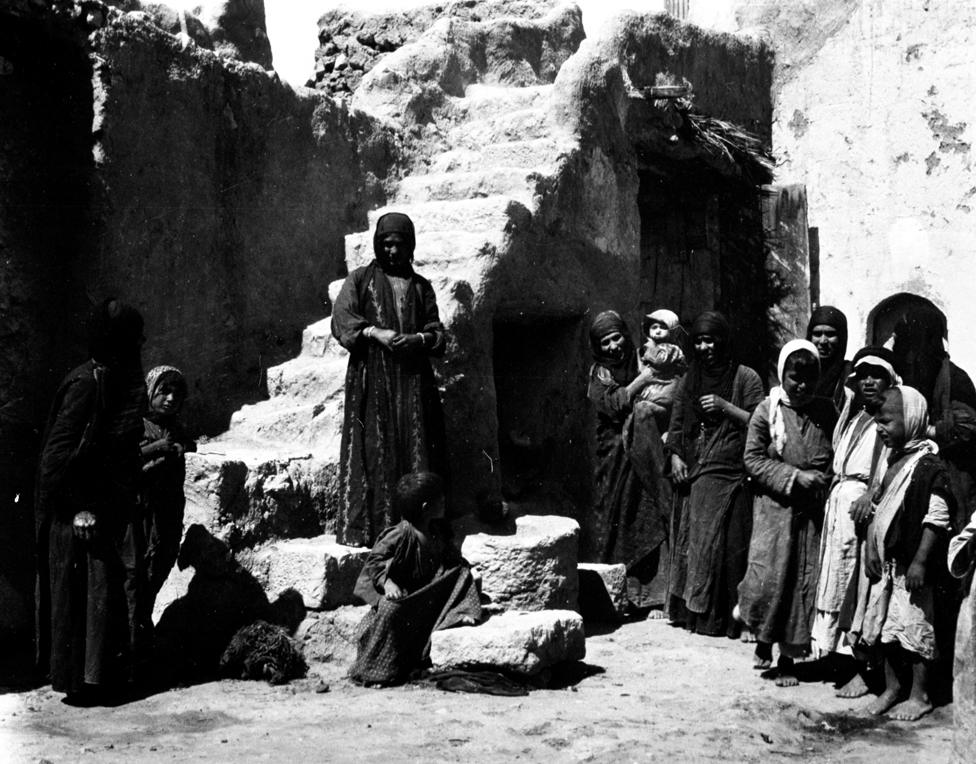

By the early 1900s, Palmyra had been a ruin for centuries, but parts of it were still inhabited. Some old buildings were used as shelters by herders and nomads, while the compound of the Temple of Bel had become a small village.

"People were integrated in this fabric of inhabited heritage," says the Syrian archaeologist Salam al-Kuntar from the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

"I have a special love for Palmyra because the Temple of Bel is where my mother was born.

"My grandfather was a policeman serving in Palmyra and my grandmother wasn't even 20 years old when she got married and moved to Palmyra. The Palmyrene women taught her how to make bread and cook. I hear many stories about the building, how people used the space, how children played around, including my mum. So that's what it means to me. This is the meaning of heritage - it's not only architecture or artefacts that are representing history, it's these memories and ancestral connection to the place."

When IS destroyed the temple in August last year the main entrance arch remained standing - the only part that survived.

Satellite images show Palmyra's once majestic Temple of Bel before and after its destruction by IS militants

For World Heritage Day in April 3D-printed replicas of the arch will be erected in Trafalgar Square in London, and Times Square in New York.

Zenobia's story

Another illustration of Salam al-Kuntar's point about heritage being bound up in memories and lived experience, is the story of Zenobia al-Asaad, whose father, the archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad, was head of antiquities at Palmyra for 40 years.

When Zenobia was born, her parents named her after the Palmyrene queen who led a rebellion in the 3rd Century AD against the city's Roman overlords, and carved an empire that stretched from modern day Turkey to Egypt.

"My dad wanted to give me and my sisters the names of special Arab women characters - especially those that he admired. One of my sisters is called Fairouz, after the Lebanese singer. But I like to think that Zenobia was the most special for him!" says Zenobia.

"So, yes I'm really proud of my name, very proud. Even when I was at school I remember feeling almost sorry for my friends that I've got this lovely name while they all had their normal names! But really, what makes me most proud is that my name was chosen by my father. And my name will always make me think of him.

"When I was a little girl, I remember sitting in the car with him, driving from our home in the modern part of Palmyra over to the ancient sites. We would walk around together, checking on things, laughing, talking, and the way he talked about Palmyra made me love the city even more, because I know he loved it. He would explain what some of these things once were - this was a temple, this was a tomb, this city was the place where Zenobia was from, who I'm named after."

Khaled al-Asaad had devoted his life to the study of the city, from its Roman-era tombs to the Temple of Bel. He and his daughter were both living there when IS - known as Daesh in Arabic - arrived in 2015. While many fled, he chose to stay.

