Why can’t the date of Easter be fixed?

- Published

Easter is early this year for those in the Western churches on 27 March and late for those in the Eastern churches on 1 May. But why is there still no fixed day for Easter?

The English monk, the Venerable Bede, came up with a nice way of remembering when Easter falls - it's the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox.

"Astronomy is absolutely at the heart of setting the date for Easter. It depends on two astronomical things - the spring equinox and the full moon," says Dr Marek Kukula, public astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich.

Easter is a "moveable feast" and this is the earliest for almost a decade.

That's thanks to the complex system that developed from trying to calculate the date of Easter (and the Jewish Passover) from the heavens and trying to accommodate different calendars, on top of earlier attempts to harmonise how the date of Easter is worked out.

Indeed, The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, has said he hopes churches can agree to fix the date of Easter within five to 10 years, following discussions between the leaders of different Christian denominations.

The most common date for the Western churches' Easter is 19 April. The earliest Easter can be is 22 March, and the latest it can fall is 25 April.

Our calendar doesn't exactly match the astronomical cycles.

"So for literally thousands of years, people have been calculating, readjusting, and trying to make our artificial calendars a better match for the astronomy," says Kukula. "But because they don't exactly match, it means there's always a complexity in calculating things like the date of the equinox and the dates of the full moons."

While the Roman Catholic Church had its well-publicised falling-out with Galileo and the fruits of his astronomy in 1633, its need to calculate the dates for Easter and holy days meant that it had a long-standing interest in astronomy, and it established its first observatory in 1774.

The Vatican's present observatory at Castel Gandolfo, outside Rome

The convoluted system for working out when Easter will fall is the result of a mix of Hebrew, Roman and Egyptian calendars, culture and custom.

The Egyptians based their calendar on the Sun, which was adopted by Roman and then Christian culture, while Judaism bases its calendar partly on the moon, and Islam also uses the phases of the moon.

Easter's date fluctuates not least thanks to attempts to harmonise those solar and lunar calendars, with the issue further complicated by the fact that different strands of Christianity use different formulae for their calculations.

In 1582 the Gregorian calendar, which was adopted and promoted by Pope Gregory, was largely designed to make the date of Easter earlier, and easier to calculate. That is the calendar that we still use today.

Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar, still used throughout the Western world

According to the Bible, Jesus's death and resurrection from the dead, which Easter celebrates, occurred around the time of the Jewish feast of Passover.

That was celebrated on the first full moon following the vernal equinox. However, that soon led to Christians celebrating Easter on different dates. By the end of the 2nd Century, some churches celebrated Easter on the day of the Passover, while others marked it the following Sunday.

By 325, though, it seemed that the date of Easter was settled, thanks to the Council of Nicea.

The Council of Nicea settled many disputes within the Church, including the date of Easter

Easter was to be on the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the vernal or spring equinox.

Yet different traditions continued to calculate it in different ways.

For England, that's where the seaside town of Whitby came in. By 664, question marks over the date of Easter were causing concern in the royal household of King Oswiu in the kingdom of Northumbria. Rather embarrassingly, he and his wife, the queen, found themselves celebrating Easter on different Sundays. To settle the matter once and for all, the king called a synod at Whitby.

By 664, missionaries observing Irish traditions had come to Northumbria from the north, while from the south came missionaries sent from Rome by Pope Gregory the Great, led by St Augustine.

Whitby Abbey in Yorkshire - where the English church decided to follow the Roman observation of Easter

"And they evangelised different bits of the court here in Northumbria. So, King Oswiu was observing Irish traditions, whereas the queen was observing the Kentish, Roman, Continental traditions," explains historian Dr Michael Carter, of English Heritage.

"And one year it led to a terrible event - the king was observing Easter Sunday on one day, whereas the queen was still observing Lent, and the king couldn't have that."

So the synod thrashed out the question of when Easter should be observed. The Celtic or Irish case was put forward by Bishop Colman of Lindisfarne, while St Wilfrid, a native Northumbrian who had gone to the continent and been trained in Roman ways, put the Roman case.

"At a crucial point in the debate he mentioned St Peter - the keeper of the keys of the kingdom of heaven, which he was given by Christ himself. And King Oswiu, who was chairing the synod, was incredibly impressed by this," says Carter.

The decision went in favour of Wilfrid and the Roman way of calculating Easter.

"The Synod of Whitby made sure that the English Church observed the mainstream continental practice. It meant that the English Church was unified in its observation of the most important festival of the Christian calendar, the day of Christ's resurrection, and that England was tied to the continent. And it was something that persisted in England, a thread of continuity, until the English Reformation, when England was broken off from the religious and cultural mainstream of Europe."

But the Orthodox traditions within Christianity have stuck to the earlier Julian calendar, rather than accept Pope Gregory's reform to the calendar. That means that Orthodox churches continue to celebrate Easter (and Christmas) at a different time from Western or Roman traditions.

