The mothers who set up a radiation lab

- Published

Five years ago an earthquake off the coast of Japan triggered a tsunami and a series of meltdowns at the Fukushima nuclear plant. Kaori Suzuki's home is nearby - determined to stay, but worried about her children's health, she and some other mothers set up a laboratory to measure radiation.

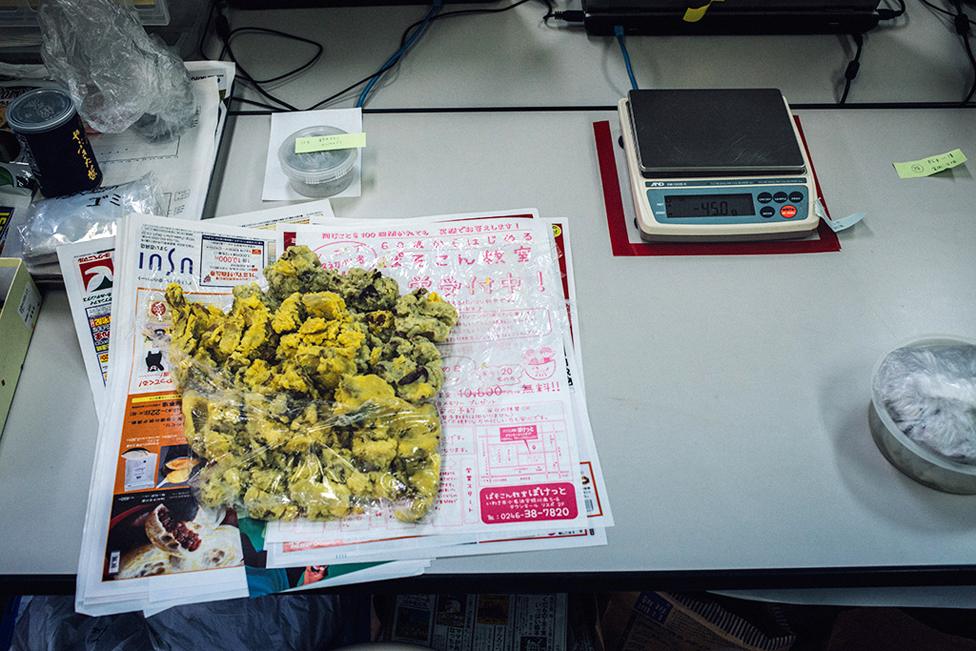

A woman in a white lab coat puts some yellow organic material on a slide, while grey liquid bubbles in vials behind her. Other women, one of them heavily pregnant, discuss some data on a computer screen. A courier delivers a small parcel which is opened and its contents catalogued.

But this is no ordinary laboratory. None of these women trained as scientists. One used to be a beautician, another was a hairdresser, yet another used to work in an office. Together they set up a non-profit organisation - Tarachine - 50km (30 miles) down the coast from the Fukushima nuclear plant, to measure radiation in the city of Iwaki.

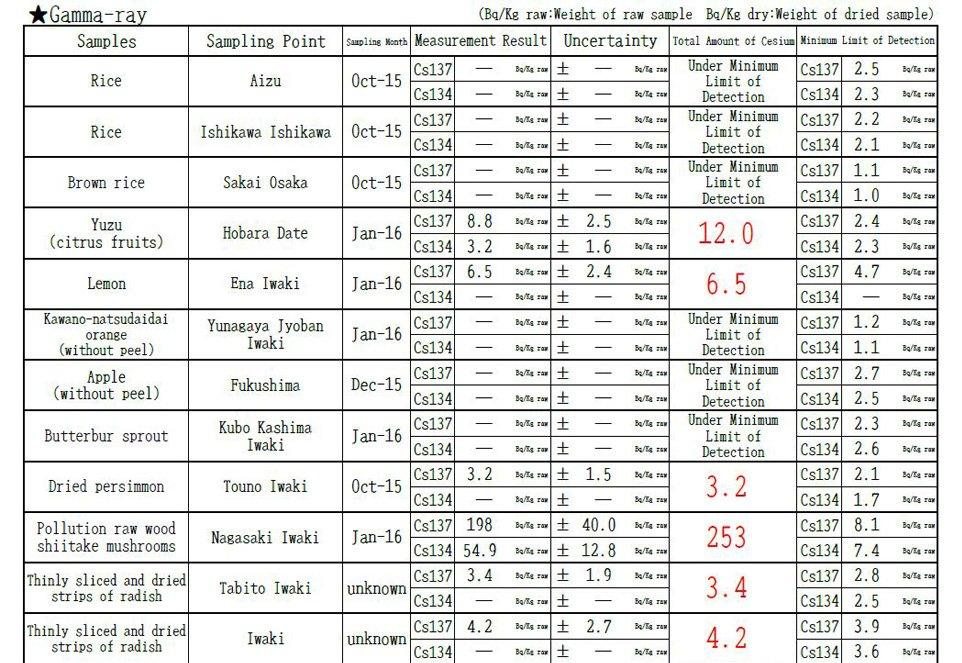

Kaori Suzuki, the lab's director, shows me a list of results. "This is the level of strontium 90 in Niboshi, dried small sardines, from the prefecture of Chiba," she says.

"What about this food?" I ask, pointing out a high number.

"Mushrooms have higher levels [of radiation]. The government has forbidden people from eating wild mushrooms, but many people don't care, they take them and eat," she says.

The lab mainly measures the radioactive isotopes caesium 134 and 137, and collects data on gamma radiation. Strontium 90 and tritium were only added to the list in April last year. "Since they emit only beta rays we weren't able to detect them until recently. Specific tools were necessary and we couldn't afford them," says Suzuki. Thanks to a generous donation, they now have the right equipment.

