A new threat in the mountains of Transylvania

- Published

The tradition of transhumance - the seasonal movement of sheep - is still practised in Romania. But shepherds say a law restricting the number of sheepdogs they are allowed to use could threaten their way of life.

"Do you want to see my house?" asks Ion at the door of the cowshed. I'm a bit nonplussed. We'd just been inside his house, on the sofa in the best room eating cake and poring over photo albums.

"No, no!" he says noticing my confusion. "I mean my real house!" He lifts a shaggy grey fleece off a wooden peg and throws it over his shoulders. The sleeveless sarica, as it's called, is made of four sheepskins sewn together. When I try it on, the cloak comes down to my ankles and is so heavy I can barely stand. But suddenly I'm immune to the knife sharp wind blowing off the mountains. "I slept in that even when it was snowing," says Ion. "Very cosy."

Ion and his wife Lenuta describe the long-distance walks they used to go on every year with their flocks of sheep between summer and winter pastures.

Lenuta shows me photos of donkeys carrying cooking pots, camping gear and canvas bags with small woolly heads peeking out. The newborn lambs get a free ride as their legs are too wobbly to keep up with the flock.

Romania is one of the few countries in Europe where this seasonal movement of livestock, or transhumance, is still practised but the tradition is dying out. New roads and the enclosure of privatised land after communism have made the walks covering hundreds of miles more difficult, even dangerous. Ion tells me he once needed several stitches after a landowner's security guard accused him of trespass and smashed him over the head. "These days you have to move your flock at night to stay out of trouble," he says.

"We just have these now," he adds as he pulls on the udders of a mud-splattered cow and milk squirts rhythmically into the pail. "We're too old to go on the road any more."

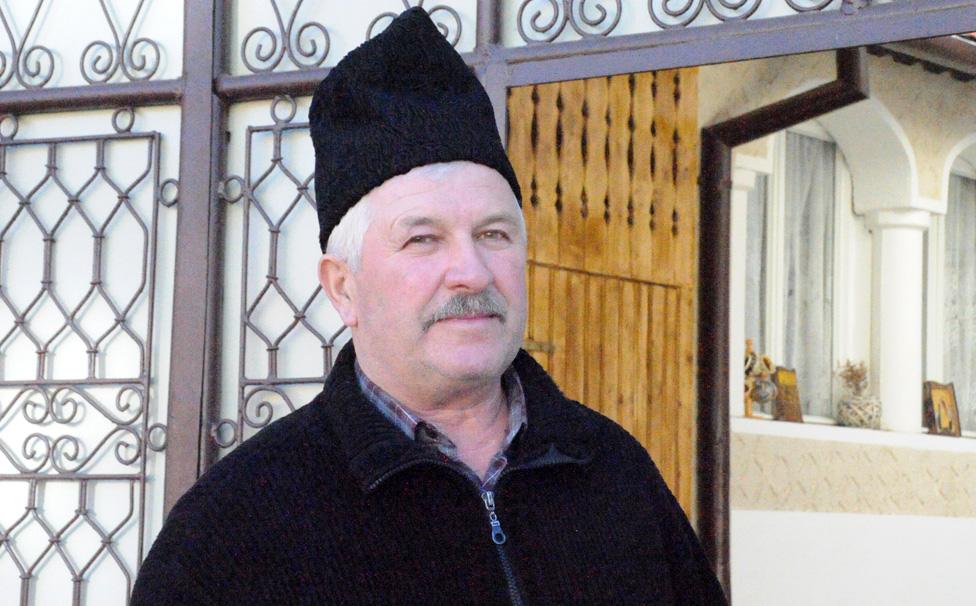

Fellow shepherd Dumitru Ciorgaru is no spring lamb either but he is reluctant to give up the life which he inherited from his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, who once took his sheep on expeditions as far as Crimean peninsula.

A tall, muscular man with a shock of grey hair, Dumitru has done well and over the years and quadrupled the size of his flock.

I am surprised to see so many shiny, top-of-the-range cars in this remote part of Transylvania. Ever since communist times, Poiana Sibiului and Jina have been famous for their wealthy sheep farmers. These isolated upland villages escaped collectivisation and some taxes under Ceausescu while the government guaranteed prices for the farmers' milk, meat and wool. So they flourished while most Romanians had to put up with empty shop shelves and power cuts.

One shepherd built himself a black marble swimming pool which he filled with petrol because it was strictly rationed at the time. People from the poorer plateau below were so impressed by the brick houses and mirrored windows that they used to talk of "going to America" when they paid a visit.

Find out more

Listen to Romania: The Shepherds' Revolt on Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday 24 March or catch up later online.

Dumitru also has a large house in the nearby village of Tilisca with neoclassical columns outside the front door. But he tells me he rarely sleeps well there.

"If I don't see my sheep for more than two days and leave them with my helpers I can't stand it - I start having dreams about them," he says. "Do you have a favourite?" I ask, feeling a bit foolish. "Every shepherd has a favourite sheep - one you pick and name and feed from your hand. It is just like a woman when you like her, your eyes shine and the feeling goes straight to your heart."

But he admits he was never lucky with his chosen ones - they would either die from overeating or be snatched by wolves. "Maybe faith teaches you not to love one sheep, you have to love your whole flock," he adds.

A shepherd walks with his flock of sheep near the village of Cudalbi in Romania

Dumitru may love his flock but he relies on his dogs for protection. The Carpathians are home to the highest number of brown bears in Europe and they often fancy snacking on sheep. Once a bear came at night and knocked him down but before it could rip him apart with its claws, the sheepdogs scared it off.

His eyes fill with tears at the memory of his narrow escape. Not surprisingly he was unimpressed by a law, passed last summer under pressure from the influential hunting lobby, enforcing a limit on numbers of sheepdogs.

I'm told about two-thirds of Romania's MPs are hunters and they claim the herding dogs attack deer, wild boar and other quarry. They want shepherds to have just one dog for grazing on the plain, two for hills and a maximum of three for mountain flocks. If shepherds flout the law, extra dogs can be shot.

"How can they tell me how many dogs I need?" Dumitru snaps. "They don't stay out all night in the cold. Those hunters just come and shoot, have fun and eat well. They don't know what hard work is."

Last December up to 4,000 angry shepherds in sheepskins, waving their staffs and blowing horns surrounded the parliament in Bucharest. As they began climbing over the walls into the courtyard, mounted riot police sprayed them with tear gas.

Dumitru boasts the shepherds could have stormed the building but restrained themselves. "Our MPs are like those mean and vicious bears," he says. "We have this saying: 'Bears go by and dogs bark' meaning politicians do whatever they want while unimportant people like us can only make a scandal."

The shepherds' noisy protest won them a temporary reprieve - the law has been suspended until April. But the row over Romania's countryside is far from over and just like the seasons, this threat to shepherds' livelihoods is bound to come around again.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.