The octopus that ruled London

- Published

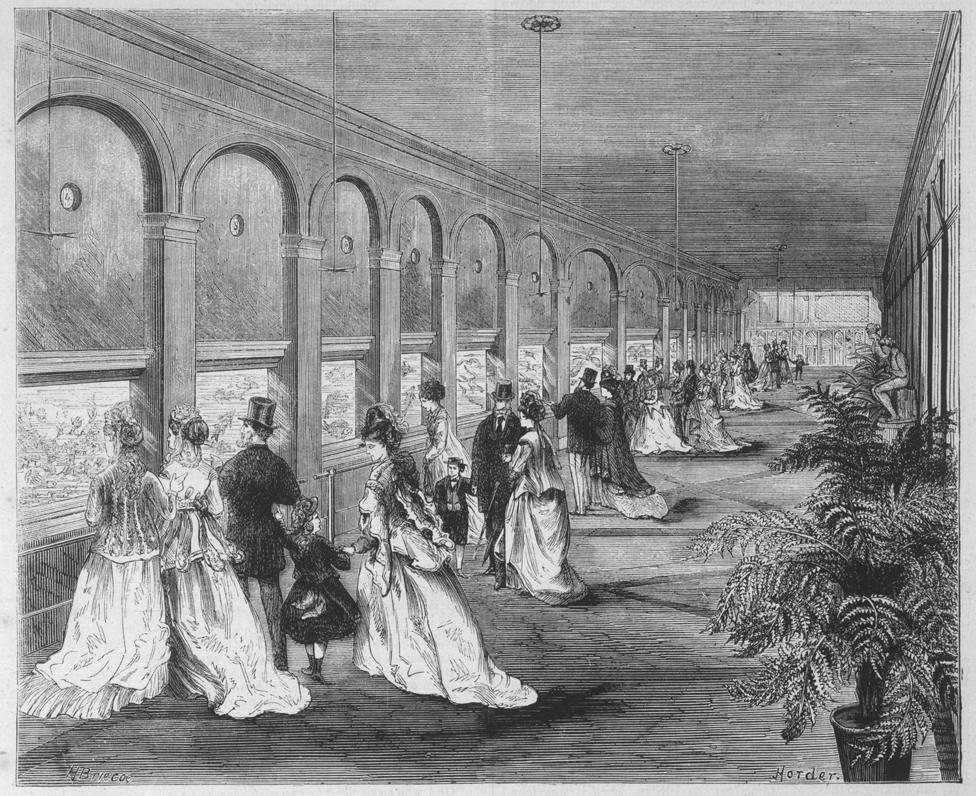

Sketch of the octopus from the Crystal Palace aquarium

Scientists have long pointed out the extraordinary scale of genetic differences between octopuses and most other animals. But the creatures also had the power to inspire terror in Victorian Britain.

Adults paid sixpence and the under-12s got in for half-price. Queues spilled into the grounds of Crystal Palace in autumn 1871 as the public waited for a glimpse of the biggest sensation in London.

It wasn't a freak show or a demonstration of the latest technology that attracted them, but a creature that had been around for millions of years, living in every ocean.

An advertisement in the Times informed potential visitors to Crystal Palace's new aquarium the chance to view "thousands of living creatures of the sea", but what everyone wanted to see was "the wonderful Octopus, or Devil Fish".

The eight-legged, boneless cephalopod mollusc (not a fish) had become a literary sensation, with the publication of Victor Hugo's novel Toilers of the Sea five years earlier. It featured a fight between a fisherman and a giant octopus. Hugo claimed the animal, well known previously to seafarers but little seen by anyone else, drank the blood of its "victims".

The Crystal Palace aquarium attracted crowds to see its octopus

"He draws you to him, and into himself," he wrote. "While bound down, glued to the ground, you feel yourself gradually emptied into this horrible pouch, which is the monster itself."

In 1867, a year after the publication of Toilers of the Sea, a captive octopus went on display at the aquarium in the French town of Boulogne. The Crystal Palace aquarium put one on display when it opened in 1871.