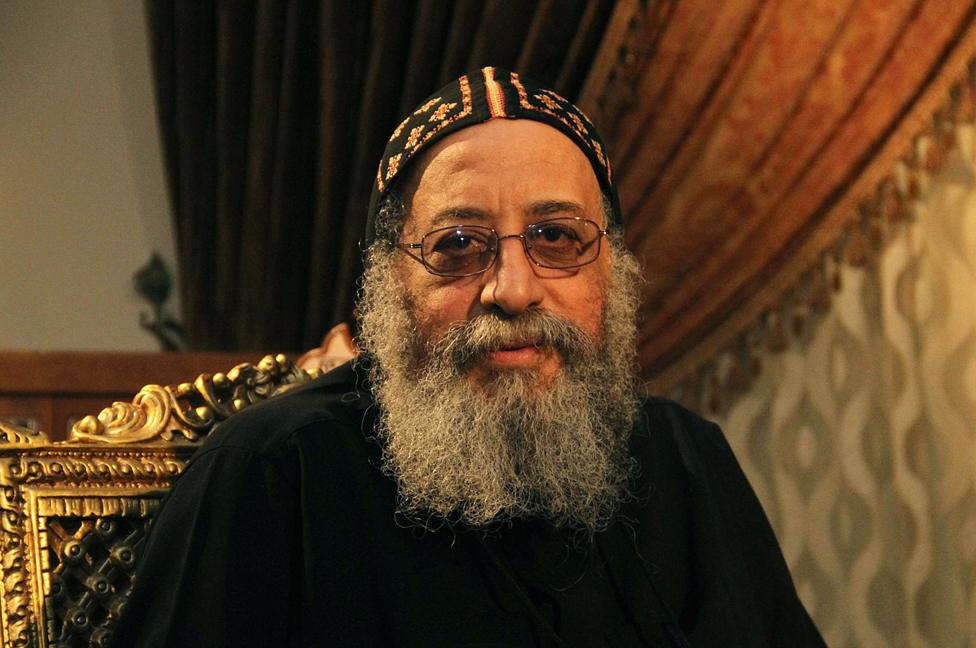

But might that change? Pope Tawadros II of Alexandria, leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church, is hoping that on this key issue, different branches of Christianity might be persuaded to compromise.

Pope Tawadros II, leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church

It was some time after a meeting with him that the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, came out with the surprising news in January that after many centuries of disagreement, there were once again hopes that the date of Easter could be fixed to a date on which all Christians could celebrate.

"During our visit to the Vatican in 2013, Pope Tawadros spoke about it again with Pope Francis in Rome," says Bishop Angaelos, general bishop in the UK of the Coptic Orthodox Church. "It seems as though there's an appetite among some of the leadership of the Christian church to at least pursue this possibility."

However, he admits that the path towards a shared, fixed date for Easter remains a long one.

"The difficulty is going to be that everyone will need to sacrifice something, because we all have our own ways of calculating Easter, and we've all calculated it this way for centuries," he says.

Bishop Angaelos explains why Easter dates cannot be set

As to a timescale, he admits it is "as long as the proverbial piece of string. We're speaking about a lot of people, a lot of different cultures, different churches and church leaders. And it's going to be a monumental task. But the thought is there."

It seemed for a little while, back in 1928, that the UK, at least, had found a solution. That was when the Easter Act was passed, which fixed the date as the first Sunday after the second Saturday in April.

However, the idea failed to catch on, and - although the original document still sits in the House of Commons archive - the British government has never brought it into force, because it agreed that would need to be done in consultation with Church leaders. That consultation might - at last - be on the horizon.

Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury during Easter service on 5 April, 2015

So what do astronomers make of the idea of fixing a date for Easter?

"Astronomy would be taken out of the equation in a sense," says Kukula.

"It would still be needed to regulate that calendar - you'd still need things like leap years and seconds - but Easter would stop being a moveable feast and that would make planning things like school holidays a lot simpler. However, whether that's a step that people want to take is a religious question."

And if history is anything to go by, it is a question that will continue to be debated for a very long time.

More from the Magazine

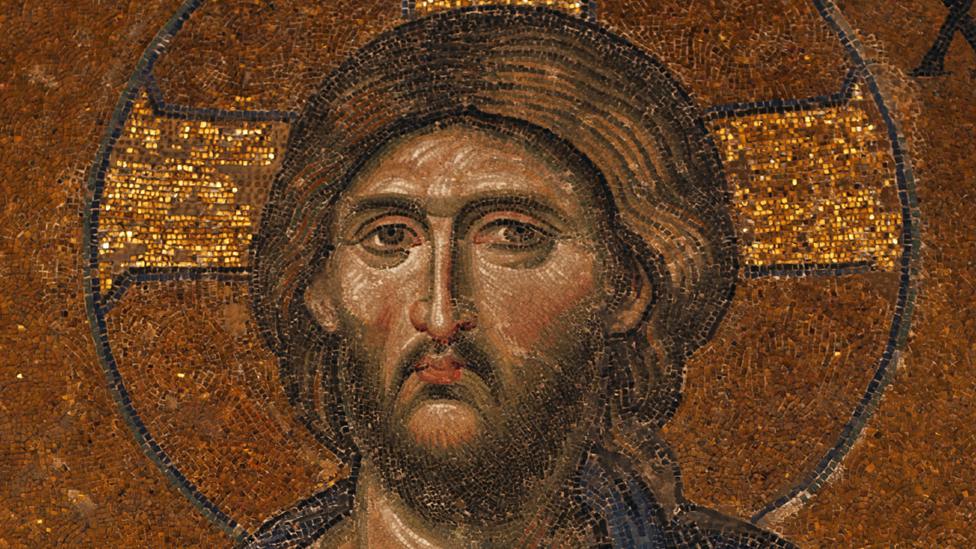

Everyone knows what Jesus looks like. He is the most painted figure in all of Western art, recognised everywhere as having long hair and a beard, a long robe with long sleeves (often white) and a mantle (often blue).

But how accurate is this image?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox