Harvard drawn into race battle at US universities

- Published

Harvard's campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Harvard will no longer call its dormitory leaders "house masters". It is the latest controversy in months of protests at US universities about the legacy of slavery.

The decision by Harvard to use the term "faculty deans" to describe the lead advisors of student dormitories, instead of "house masters", is to do with the word's reminiscence of slavery in the US.

Harvard is not the only Ivy League school to dispense with "master" in some academic titles. Yale and Princeton have discontinued its use, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology is considering, external a similar change.

So is the word "master" - which has its roots in the Latin term "magister", a term for a scholar or teacher, and is found throughout academia from the title of "headmaster" to earning one's "masters degree" - offensive or inherently racist? Or is this, as one scholar dismissively put it, "PC nonsense, external" run amok?

Harvard's Mather House faculty dean Michael Rosengarten - formerly known as the house co-master - doesn't think so.

"We've opted for what we feel is a more appropriate title for this time and place. And it's mainly because a lot of people do associate 'master' with a master-slave relationship, which we don't feel comfortable with," he says. "We're very sensitive to racial diversity at the university. Anything that could be considered to be disrespectful of minorities becomes a problem."

After all, while the title "house master" at Harvard doesn't have historical ties to slavery on the campus, plenty of other parts of the university's history do - as is the case at many of America's most hallowed universities.

"Most of the time we have an image when we think of slavery, unfortunately that's that everyone worked and lived on a plantation. We don't think about the fact that churches and businesses and colleges and universities owned slaves," says Jody Allen, a visiting professor of history at William and Mary. "It's not in the textbooks."

William and Mary, for instance, "owned and exploited slave labor from its founding to the Civil War", external. Georgetown's Jesuit founders owned slaves in the 1700s. Three Harvard presidents were slave owners and the official seal of the Harvard Law School features the coat of arms of the Royall family.

"There's just something to the stories we choose to tell," says Rathna Ramamurthi, a second year law student and member of Reclaim Harvard Law. "[The Royalls were] a particularly brutal slave owning family, a family that violently oppressed slaves, made all of their money off the backs of slaves."

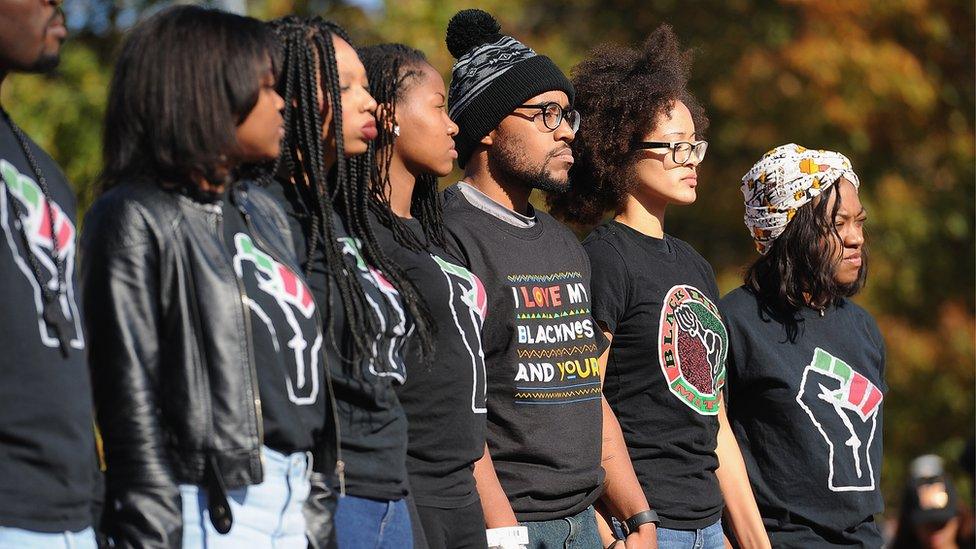

Student protesters at the University of Missouri

In 2001, Yale celebrated its 300th anniversary and its ''long history of activism in the face of slavery'', external. But critics pointed out that buildings on campus were named for slave traders and some of the university's earliest financing was derived from plantation profits and slave auctions.

Many credit former Brown University president Ruth Simmons - the first black president of an Ivy League school - with kicking off one of the first rigorous examinations of the school's link to slavery in 2003. The Brown family, a steering committee found, were "not major slave traders, but they were not strangers to the business either".

However, Craig Steven Wilder, a professor of history at MIT and author of Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities, says much of the institutional introspection ended in the early 2000s.

He says the continuing conversation about the legacy of slavery on campus has been stirred by the current activism of students - in part inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement - and not by the institutions themselves.

"It's been the student protests on campus that have been informed by students' own experiences," he says.

Diversity on campus has long been a problem, from the low rates of graduation for black students as compared to their white peers, to the higher average amount of debt African American students graduate with. While African Americans are enrolling in institutions of higher learning in increased numbers, the number that end up at so-called top tier colleges has dropped since 1994, external.

Activists says those disparities bear themselves out in incidents of racism on campus, like the alleged use of racial slurs at the University of Missouri , externalthat sparked nationwide protests and eventually lead to the resignation of the school's president. That flashpoint led to movements like the #StudentBlackOut protests and resulted in dozens of demand letters, external levelled at university administrations, like the one at Harvard that first asked , externalfor the end of the "house master" title.

The former Mulledy Hall at Georgetown University, named for Thomas Mulledy who sold slaves

Since then, demands to change symbolic vestiges of racism and intolerance have intensified and administrators seem more willing to act upon them. Princeton students want former president Woodrow Wilson's name removed from buildings because of his "racist legacy", external. Students at the University of Alabama are demanding changes to the names of four buildings, external over racist namesakes, and Yale students want a change to Calhoun College, named after a 19th Century advocate of slavery.

Georgetown changed the names of two buildings on its Washington DC campus this past fall: Mulledy Hall and McSherry Hall.

Thomas Mulledy was president of the university until 1838. He brokered the sale of 272 slaves owned by the Jesuit founders of the school. He split families, external, sold infants and the elderly. William McSherry helped arrange the sale. Nevertheless, two halls have born the men's names for almost 200 years.

"In terms of whether or not I would want to live in a place that had a slave owner's name - no, no, I wouldn't want to do that," says Shawn Allen, a junior at the college.

The buildings now go by "Freedom" and "Remembrance" halls.

However, even some supporters of the student movements worry that renaming buildings only papers over the parts of history we would prefer to forget.

"We don't want to do what's already been done in terms of hiding the history of an institution. I think it all needs to be out there," says Allen, who believes that old statues and plaques ought to at least be saved in universities' archives.

But Wilder argues that building names were never sacred, and that altering our language is inevitable.

"I'm more shocked it's taken us this long to think critically about the naming and titling process we use on campus, and how they may no longer fit our demographic," he says.

"I actually think what's happening right now is quite productive. It's forcing conversations that we should have been having for quite a long time."