"The day Daesh came to Palmyra feels like a blur, a dream, or nightmare. I remember being at home and I saw my neighbours and people, just running, the streets were in chaos. And they said, 'Daesh are coming to Palmyra they're barely a few miles away.'" Zenobia says.

"I told my father who was in his own house, 'You have to move, you have to leave with us,' and he said, 'No I don't want to leave, I was born in this city and I will die in this city.'"

During the chaos, Zenobia's husband Khalil Hariri and her brother Mohammed - also archaeologists - managed to load about 400 antiquities on to trucks. As they were leaving, they came under heavy gunfire from approaching IS fighters, which prevented Zenobia and her 15-year-old son from jumping on board.

Jeremy Bowen speaks to two of Syria's "Monuments Men"

She fled on foot with her son. However, with nowhere to go and armed with only her ID card, she soon returned.

"I went to my house and this Daesh [IS] fighter opened my own front door and refused to let me in. Around 10 other men turned up. I thought I was about to faint but my neighbours were with me, they were supporting me. I told the Daesh men, this is my house, can you at least let me get my wallet. They said, 'We can only give you your wallet if your husband will come and pick it up.' My husband wasn't there and so my son and I were homeless.

"But I wasn't scared and I was determined to get my house back. This was my home, how dare they take it! So in the morning I would go to my house and sit on the pavement in front and look at it, just watch them inside my house, walking in and out with their guns, like it was just a hotel for them.

"There were maybe 40 Daesh fighters inside my house. I would knock on the front door and ask for my things but there was always an excuse. 'We don't know where the Emir is,' or, 'The Emir is sleeping, we have to wait until he wakes up.' Under the new Daesh rules, women couldn't walk by themselves so my son went everywhere with me.

The so-called "Beauty of Palmyra" bust was discovered during excavations in Palmyra, by Danish archaeologist H Ingholt, in the 1920s

"Being in Palmyra during that time was just horrible. When Daesh would kill someone, they would leave their corpse rotting in the street for three days so everyone could see. And I would wonder who this person was and who their family was and if they had to walk down this street too.

"The only person able to console me was my father. I was crying, and I remember my father telling me in his gentle voice, 'Don't worry, as long as you are fine, as long as your son is fine, this is the most important thing. Houses come and go, money comes and goes. It doesn't matter. Family is what matters.'"

After a few weeks, Zenobia and her son managed to leave Palmyra and join the rest of her family, but her father stayed.

"He told me to take care of my children. And I remember him saying that if I ever needed anything that he'll always be there. He told me to stay strong for my family's sake. He told me 'I need Zenobia back, Zenobia the strong one, the one that I know.' And these were his last words to me."

Khaled al-Asaad was eventually arrested by IS.

"Those days were just awful. Every time the phone rang I wanted it to be him, or my brother saying, 'It's OK, our father is fine, he's free.' I can't describe this feeling, like hope and despair all mixed up in my heart. Then on the 28th day my brother came, and he was crying and all he said was, 'He's gone.' He didn't go into details and he didn't tell us how our father had died."

IS fighters executed Khaled al-Asaad in public in August. They hung a placard around his body accusing of him being an "apostate," a "director of idolatry" guilty of attending "infidel" academic conferences.

"And then all I wanted to know were his last words. What did he say, what did Daesh say to him, did they insult him? What we later heard was that my father - true to character - was calm, and his last wish was to see the city. Then they brought him back to kill him. Apparently he read the Koran quite loudly, and he was smiling, and this upset Daesh, they didn't like that and when they told him to kneel, he refused.

"I can't explain why I wanted to know these details, I just wanted to know what he went through. I remembered those unknown dead, beheaded people I saw on the streets of Palmyra, thinking, 'Oh my God, what happened to this person, I feel for their family.' And imagine, now this had happened to my own father. He was beheaded and his body was left outside for everyone to see. We don't even know where his remains are.

"The person most affected is my mother of course - but she tries to be strong. We don't want to feel weak, but I cannot really deny it, life is not easy. There's no peace inside me, but whenever I cry, I remember my father, I see him in front of me and his image is what gives me hope. He taught us to be strong and this is what I always want to remember.

"Believe it or not, I can't stop thinking about him, everything about him, his laugh, he had a really kind heart and playfulness, just like a small child. I think a lot about his touch, his hands, I imagine him sitting at home at the dining table. Whatever I tell you now I won't be really saying everything I think about him, because I can't explain my feelings, there's just too much. I remember his white hair, his eyes, and as I tell you about these things I can feel there is fire inside my heart. My heart is too full."

Now in Damascus with her mother and husband, Zenobia does not want to return to Palmyra. The destruction of its old stone monuments is forever linked with the death of her father.

"Palmyra the ancient city will always be a part of me, but I can't really imagine going back to Palmyra walking along the paths, looking at the sites without my father, he's the one who made us love this place.

"Just like the palm trees in Palmyra, where they really stand strong, rooted in the city, my father will be the same, he will be like these palm trees in Palmyra, rooted in the grounds of the city, always connected to the city and to us."

The Museum of Lost Objects traces the stories of 10 antiquities or ancient sites that have been destroyed or looted in Iraq and Syria.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.