Whatever happened to the Great British nightclub?

- Published

The nightclub has fallen out of fashion so much that it is no longer viewed as statistically significant by the Office for National Statistics. What happened, asks Chris Stokel-Walker.

The Office for National Statistics' (ONS) basket of goods and services, updated annually and used to calculate inflation, reflects the nation's changing tastes.

In the 1970s it included Terylene slacks (or polyester trousers) and coal for domestic use. In recent years the ONS has removed satnav systems, frozen pizza and white emulsion.

This week it was the turn of nightclub entry fees.

"With the number of nightclubs charging entry declining," explains ONS statistician Phil Gooding, "we can no longer justify keeping these fees in the basket."

In 2005 there were 3,144 night clubs across the country, according to the Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers (ALMR). Last year, there were just 1,733.

The long list of press articles reporting the demise of nightclubs in cities across the country reads like a never-ending body count, each one a casualty of our changing society.

The London Astoria, which was demolished to make way for the Crossrail project

The lights went up at the end of the night for the last time at three clubs in Peterborough on New Year's Eve. Lowestoft's Winelodge shut in February 2015, while the owners of Electric Social sold up in March. Vibe in Clevedon - the town's only nightclub - closed in April. The Liquid & Envy clubs had their last dance in Luton in May; Burnley's Barcode club closed in June; Wonderland in Maidstone dimmed its lights in July.

Bristol's Syndicate club announced it would shut in August. In Blackwood, Vanilla Bar had its licence revoked in September. Rubix nightclub in Corby played its last track in October; Gatecrasher Birmingham had its licence revoked in November 2015, and Guernsey's Barbados nightclub was threatened with being replaced by a shop in December.

For clubbers faced with an ever-decreasing pool of venues to go to party and seeing only the empty shells and dulled disco balls of abandoned nightspots, there's just one question - why?

One of the most striking reasons is that the typical patrons of nightclubs - the young - have sworn off alcohol. One in five 16-to-24-year-olds do not drink, according to the ONS, and this has increased by nearly half between 2005 and 2013.

Those who do drink increasingly choose to do so away from nightclubs. Successive generations have lopped off the final step of the traditional "pre-drinks at home, drinks in a bar or pub, then club" night out. Many drinkers now stay at home until late in the evening, then visit a late-opening pub or bar, then go back home.

According to the British Beer and Pub Association, Britons drink more than a quarter less beer now than at the turn of the millennium. And where they drink has changed. "Off-trade" sales (those bought in supermarkets and off-licences and consumed at home) overtook "on-trade" sales (in pubs, bars and restaurants) in 2014. In 2000, on-trade sales were more than double off-trade ones.

Even on-trade business is splitting. "You get restaurants that become live music venues," says Dave Haslam, the author of Life After Dark: A History of British Nightclubs & Music Venues. "A lot of what used to happen in a nightclub is now happening in a number of [other] places."

