A Point of View: When does borrowing from other cultures become 'appropriation'?

- Published

A series of cases where Westerners (mainly white people) have been accused of stealing other people's cultures, leads Adam Gopnik to wonder what wrong has been committed.

You may have heard of the current kerfuffle here in America about the sin of what is being called "cultural appropriation". Some students at Bowdoin, a small liberal arts college in chilly Maine, were punished recently for wearing Mexican sombreros at a Mexican theme party. They had appropriated Mexican culture as a white person's prerogative.

Then, at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the practice of trying on a kimono for a selfie in front of a Monet painting of a French woman wearing a kimono was declared verboten for Boston, so to speak. It was a form of cultural appropriation of what belongs to Japan, while a production of Gilbert and Sullivan's "Mikado" was closed down for the same reason. It showed only a racist stereotype of Japan, as imperially imagined by Victorians. There have been more incidents, many at liberal arts colleges, involving Chinese food and the art form we wrongly call "belly dancing" and even the hugely popular practice of yoga. They belong to Others, and we cannot have them, or take them, for ourselves.

La Japonaise by Claude Monet

Now, I am not about to launch into a tirade against the "politically correct". I am old enough to recall that political correctness actually began as a term of self-mockery used by the hyper-sensitive, ruefully, against themselves, lightly guying their own good efforts at eliminating the casual sadism of daily interactions. "I guess I'm just being a little politically correct here, but…" someone almost always a woman) would say in the 1980s, and then point out an instance of unconscious sexism somewhere in the room. And in truth, "politically correct" is almost always these days synonymous with "sensitively courteous". We know this because when someone says "I am not going to be politically correct!", what he - and it is always a he - really means is, "I am not going to be sensitively courteous to anyone's feelings except my own and that of my gang!" We have a demonstration of this principle every night on our screens over here these days, and it is a nightmare.

Protesters at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts

Nonetheless, I would be lying if I did not say that the practice we call PC has its absurd aspects. It is funny because it puts more weight on the words we use than the actions we take, always a mistake. My son's dormitory at his liberal arts college has a live-in resident of deliberately indeterminate gender who wants to be referred to neither as "he" nor "she" - they are imprisoning patriarchal categories - nor as "it "(that would be an objectifying put-down) but as "they" and " them". This is at least convivial. When he - no, she - no, they - are there, it's always a party.

Find out more

Hear Adam Gopnik present A Point of View: The Love Of Honours on Radio 4, Friday 4 March at 20:50 GMT and repeated Sunday 6 March, 08:50 GMT - Catch up on BBC iPlayer Radio

There is something funny about this undue weight given to words, because we can't be endlessly sensitive and attentive and courteous in every interaction we have in life. People who try end up seeming insipid and exasperating rather than entirely admirable. My own wife, Martha, for instance, who does try to be so in every exchange, is, though much loved, also famous for the length of time it takes her to extricate herself from a social occasion, having first to be certain that she has been nice to everyone. This leads her, perversely, to avoid many social occasions for fear of wearing herself out from attentiveness - the price of such niceness can be very high. Prolonged punctiliousness is exhausting to all, particularly to husbands - er, mates - er, partners - er, co-habitating life colleagues.

But the idea that cultures - recipes or poses or even hats - belong to one group rather than another is something worse than a moment in a comedy of manners - or, rather, it misses the way that a larger comedy of manners has always shaped what we mean by culture. Cultural mixing - the hybridisation of hats, if you like - is the rule of civilisation, not some new intrusion within our own. Healthy civilisations have always been mongrelised, cosmopolitan, hybrid, corrupted and expropriated and mixed. Healthy societies seek out that kind of corruption because they know it is the secret of pleasure. They count their health in the number of imported spices on their shelves.

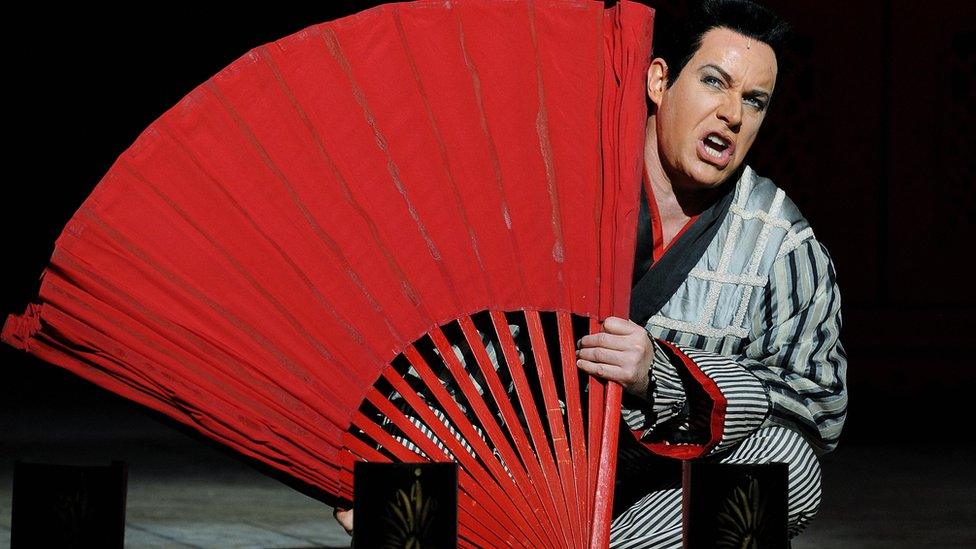

The Mikado

Comic opera set in Japan, written by WS Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan - its premiere was at the Savoy Theatre in 1885, where it ran for 672 performances

It remains one of the most popular musical theatre pieces in the world; a popular revival by the English National Opera, directed by Jonathan Miller, re-set the piece in 1920s England

