The man who blew up Nelson

- Published

Fifty years ago this week an Irish republican blew up a statue of Nelson on top of a 41m-high pillar - not the one in London's Trafalgar Square but another in the very centre of Dublin. Now 83, the bomber says he has no regrets - but hates the spire that has replaced the admiral even more.

"He was the wrong man, in the wrong place at the wrong time," says Liam Sutcliffe, the man who made perhaps the most radical alteration ever to Dublin's skyline.

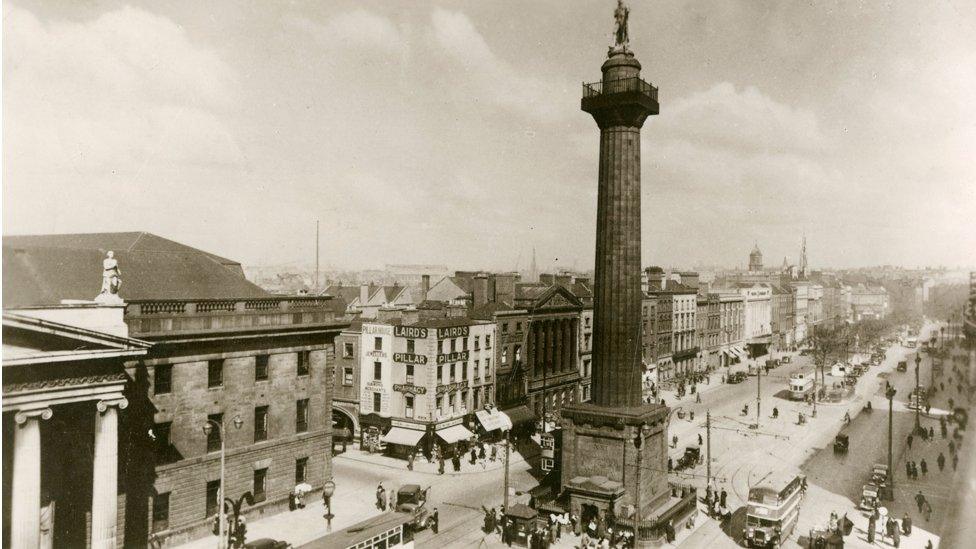

It was the city's most prominent monument by far. A place where young lovers met on their first date, or where folk would gather before a night on the town.

It had been there, towering over Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street) since 1809, thanks partly to the eagerness of Irish merchants - including the Guinness family - to pay tribute to an admiral who had made the high seas safe for trade. The £7,000 bill was paid for by public subscription.

The London statue, erected more than three decades later, was about 10m taller, but unlike the Dublin version it had no internal spiral staircase and no viewing platform that allowed the public to gaze at the city from Nelson's feet.

But if sightseers loved the Dublin pillar, nationalists hated it.

To them, France had been Ireland's "gallant ally", the Irish tricolour and republicanism inspired by the French. So a monument in Dublin to a British hero who'd beaten the French in battle was a double insult.

"Every generation tried to do the pillar - going back to the 19th Century, they were at it," says Sutcliffe.

The idea of demolishing the statue was hotly debated in the 1920s after Irish independence from the UK, but in the end nothing was done and an offer from a Liverpool demolition firm to do the job for £1,000 was turned down.

The 1916 uprising: Nelson's pillar stayed in place for another 50 years

A group of students tried and failed to burn Nelson down in 1955, and after that the debate picked up again as the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising approached in 1966.

The BBC's Alan Whicker was among those who acknowledged that the monument seemed out of place. Walking along O'Connell Street, he reeled off the Irish heroes whose statues lined the grand boulevard - Charles Stewart Parnell, William Smith O'Brien and Daniel O'Connell - before ending up in front of Nelson.

"Nelson?? How did he get up there?" he asked.

