The cello and the nightingale

- Published

Beatrice Harrison during the first broadcast

It was a radio broadcast that spoke to the public, causing emotion and joy, a nightingale singing along with a cello. It was the first time people had been able to hear wildlife broadcast live on the UK radio and it would run until its poignant ending during World War Two.

On 19 May 1924, only two years after the dawn of BBC Radio, listeners heard for the first time an extraordinary duet live from a Surrey garden. The duet featured famous cellist Beatrice Harrison, who had recently performed the British debut of Delius's Cello Concerto specially written for her.

She played to a nightingale in the woods around her home in Oxted, Surrey, and the bird - seemingly attracted to the sound of her cello - responded with its own song.

Harrison first became aware of the birds one summer evening when she was practising her instrument in the garden. As she played, she heard a nightingale answer and then echo the notes of the cello.

When this was repeated night after night, Harrison knew that others should hear it and endeavoured to persuade the BBC to record the astonishing interaction.

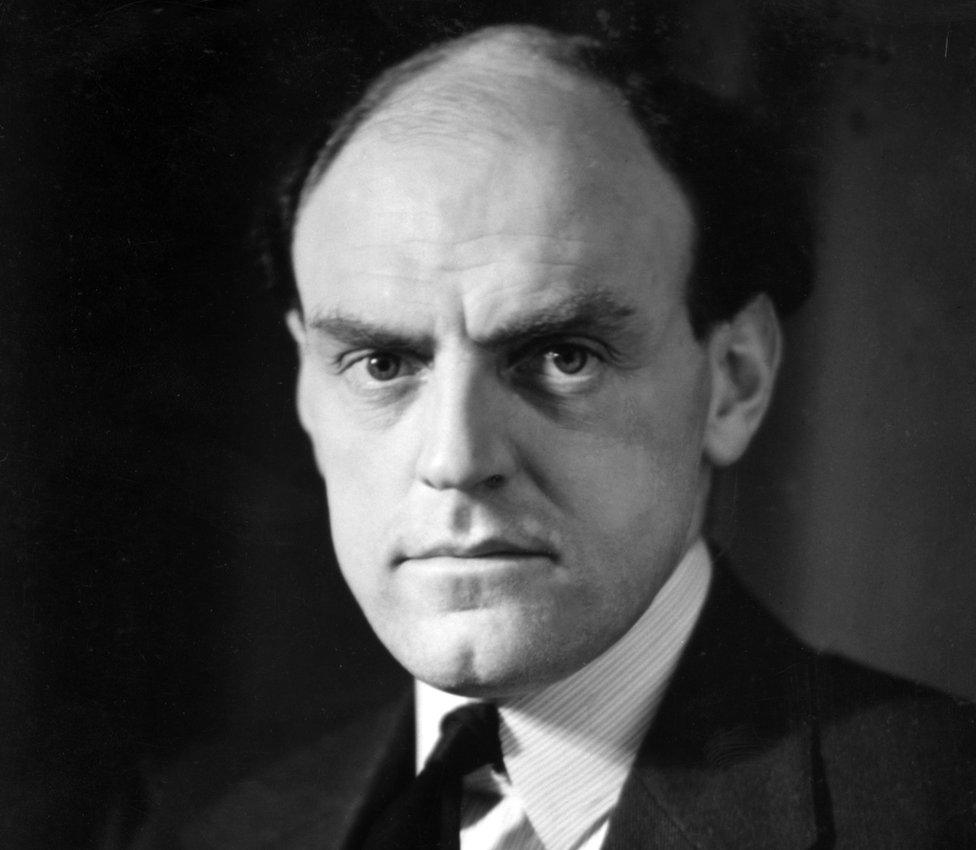

Lord Reith was less than enthusiastic about the nightingale

The BBC's founder and director general John Reith initially balked at the idea, complaining that the birds would be prima donnas - costly and unpredictable - and second-hand nature was not what people needed to hear. But Harrison succeeded and it went ahead anyway.

Will the nightingale sing?

Engineers prepare the microphones for the 1924 broadcast

Engineers carried out a successful test and the following night the live broadcast took place - one of the very first BBC outside broadcasts - with all the attendant complications of taking technology out of the station studio and on to location.

They interrupted the Savoy Orphean Saturday evening performance to go to Harrison playing Elgar, Dvorak, and the Londonderry Air (Danny Boy). No birds sang. It was a tense moment. Then finally, 15 minutes before the end of the broadcast, the nightingales started chirping.

Emotion and glamour

The public reaction was phenomenal. So much so that the experiment was repeated the next month and then every spring for the following 12 years.

Harrison and the nightingales became internationally renowned and she received 50,000 fan letters. Some even came from overseas, addressed simply to The Nightingale Lady.

First broadcast of Harrison with the nightingales

Writing in the Radio Times before the second broadcast, Lord Reith said the nightingale "has swept the country...with a wave of something closely akin to emotionalism, and a glamour of romance has flashed across the prosaic round of many a life".

He also said in his 1924 book Broadcast Over Britain: "Already we have broadcast a voice which few have opportunity of hearing for themselves. The song of the nightingale has been heard all over the country, on highland moors and in the tenements of great towns."

"[John] Milton has said that when the nightingale sang, silence was pleased. So in the song of the nightingale we have broadcast something of the silence which all of us in this busy world unconsciously crave and urgently need."

Bombers and nightingales

On May 19 1942, three years into World War Two, the BBC was back in the same garden planning to broadcast the nightingales (sans cello). But 197 bombers (Wellingtons and Lancasters) began flying overhead on their way to raids in Mannheim and the engineer realised a live broadcast of this event would break security.

Nightingales sing with RAF bombers overhead

The recording went ahead anyway since the lines to the BBC were open and a two-sided record was made, the first side with the departing planes, the second with their return (11 fewer). This recording is extremely poignant - the sound of the bombers throbbing behind the beauty of the bird song.

And why does the "glamour of romance" still touch me? I suppose it's partly for the same reason that Springwatch works its charm on audiences today. It's the belief that, even in this post-industrial age, we might still have some relationship with our "natural" neighbours. Nature touches us - and even more extraordinary, does not ignore us: a nightingale may answer a cello.

Nightingale and Cello - a poem

The nightingale and the cello - a poem

For more BBC archive material visit BBC Rewind on Facebook, external and Twitter, external.