Tarachine publishes its findings online every month, external, and advises people to avoid foods with high readings as well as the places they were grown.

Find out more

Kaori Suzuki spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Get the Outlook podcast for more extraordinary personal stories

Five years ago, Suzuki knew nothing about radiation. She spent her time looking after her two children and teaching yoga. The earthquake on 11 March 2011 changed everything.

"I've never experienced so much shaking before and I was very scared. Right from the moment it started I had a feeling that something might have happened to the nuclear plant," she says. "The first thing I did was to fill up my car with petrol. I vividly remember that moment."

The authorities evacuated the area around the nuclear plant - everyone within a 20km (12-mile) radius was told to leave, and those who lived up to 30km (18 miles) away were instructed to stay indoors. Despite living outside the exclusion zone, Suzuki and her family fled and drove south. The roads were congested with cars and petrol stations ran dry.

"We didn't come back home until the middle of April and even then we wondered if it was safe to stay," says Suzuki. "But my husband has his own business with 70 employees, so we felt we couldn't leave."

Although radiation levels in Iwaki were officially quite low, the "invisible enemy" was all people could talk about. Conversations with friends changed abruptly from being about children, food and fashion, to one topic only: radiation. "You can't see, smell or feel it, so it is something people are afraid of," says Suzuki.

Above all, people didn't know what was safe to eat.

"It was a matter of life and death," she says.

Fukushima is farming country and many people grow their own vegetables. "People here love to eat home-grown food and there's a strong sense of community with people offering food to their friends and neighbours," says Suzuki. This caused a lot of anxiety. "A difficult situation would arise where grandparents would be growing food, but younger mothers would be worried about giving it to their children."

Suzuki formed the group "Iwaki Action Mama" together with other mothers in the area. At first they organised demonstrations against nuclear power, but then they decided on a new tactic - they would learn how to measure radiation themselves.

They saved and collected $600 (£420) to buy their first Geiger counter online, but when it arrived the instructions were written in English, which none of them understood. But they persevered and with the help of experts and university professors, organised training workshops. Soon they knew all about becquerels, a unit used to measure radiation, and sieverts, a measure of radiation dose. They would meet at restaurants and cafes to compare readings.

Becquerels and Sieverts

•A becquerel (Bq), named after French physicist Henri Becquerel, is a measure of radioactivity

•A quantity of radioactive material has an activity of 1Bq if one nucleus decays per second - and 1kBq if 1,000 nuclei decay per second

•A sievert (Sv) is a measure of radiation absorbed by a person, named after Swedish medical physicist Rolf Sievert

In November 2011 the women decided to get serious and set up a laboratory. They raised money and managed to buy their first instrument designed specifically to measure food contamination - it cost 3 million yen (£18,500, or $26,400).

They named the laboratory Tarachine, which means mothers - in particular, "beautiful mothers that protect their families" according to Suzuki.

"We felt as though we were on the front line of a battlefield," Suzuki says. "When you're at war you do what you have to do, and measuring was the thing we felt we had to do."

Today Tarachine has 12 employees, and more work than it can handle. People bring in food, earth, grass and leaves from their backyards for testing. The results are published for everyone to see. At first the lab was able to provide results after three or four days, but its service has become so popular it can hardly keep up. "We have so many requests for strontium 90 now that it can take three months," says Prof Hikaru Amano, the lab's technical manager.

Amano confesses he was surprised that a group of amateurs could learn to do this job so accurately, but says it is important work.

People began to mistrust the nuclear contamination data provided by the government and by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), which manages the nuclear plant, he says.

About 100 so-called "citizen laboratories" have since sprung up, but Tarachine is unusual because it monitors both gamma and beta rays - most can only measure gamma rays - and because it tests whatever people want, whether it's a home-grown carrot or the dust from their vacuum-cleaner.

The government does take regular readings from fixed points in Fukushima prefecture. It also check harvests and foods destined for the market, external - for example, all Fukushima-grown rice is required to undergo radiation checks before shipping.

But "if you want to know the level of strontium and tritium in your garden, the government won't do this measurement," says Suzuki. "If you decide to measure it yourself, you'll need 200,000-250,000 yen (£1,535, or $2,200) for the tests, and ordinary people can't afford to pay these costs. We have to keep doing this job so that people can have the measurements they want." Tarachine only charges a small fee - less than 3,000 yen (£18, or $27).

Mother of two Kaori Suzuki now spends much of her time at the laboratory

Tarachine also provides training and equipment to anyone who wants to do their own measurements. "Some of the mothers measure soil samples in their schools. It's fantastic, they really have become quite skilled at doing this," says Suzuki.

And the group keeps an eye on children's health. It runs a small clinic where doctors from all over Japan periodically come to provide free thyroid cancer check-ups for local children. Since screening began, 166 children in Fukushima prefecture have been diagnosed with - or are suspected of having - thyroid cancer. This is a far higher rate than in the rest of the country, although some experts say that's due to over-diagnosis, external.

And for parents who want to give their children a break from the local environment, Tarachine even organises summer trips to the south of the country.

Suzuki's own life has changed dramatically since 2011. "I was just a simple mother, enjoying her life. But ever since I started this, I've been spending most of my time here, from morning to night," she says. "I must admit, sometimes I think it would be really nice to have a break, but what we are doing is too important. We're providing a vital service.

"If you want to have peace of mind after an accident like the Fukushima one, then I believe you need to do what we're doing."

Kaori Suzuki spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published10 March 2016

- Published26 March 2011