The same question was being asked by Liam Sutcliffe. In the 1950s he'd joined the British Army as an IRA spy to help plan raids on military barracks in Northern Ireland, for the purpose of seizing weapons. But by 1966 he had joined a militant splinter group led by the brothers Mick and Joe Christle - Joe being a flamboyant barrister who had taken part in the 1955 attack on the pillar as a young law student.

It was a chance conversation in a pub with a group of visitors from Belfast that sparked Sutcliffe's resolve to topple the statue.

"One girl said to me: 'Here we are in the capital city and there's still a big British Admiral in the middle of it.' What are you going to do about it?'" he recalls.

"She kept it up for a while, until I told her to wait and see."

Sutcliffe then approached Joe Christle, who revealed that a plan was already well-advanced, and invited him to be a part of it.

Nelson before the fall - photograph taken through mesh that was added in the 1950s

The idea was to place a bomb made from gelignite and ammonal on the viewing platform at the top of the pillar, with a timer set to go off in the early hours of the morning when the street would be empty.

In a decision Sutcliffe says he regrets today, he took his three-year-old son with him to avoid raising suspicions.

"If the Special Branch had their eye on the Pillar and seen me going in on my own with a bag under my arm they might have become suspicious - but with the young lad with me, they wouldn't pay any attention," he says.

"I realised after that this was a bad idea. If anything had happened that day, two of us would have gone."

While others kept watch, the two of them and an accomplice climbed up the spiral staircase one afternoon in late February or early March 1966, just before closing time. They planted the bomb and left. Sutcliffe then waited at home for it go off at 2am - but nothing happened.

Irish writers on Nelson's Pillar

"'They purchase four and twenty ripe plums from a girl at the foot of Nelson's pillar to take off the thirst of the brawn. They give two threepenny bits to the gentleman at the turnstile and begin to waddle slowly up the winding staircase, grunting, encouraging each other, afraid of the dark, panting, one asking the other have you the brawn, praising God and the Blessed Virgin, threatening to come down, peeping at the airslits. Glory be to God. They had no idea it was that high.'" (Ulysses, James Joyce)

"Grey brick upon brick, / Declamatory bronze / On sombre pedestals - / O'Connell, Grattan, Moore - ... And Nelson on his pillar/ Watching his world collapse." (Dublin, Louis MacNeice)

This was a problem. There was now an unexploded bomb in a public place in the centre of Dublin. So the next morning, as soon as the pillar opened again for tourists, Sutcliffe went back to collect it. He redesigned the timer, he says, and planted the bomb again a week later, on 7 March, this time without his son. Again it was just before closing time, and he was the last to leave.

"I shook hands with the caretaker and said, 'Thanks very much,'" he says.

"But I said to myself under my breath: 'You'd better start looking for a new job tomorrow.'"

At 1.30 am, a huge blast sent Nelson and tonnes of rubble on to the quiet street below, damaging a taxi - the only casualty of the night apart from Lord Nelson. The driver escaped injury.

This time Sutcliffe slept through the night and heard nothing.

On the way to work he met a woman at a bus-stop who asked if he'd heard the news about the attack on Nelson's Pillar. Then he saw the stories in the newspapers being read by other passengers on the bus.

"On the bus, a fella in front of me had the newspaper, holding it out, saying Nelson was gone. That was it - I knew. I felt great, nobody injured, no damage," he says.

The government officially denounced the attack, though it's said that President Eamon De Valera called the Irish Press newspaper, owned by his family, to suggest the light-hearted headline: "British Admiral Leaves Dublin By Air".

The government quickly took the decision to demolish what was left of the pillar. Sutcliffe thinks a ball and chain should have been used but the government opted for explosives - his hunch is that Taoiseach Sean Lemass and foreign minister Frank Aiken, both former IRA men and veterans of Ireland's war of independence, could not resist a final explosive farewell to Nelson.

"I pitied the army officer who had to do it. Their job was down low - I was up in the sky," says Sutcliffe.

"There was no need for a second explosion - but Lemass wanted a bit of a kick out of it, that he would outclass the first one."

The massive controlled explosion was followed by a deafening roar from celebrating crowds nearby.