It "had to bear the uninterrupted gaze of on-lookers", according to JE Taylor, a noted Victorian writer on aquarium-related matters. "It sat for its portrait in the illustrated papers, and had all its points noted down by newspaper correspondents with the same faithful detail as if they were those of prize cattle at the Agricultural Show."

When another aquarium opened in Brighton in 1872, the presence of an octopus - the craze for which was becoming known as "cephalomania" - was de rigeur. The owners added to any Hugo-inspired sense of seaside terror by informing customers it had been "caught in a lobster-pot at Eastbourne".

The octopus

Octopuses divide into two types, the deep-sea finned octopuses and their finless, shallower water cousins

Most of the world's octopuses fall into the shallow water category

Many octopuses have poison glands, but few are toxic to humans - the bite of the blue-ringed octopuses is the exception

"It would have been a bit like a freak show for the Victorians," says Carey Duckhouse, curator of the Brighton Sea Life Centre, as the aquarium is known today. "They would have featured models of ships in the cases for the octopus to grab hold of. They would probably have loved that, as they enjoy playing."

One possible visitor to Crystal Palace aquarium was the writer HG Wells, who was just five years old when it opened and lived in Bromley, four miles away. Several octopus-like creatures appear in his stories.

In his 1894 essay The Extinction of Man, Wells pondered a "new and larger variety" that might "acquire a preferential taste for human nutriment". Could it, he asked, start "picking the sailors off a stranded ship" and eventually "batten on" visitors to the seaside?

