Why has Britain stopped building bungalows?

- Published

The number of bungalows being built in the UK has collapsed, despite an ageing population. Why?

It's the building that's symbolised a quieter, gentler way of life for more than a century. Bungalows are sold as a dream for those approaching retirement, wanting to do without the hassle of having to climb stairs. They also provide easy access for wheelchair users and those unsteady on their feet.

With the UK's population ageing, demand for single-storey homes is likely to grow. But developers dealing with rocketing land prices are under pressure to build further upwards.

In 2014, just 1% of new builds in the UK were bungalows, according to the National House Building Council, external - down from 7% in 1996. The proportion of new homes which were flats or maisonettes more than doubled from 15% to 33%.

Plans for councils in England to sell off their higher-value properties to pay for more construction could result in 15,300 bungalows going into private hands, external by 2021, warns the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with many of them likely to be knocked down and replaced with multi-storey homes.

"Bungalows aren't the most valuable use of a building plot," says property expert Henry Pryor. "You get far more value from a two or three-storey building than you could get from a bungalow."

Last year, the government put the average price in England per hectare of land - with permission to build on - at £6m. Meanwhile, the UK's population is projected to increase to 74.3 million by 2039, which is likely to make land even more costly.

But much of this expansion will occur because people are living longer, meaning a greater demand for accessible housing. "It's certainly not as if bungalows are becoming less popular," says Pryor. "There are just fewer of them about because people aren't building them."

Ben Bartlett, a 74-year-old builder, has lived in a semi-detached bungalow in Truro, Cornwall, for 11 years. "It's great that there are no stairs," he says. "Everything's on one level, which makes life so much easier when you need to use the bathroom or go to bed. It's all set up ready.

"Some people can't get their head round the idea that you don't go upstairs to sleep, but lots of people can't do it. I feel really sorry for people, especially younger disabled people, who don't have access to what I've got."

The bungalow, perhaps in the countryside or by the sea, is often depicted as a retirement destination. People buy one, selling their larger family home - a phenomenon known as "downsizing". Often, older people are accused of not doing this early enough, inflating prices for families and first-time buyers.

Bungalow by the sea - the ideal retirement property?

But Pryor thinks there's another problem a stage further on. People, by now finding it difficult to live on their own, are unable to leave their bungalow because of a shortage of sheltered housing and care home places. So older retirees can't leave bungalows, younger retirees can't buy bungalows and younger people can't buy family houses.

"That's putting a brake on movement," says Pryor. "Generally there's very little sympathy for the older generation. They're reported as having had it too good for too long, but they do have problems."

The government's English Housing Survey for 2013-14 found just under one in 10 owner-occupied homes were bungalows - and 3.8% of private rental homes. Bungalows accounted for 10.9% of council homes and 11.2% of homes run by housing associations.

But a survey by YouGov for the Papworth Trust disability charity last year suggested 47% of over-55s wanted to live in a bungalow when they retired. The trust says it's possible to build two single-person bungalows on 69 sq m of land, external, the space normally taken up by a two-bedroom house.

One suggestion for overcoming prohibitively high land costs is building "stacked bungalows", external, two single-storey homes on top of each other, using a gentle slope rather than stairs to access the upper one. It's debatable whether these would still be bungalows or better described as easy-access flats.

An Indian tea plantation bungalow in the southern state of Kerala

Bungalow, from the Hindi word "bangla", meaning "belonging to Bengal", was used to described detached cottages built for early European settlers in India. They gained an association with a healthy outdoor lifestyle among the Raj, many of whom returned to the UK, extolling their charms.

The first development including houses sold as "bungalows" in the UK opened in Westgate, on the north coast of Kent, in 1869. The following year, a bigger project started at nearby Birchington. These were sold as getaways for wealthy Londoners.

The invention of more pre-fabricated materials such as plasterboard allowed building on cheap seaside land not suitable for homes needing more solid foundations. This allowed those on middle incomes to buy bungalows.

