The first Muslims in England

- Published

"True Faith and Mahomet" a needlework hanging at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire

Sixteenth-century Elizabethan England has always had a special place in the nation's understanding of itself. But few realise that it was also the first time that Muslims began openly living, working and practising their faith in England, writes Jerry Brotton.

From as far away as North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia, Muslims from various walks of life found themselves in London in the 16th Century working as diplomats, merchants, translators, musicians, servants and even prostitutes.

The reason for the Muslim presence in England stemmed from Queen Elizabeth's isolation from Catholic Europe. Her official excommunication by Pope Pius V in 1570 allowed her to act outside the papal edicts forbidding Christian trade with Muslims and create commercial and political alliances with various Islamic states, including the Moroccan Sa'adian dynasty, the Ottoman Empire and the Shi'a Persian Empire.

She sent her diplomats and merchants into the Muslim world to exploit this theological loophole, and in return Muslims began arriving in London, variously described as "Moors", "Indians", "Negroes" and "Turks".

Before Elizabeth's reign, England - like the rest of Christendom - understood a garbled version of Islam mainly through the bloody and polarised experiences of the Crusades.

The Medieval English view of Islam was viewed through the bloody experiences of the Crusades

No Christian even knew the words "Islam" or "Muslim", which only entered the English language in the 17th Century. Instead they spoke of "Saracens", a name considered in medieval times to have been taken from one of Abraham's offspring (with the servant Hagar) who was believed to have founded the original twelve Arab tribes.

Christians simply could not accept that Islam was a coherent religious belief. Instead they dismissed it as a pagan polytheism or a heretical deformation of Christianity. Much Muslim theology discouraged travel into Christian lands, or the "House of War", which was regarded as a perpetual adversary of the "House of Islam".

But with Elizabeth's accession this situation began to change. In 1562 Elizabeth's merchants reached the Persian Shah Tahmasp's court where they learned about the theological distinctions between Sunni and Shi'a beliefs, and returned to London to present the queen with a young Muslim Tatar slave girl they named Aura Soltana.

She became the queen's "dear and well beloved" servant who wore dresses made of Granada silk and introduced Elizabeth to the fashion of wearing Spanish leather shoes.

Painting showing the court of Shah Tahmasp receiving the Mughal emperor

Hundreds of others arrived from Islamic lands and although no known memoirs survive, glimpses of their Elizabethan lives can still be gleaned from London's parish registers. In 1586 Francis Drake returned to England from Colombia with a hundred Turks who had been captured by the Spanish in the Mediterranean and press-ganged into slavery in the Americas.

One of them, known only as Chinano, is the first known Muslim to convert to English Protestantism.

He was baptised at St Katharine's Church near the Tower of London, where he took the name William Hawkins, and insisted that "if there were not a God in England, there was none nowhere".

Perhaps he meant it and relished his new Anglican identity, or he knew what to say to his new English masters. Whatever the truth, like many of his fellow Turks he quickly disappeared into London's bustling life, taking with him his true religious beliefs.

How sincere Chinano's conversion was may never be known, but he was not alone, and others like him were clearly keen to make a living in diverse urban occupations.

They included weavers, tailors, brewers and metalsmiths. Other registers record Muslim women being baptised like Mary Fillis, a "blackamoor" daughter of a Moroccan basket-maker who after working in London as a seamstress for 13 years and "now taking some hold of faith in Jesus Christ was desirous to become a Christian".

Elizabethan London - busy enough for foreigners to disappear into

She was baptised in Whitechapel in 1597 where she presumably lived out the rest of her life. The faith of others was less certain, like the unnamed Moroccan who was buried the same year "without any company of people and without ceremony", because church authorities "did not know whether he was a Christian or not".

Nor were such conversions one-way. Hundreds of Elizabethan men and women travelled into Muslim lands in search of their fortune, and many converted - some forcibly, but others willingly - to Islam. They included the Norfolk merchant Samson Rowlie, who had been captured by Turkish pirates off Algiers in 1577, where he was imprisoned, castrated and converted to Islam.

He took the name Hassan Aga and rose to become Chief Eunuch and Treasurer of Algiers as well as one of the most trusted advisers to its Ottoman governor. He never returned to England or the Christian fold.

Elizabeth's alliances with the Ottoman, Persian and Moroccan empires also brought more elite Muslims to London. Records show that Turkish diplomats were sent over in the 1580s, though no trace of them survives.