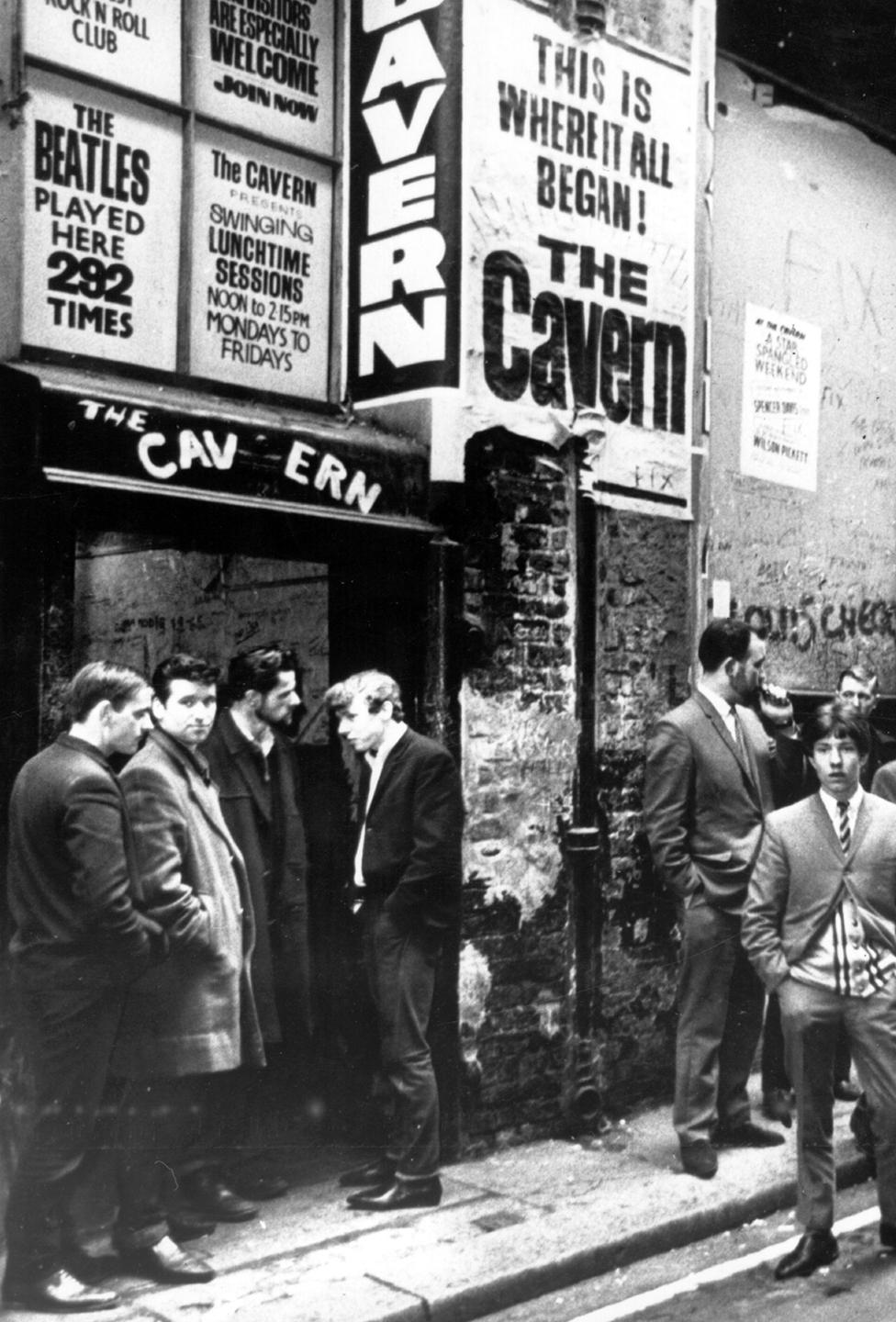

That's the general churn of nightlife, explains Haslam, who is also a DJ. Dancehalls dominated the 1940s and early 1950s, until clubs such as The Cavern appeared. "In all the research I've read I haven't seen a single report that says people go out less," he adds.

Ritwik Sarkar is a 21-year-old student at Newcastle University. He estimates that he only pays for club entry one in every five times he goes out in the city. "I'm a tad apprehensive about entry fees," he admits. "I don't usually like going to clubs. Usually we'll go to free places - they're as fun, and often have a better crowd." These include bars with small dance floors that stay open late.

Preferring free bars to paid nightclubs is a trend that has been particularly increasing in the past three to four years, explains Rachel Perryman of CGA Strategy, a leisure consultancy firm that focuses on nightlife.

"Places like Be At One and Revolution are low or no-cost to get in but are open until 2am or 3am," she says. "People can go there for food and then continue their big night out."

"In 2005 the only place you could drink late at night was a nightclub, therefore people were willing to pay to access that product," says Kate Nicholls, chief executive of the Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers. "A generation has grown up with music streaming services and is not used to buying a CD, never mind entry into a nightclub," she adds.

Late-opening bars are increasing in popularity as a place to spend the whole night, rather than simply the start of an evening. Revolution Bars Group, which runs the Revolution chain of cocktail bars, plans to open five to six new bars each year to meet demand.

"We've lost that high-tech discotheque," explains Haslam. "Most cities had three or four examples of it, where they'd serve warm beer, the boys would be able to have a fight and the girls could dance around their handbags.

"But," he adds," we're a more fragmented society now."

Nightclubs are being battered from all sides, with a variety of different options available for a night out that can include other options than simply drinking and dancing. "The challenge is not only from bars but other places, like street food venues," says CGA Strategy's Perryman.

According to surveys carried out by the consultancy, 39% of 18-35 year olds - the key club-going audience in Britain - go to street food or drink events. This can be alongside their regular trips to nightclubs, or increasingly in place of them.

Some club owners are upbeat. "Our own experience is not at all borne out in the ONS figures," explains Peter Marks, chief executive of the Deltic Group, the largest operator of nightclubs in Britain, including the Liquid and Chicago's brands. Five years ago admission fees accounted for 21% of the group's income from nightclubs. "Today, it's still 21%."

Nightclubs are fighting back, Marks says. The group doubled its investment in guest DJs last year to £2m. "Without DJs we're just a big pub," he admits.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.