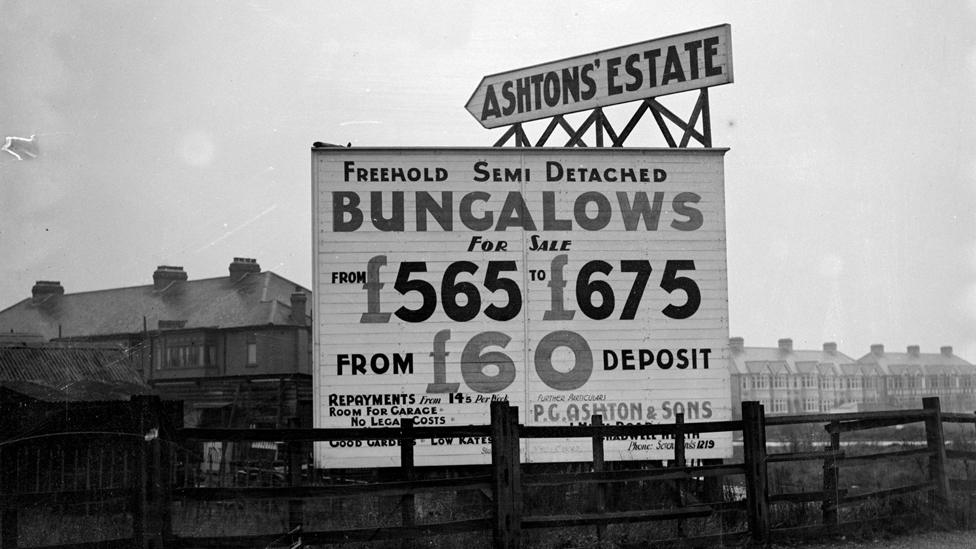

1937: A sign advertising freehold semi-detached bungalows for sale in Essex

The area between Shoreham and Lancing in West Sussex had a line of these buildings extending a mile and a half along the coast by the start of World War One, becoming known as Bungalow Town, external. Similar settlements started at Heacham in Norfolk, Selsey in West Sussex and Moreton in the Wirral. These places gained a sensuous, bohemian reputation, as the sexes could bathe together in freedom, with their homes right on the beach.

Bungalows caught on inland during the interwar years, with growing suburbs and garden cities fulfilling a demand for a less urban existence. However, architectural critics were scathing - nicknaming them "bungaloid growths", and blaming them for ruining the countryside. The "bungalow now stands for all that is vile and contemptible", wrote Thomas Sharp, in Town and Countryside, in 1932.

1957: A bungalow show house in Maidstone

More were built after World War Two, but the distaste continued. In 1982, Anthony Douglas King of Brunel University wrote that "in certain 'middle-class' circles in Britain - including the academic community - the mere mention of the term 'bungalow' is sufficient to provoke amusement, if not ridicule. Among a certain group or generation of architects and planners, the reaction is even stronger, occasionally leading to outright condemnation."

But economics, rather than snobbery, seems to be driving the downturn in building bungalows. Sandbanks in Dorset is far from typical of the UK property market. With several four and five-bedroom houses currently on sale for more than £6m, the small peninsula near Poole is rated one of the most expensive places to live on earth. But Sandbanks was once covered in bungalows, most having been replaced by luxury homes since the 1960s.

In 2011, interior designer Tim Baldwin demolished a bungalow bought there by his great-grandfather in the 1920s for £1,000, building a seven-bedroom house on the same plot that his family rents out for up to £4,500 a week. "I think the general redevelopment of Sandbanks is just the progression of things there," he says. "Whether you see it as improvement for the area is subjective. We still absolutely love visiting the place."

The bungalow in Sandbanks, Dorset, which Tim Baldwin demolished...

...and the house built in its place

Councils are able to deal with local needs, by setting "much clearer standards for accessible and wheelchair-adaptable new homes", says a department for Communities and Local Government spokesman. "We have also recently announced £400m to deliver specialist homes for elderly and disabled people, as well as putting in place new building regulations so more homes can be built to meet their needs."

Age UK says bungalows should be one of a "range of options" but the distribution of them varies by region and they must be close to amenities like shops and public transport.

But they'll get harder to build if anything because land prices are "killing the affordable housing market", says Rico Wojtulewicz, policy adviser to the National Federation of Builders. He argues that large firms dominating the construction industry are more likely to focus on traditional houses and flats.

"A bungalow's great for me," says Ben Bartlett. "I just hope, for the sake of future generations, that they start building some more."

Follow Justin Parkinson on Twitter @justparkinson, external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.