More details remain of Moroccan embassies from later that decade. In 1589 the Moroccan ambassador Ahmed Bilqasim entered London in state, surrounded by Barbary Company merchants, proposing an Anglo-Moroccan military initiative against "the common enemy the King of Spain".

Although the anti-Spanish proposal came to nothing, the Moroccan ambassador sailed in an English fleet later that year that attacked Lisbon with the support of the Moroccan ruler, Mulay Ahmed al-Mansur.

Just over 10 years later another Moroccan ambassador called Muhammad al-Annuri arrived in London, with a large retinue of merchants, translators, holy men and servants who stayed for six months living in a house on the Strand where Londoners watched them practising their religious faith.

Muhammad al-Annuri, the Morrocan ambassador to England, 1600

One reported that they "killed all their own meat within their house, as sheep, lambs, poultry" and "turned their faces eastward when they kill any thing; they use beads, and pray to Saints".

Al-Annuri had his portrait painted, met Elizabeth and her advisers twice and even proposed a joint Protestant-Islamic invasion of Spain and naval attack on her American colonies. The plan only seems to have foundered because Elizabeth feared upsetting the Ottomans, who were at the time al-Mansur's adversaries.

The alliance came to an abrupt end with Elizabeth's death and her successor James I's decision to make peace with Catholic Spain, but the presence of Muslims like al-Annuri, Ahmed Bilqasim and more modest individuals like Chinano and Mary Fillis remain a significant but neglected aspect of Elizabethan history.

It shows that Muslims have been a part of Britain and its history much longer than many people have ever imagined.

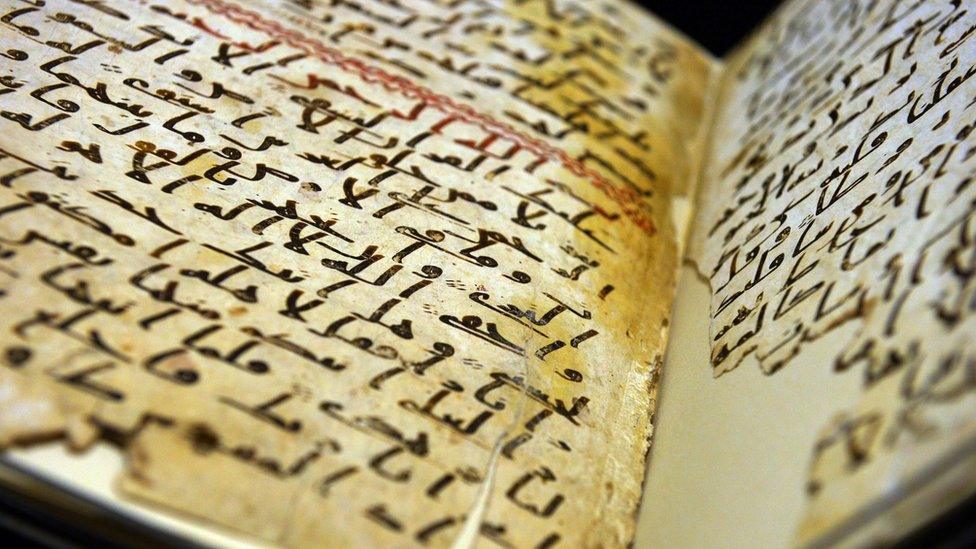

The Koran's long journey into British life

1095-1291 - The Crusades result in crusaders bringing some Middle Eastern customs and Arabic words back to England.

1588 - Christopher Marlowe's play Tamburlaine the Great contains a scene in which the Koran is burned.

1636 - Oxford University employs a chair of Arabic, who advocates a rational, historical approach to the study of Islam.

1734 - The first full translation of the Koran into English is made.

1869 - Lord Stanley becomes the first Muslim convert in the House of Lords.

1935 - Words from the Koran are broadcast on British radio for the first time, in BBC programme The Sphinx.

1997 - MP Muhammad Sarwar becomes the first person to swear his Oath of Allegiance on the Koran in the House of Commons.

Jerry Brotton is the author of This Orient Isle: Elizabethan England and the Islamic World

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox

Picture credits:

True Faith and Mahomet (silk), English School, (16th century) / Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, UK / Bridgeman Images

Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, Moorish Ambassador to Queen Elizabeth I, 160 (oil on panel), University of Birmingham Research and Cultural Collections