This blast did far more damage than Sutcliffe's bomb, blowing out shop fronts along one of Ireland's busiest streets.

Balladeers had a field day. Tommy Makem released The Death of Nelson and The Dubliners wrote Nelson's Farewell, but most popular was Up Went Nelson by the Belfast group, Go Lucky Four, which topped the Irish charts for two months.

At the same time, Nelson's granite head began a peculiar journey.

Immediately after Sutcliffe's attack it was picked up off the street and taken to a municipal storage yard. But 10 days later it was stolen by students from the National College of Art and Design, looking for a way of paying off a Student Union debt.

Nelson turned out to be just what they needed. The head appeared on stage with The Dubliners, and in TV and magazine ads - including one for women's tights - and people would pay for it to be displayed at parties.

The police were on the students' trail, however.

At one event, plainclothes men rushed on stage to seize the stolen head - only to find the students had replaced it with a papier-mache version, leaving the original safely stored away.

"It took four of us to lift it on a piece of tarpaulin, just one at each corner," one of the students, Ken Dolan, told me when I interviewed him in 2005.

The students on Killiney beach with the stolen head: "It took four of us to lift it on a piece of tarpaulin," one recalls

"When it appeared with the Dubliners, they paid us. When it appeared on the Clancy Brothers album cover, they paid us. The film company doing the TV ads or the magazine ads, they all paid us. We just kept making money with it."

Ken Dolan and accomplices wearing balaclavas made by his mother. "She thought they were for a student fancy-dress party. She was shocked when she saw the photograph in the Evening Press and was worrying that her son had turned into a criminal!"

When the police attention became annoying, the head was taken to London, where antiques dealer Benny Gray paid for it to stand in his shop window - £250 a month, according to Dolan's 2005 interview.

"That was, in 1966, a lot of money, a lot of pints," he said.

Eventually the police rounded up a group of students unconnected with the theft, however, and the decision was taken to bring the head home. Benny Gray repatriated the granite remains ceremonially on a lorry which drove up O'Connell Street, joined by the Dubliners.

Today, Nelson's head sits in the corner of a library in Dublin, largely ignored.

Nelson's head in its current spot, the Dublin City Library and Archive

Looking the worse for wear, some of his scars date from the fighting which raged at the GPO building beside Nelson's Pillar during the 1916 Easter Rising. At least two pockmarks are caused by gunfire - the bullets most likely fired by British Army snipers, experts say, judging by the angle they came from.

Sutcliffe broke his silence to confess to the bombing on the Irish radio station RTE in 2000, but despite being arrested shortly afterwards he was released without charge. No-one was ever convicted of the plot.

He has not revealed the names of two others who were involved, in addition to the Christle brothers.

Liam Sutcliffe in 2016: Nelson "wasn't a hero for Ireland"

Not everyone in Dublin was pleased to see the pillar brought down.

In 1969, an Irish senator Owen Sheehy-Skeffington complained that "the man who destroyed the pillar made Dublin look more like Birmingham and less like an ancient city on the River Liffey — the pillar gave Dublin an internationally known appearance."

Ireland's foremost poet WB Yeats would probably also have been disappointed, had he lived to see it.

A generation earlier, in 1923, he had argued in the Senate against demolition saying that it represented "the feeling of Protestant Ireland for a man who helped break the power of Napoleon".

"The life and work of the people who built it are part of our tradition," he said. "I think we should accept the whole part of this nation and not pick and choose. However it is not a beautiful object."

In Nelson's place today stands the tallest structure in Dublin, the Spire, erected in 2003 and more than three times the height of the pillar.

The Millennium Spire on O'Connell Street

"I don't like the Spire," says Sutcliffe.

"It's absolutely unbelievable. I thought they should have done a better job.

"I much preferred Nelson, but unfortunately Nelson was in the wrong place. It would be like having a statue of Gerry Adams in Trafalgar Square. Nelson was a great hero - but he wasn't a hero for Ireland, he was a hero for England."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.