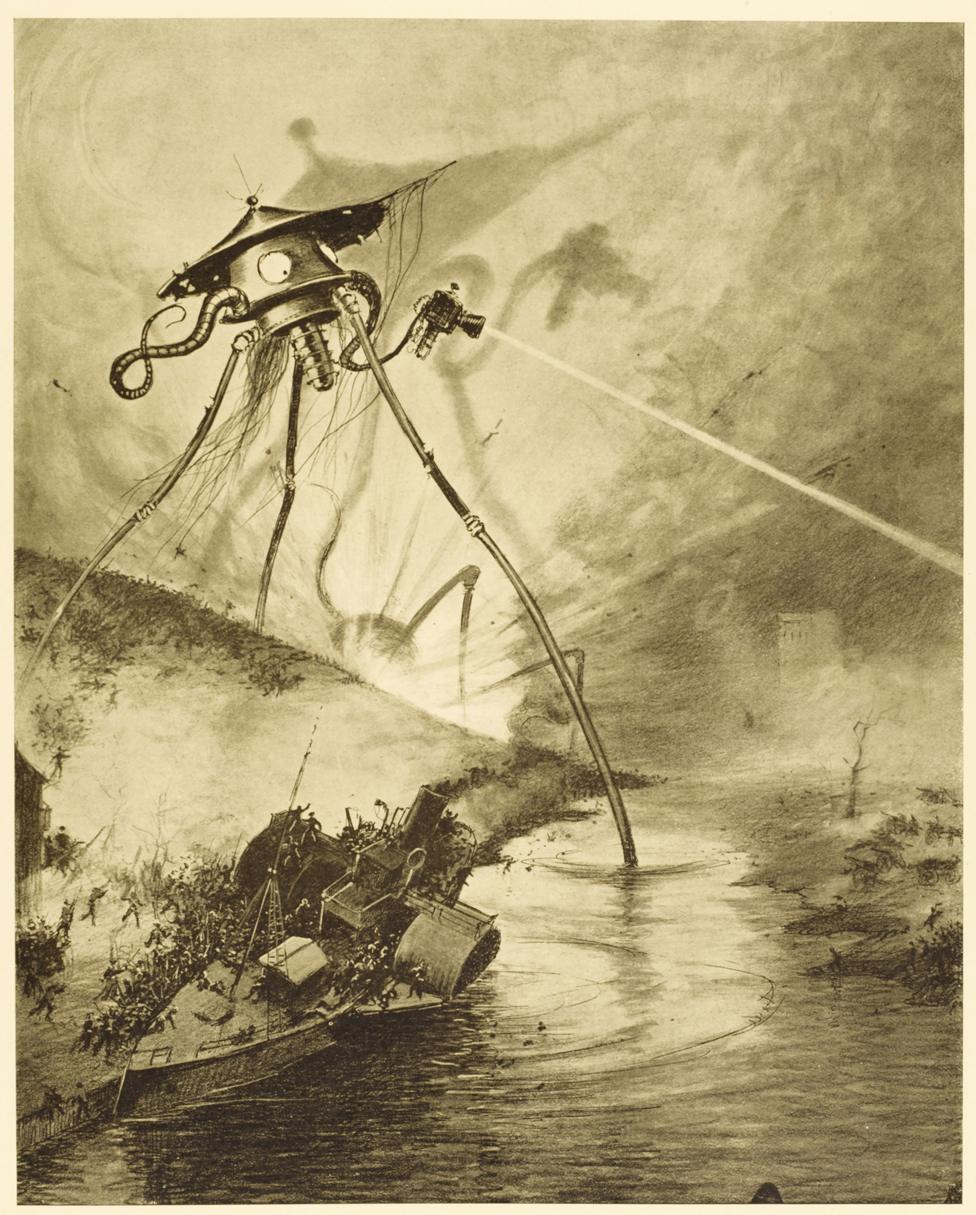

More famously, the invading Martians in Wells's War of the Worlds have tentacle-like arms. "To me it is quite credible that the Martians may be descended from beings not unlike ourselves," the narrator relates, "by a gradual development of brain and hands (the latter giving rise to the two bunches of delicate tentacles at last) at the expense of the rest of the body. Without the body the brain would, of course, become a mere selfish intelligence, without any of the emotional substratum of the human being."

An illustration from a 1906 edition of War of the Worlds: The Martian tripods have octopus-like tentacles

Octopuses, solitary creatures which live in dens, have hard, parrot-like beaks for killing, and tearing pieces of flesh. They pierce the shells of their prey, injecting poison that causes paralysis. They then release salivary enzymes, loosening the meat from the inner shell.

The HG Wells Society says there is no "compelling evidence" that Wells went to see the Crystal Palace octopus, but doesn't discount the idea. He wrote of seeing the dinosaur statues in the same park, external, the world's first attempt to create life-sized models of the ancient animals.

Cephalomania would have been hard for Wells to avoid growing up. A giant squid, related to the octopus, appeared in Jules Verne's 1869 novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, subsequently made into several films.

Tentacles have continued to be synonymous with creepiness and oddness. Cthulhu, a cosmic deity featured in the 1928 HP Lovecraft story Call of Cthulhu, has an octopus-like head. One of Spider-Man's enemies is Dr Octopus, a scientist who has designed four metallic tentacles to complement his arms and legs.

Research published last year showed that, so long ago was its genetic diversion from other creatures, that the octopus effectively had "the first sequenced genome from an alien, external".

Alfred Molina as Dr Octopus - one of Spider-Man's deadly enemies

The Crystal Palace octopus and its successors remained on display until the 1890s, when a monkey house replaced the aquarium. Attitudes appeared to soften during that period - the unfathomable moving to the outer realms of the edible.

"The octopus is highly valued as a bait for catching other fish," Andrew Tuer wrote to the Times in 1887, "but, while beloved of the Spanish and other seamen, it is not often eaten in this country. I had one curried and found it most excellent - something like tender tripe."

When Pink Floyd headlined The Garden Party concert at Crystal Palace in 1971, a century after the aquarium had opened, their performance included a large inflatable octopus. It floated on the lake in front of the stage, surrounded by dry ice - a scene Wells might have enjoyed.

In 2010, Paul, an octopus living at the Sea Life Centre in Oberhausen, Germany, was credited with correctly predicting eight results in a row. Was he using his "alien" powers to help humanity, or at least the part of it that liked a flutter, the press wondered. Statistical experts put his oracle-like qualities down to good luck.

Ironically, one of the ongoing attractions of the "alien" octopus is the ability to behave in what's seen as a "human-like" way, says Duckhouse. They can open jars and grab their handlers as they pass by open-topped tanks, looking for attention.

"They've got personality," says Duckhouse. "They would have seemed outrageous to the Victorians, but they are better understood today and people love them."

Follow Justin Parkinson on Twitter @justparkinson, external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.