The 1999 film Topsy Turvy, directed by Mike Leigh (pictured), tells the story of The Mikado's production

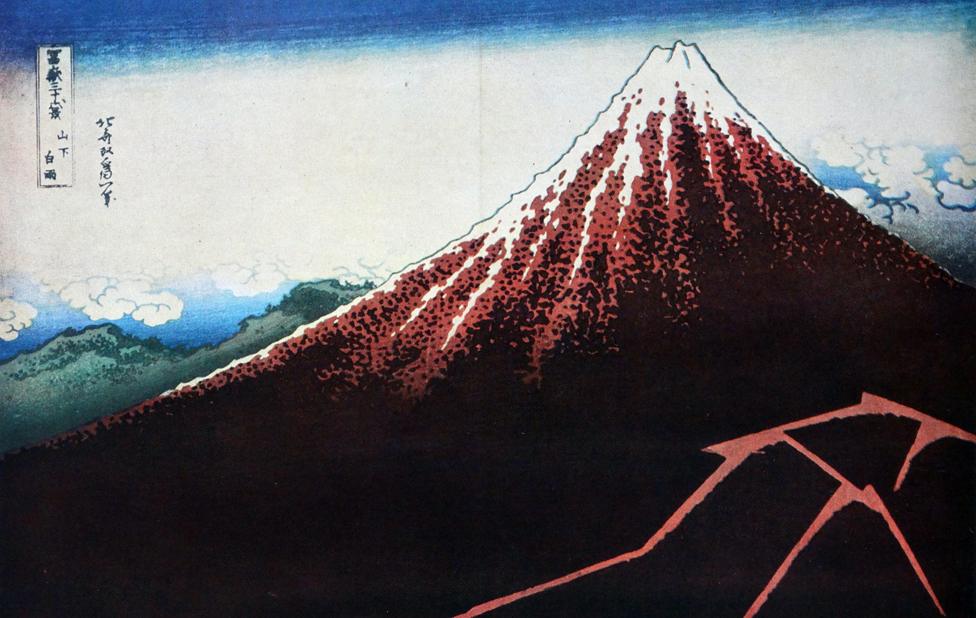

One of my favourite stories of how healthy cultural hybrids happen involves Japan and the West, though not, in this case, the Mikado. You know those beautiful 19th Century Japanese prints, by Hiroshige or Hokusai or their friends, poetically depicting everyday events, or favourite places, all in charming comic book colour, with Mount Fuji often delicately if secretively included in every view (like a kind of sublime Where's Wally). Those delicate black-edged figures and long almost cartoonish faces, those startling juxtapositions of foreground and distance, that informal and haiku-like lyricism - Japanese prints had, as everybody is taught in class, an enormous influence on French Impressionist art in the middle of the 19th Century. They were, exactly, an exotic appropriation.

"Shower Below The Summit" by the Japanese artist Hokusai

Well, it turns out that they weren't really exotic at all. They were the product of the Japanese infatuation with Western perspective drawing and graphics, which had only recently arrived in Japan on ships and boats as part of the Japanese opening to the West. The Japanese artists saw them, and saw expressive possibilities in them that the Western artists were too habituated to the system to notice. The Japanese appropriated Western perspective in ways that Westerners would never have imagined. Then the Japanese pictures got sent back to Europe, where they looked wonderfully exotic, and re-made the Western art they originally hailed from. It's exactly the same process that happened in our own lifetime when Howlin' Wolf and Big Bill Broonzy records sailed over to Liverpool and the suburbs of London and were heard by boys who barely understood their context but loved their attitude. Ten years later you got Mick Jagger and John Lennon. Innocent imitation is always the engine of cultural innovation.

Nor is it just that the borrowings can be beautiful. The things we borrow show us the things we are. Having passed through Chuck Berry, The Beatles and the Stones could better claim their own distinctive Englishness. In the same way, distinctly English food - all those real beers and farmhouse cheddars - has only gotten better because restaurants that served real Italian food helped showed how wonderful a coherent seasonal market-based cuisine could be. If we want to be ourselves, we have to travel - and nowadays, we do much of our travelling internally.

If all you know is your provincial culture, you don't know enough to know if your culture is provincial or not. When it ceases to be, you're not wise enough to recognise it. Appropriation is far more often empowering than oppressing. There's no cheaper way to get the drop on a bad guy than to borrow his hymns and habits and make them your own. That's what diaspora Jews have done throughout their history. It's how German bred with Hebrew to become Yiddish and Yiddish became the great language of Jewish folk tale and protest.

So cultures cannot be corrupted enough, civilizations cannot be appropriated too often. Nor is this only seen in heroic acts of original innovation. It's a nightly act of healthy practice. Last night, for instance, I made a Burmese curry, which combines Indian spices - cumin and turmeric - with the Chinese technique of stir-frying. The ingredients came from our local New York City Greenmarket - and I always mix butter in with the cooking oil, a habit picked up in Paris. The recipe also calls for yogurt, but my wife, of Icelandic extraction, prefers skyr, and it's all put together by me, while I amuse no one but myself by doing my very bad international accents. So it's actually a Jewish-Icelandic-Chinese-Indian-Burmese -French emigre-New York state stir-fry. All in one pot, and five minutes.

That's the norm of cooking. That's the norm of life. Blurring the boundaries of culture is what cooking does. When we do the same thing in ways that last longer than dinner, we call it art. Done often enough, it makes what we call civilisation.

So wear sombreros and kimonos and Mormon underwear beneath, if you so like. Eat Chinese food with Indian spices and French butter and celebrate the range of being human. We are mixed in nature, many in our very essence. We can't help it. To be human is to be hybrid. It is as close to a rule of life as you can ever hope to find.

A Point of View is broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 BST and repeated Sundays 08:50 BST

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.