Jian Ghomeshi trial rattles sexual assault survivors

- Published

Jian Ghomeshi leaves court after the verdict on Thursday

Former radio personality Jian Ghomeshi has been found not guilty of all charges against him in a sexual assault trial that riveted the nation. Advocates say the verdict and the trial have had a chilling effect on sexual assault survivors across Canada. Journalist Ashifa Kassam explains why.

When the trial of former Canadian Broadcasting Corporation radio star Jian Ghomeshi began in downtown Toronto in early February, Jenni-Leigh O'Neill knew she had to be there.

She wasn't interested in stepping foot inside the courtroom where Ghomeshi - the one time host of the popular radio show Q, heard across Canada and in many parts of the US - was being tried on allegations of violently sexually assaulting several women.

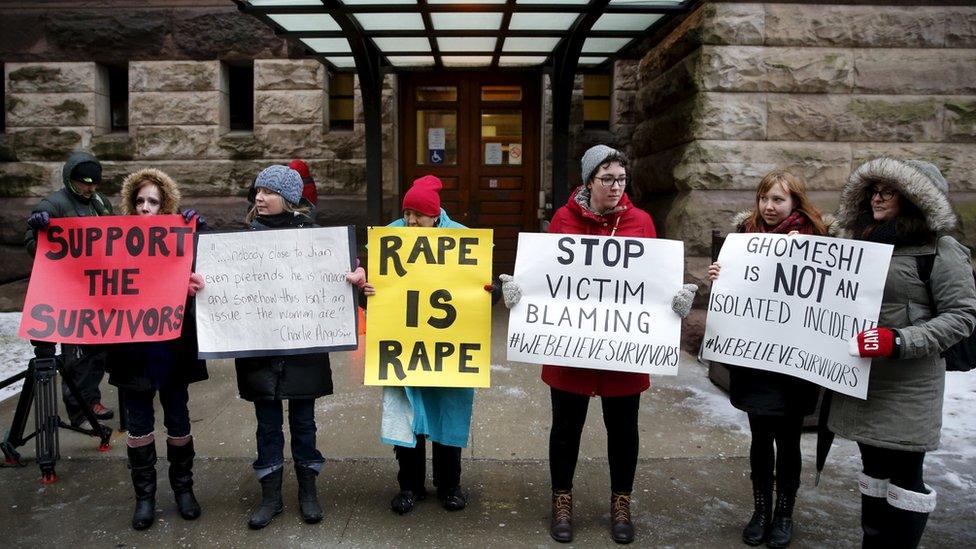

Instead the 27-year-old drove some 160 miles (257 km) from her home in Kingston to join a handful of other protestors outside the courthouse, spending hours each day in the biting cold to show their support for the three female complainants facing off against a man who once ranked among the country's most popular - and powerful - celebrities.

"I've been through a criminal court as a survivor of sexual assault," says O'Neill. "And I found it to be the most excruciating and painful experience I've ever been through, aside from having been sexually assaulted."

Ghomeshi pleaded not guilty to four counts of sexual assault and one count of overcoming resistance by choking. On Thursday morning, the judge in the case sided with him, acquitting the once-beloved radio personality on all charges.

"The twists and turns of the complainants' evidence in this trial illustrate the need to be vigilant in avoiding the...dangerous false assumption that sexual assault complainants are always truthful," Justice William B Horkins told the court, external.

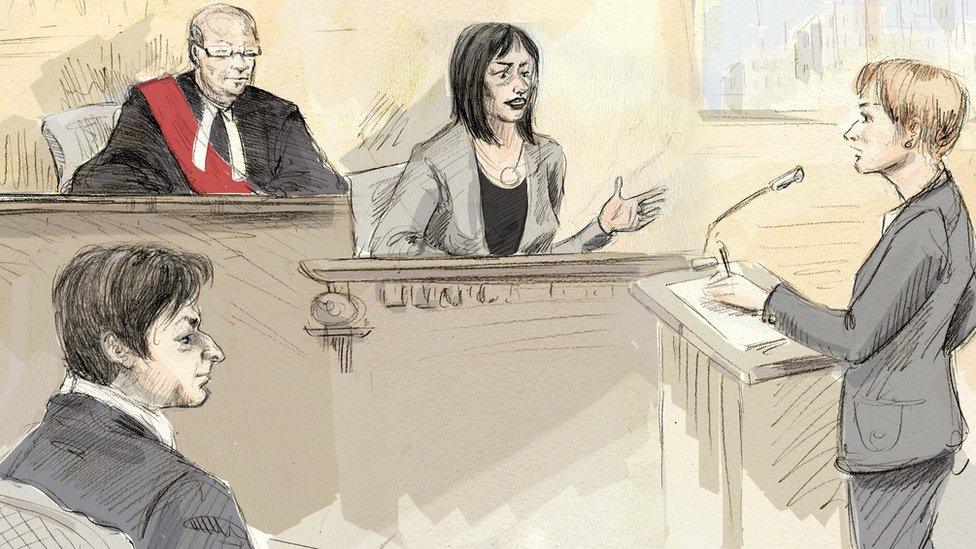

Court sketch of Lucy DeCoutere being questioned by prosecutors

The ruling affirmed some sexual assault advocates' worst fears - that it was the women who were truly on trial, not Ghomeshi. In the age of Twitter and live blogs, Canadians were given an unprecedented play-by-play account of the trial, and how the legal system deals with sexual assault allegations. For many, what they saw was profoundly disappointing, revealing a deeply flawed system in which the odds seem to be stacked against the complainants.

"We have a system that was built broken," says Farrah Khan, who runs a sexual violence support and education program at Toronto's Ryerson University. "How do we expect it to actually get justice?"

Ghomeshi's show Q was known for its A-list celebrity interviews and tackling tough topics such as rape culture and racism. He was fired in 2014 after the now-48-year-old showed higher-ups in the organisation a video that allegedly showed a woman being physically harmed.

Ghomeshi retaliated on Facebook, authoring a 1,590-word missive on his penchant for what he described as consensual "rough sex".

In the days and weeks that followed, more than twenty women and one man came forward with their own stories, telling various media outlets stories of being allegedly punched, slapped and choked by Ghomeshi without warning or consent, and prompting police to launch an investigation.

#BBCTrending: Ghomeshi accusations sparks social outpouring

As people came forward with stories of alleged assault, they sparked an extraordinary conversation across Canada and beyond.

Sexual assault survivors rallied together on social media, using the hashtag #BeenRapedNeverReported to share their own experiences and push back against cultural norms that had long kept them quiet.

But as the trial got underway, social media surrounding the case ceased to be a haven for survivors.

Protesters stand outside the courthouse in Toronto

"The live tweeting of the Ghomeshi trial is a clear reminder of why I, like so many other survivors, do not report sexual violence," Khan tweeted on the second day.

While it fed into the enormous demand for updates on the trial, many criticised what they saw as the public airing of intimate details about the women's lives.

Prompted by evidence presented by the defence, the three complainants made new revelations during the trial.

The first complainant admitted she had emailed Ghomeshi twice after he allegedly pulled her hair and punched her in the head, including a picture of herself in a bikini. She said she had been hoping to use the emails to bait him into talking to her about the alleged incidents.

The second complainant, identified as television actress Lucy DeCoutere after she waived her right to a publication ban, acknowledged an email in which she told Ghomeshi she wanted to have sex with him one day after he allegedly choked and slapped her.

DeCoutere said she didn't remember writing the email.

The third complainant said she had deliberately misled police when she didn't tell them she had engaged in sexual activity with Ghomeshi after he allegedly put his hands around her neck and squeezed as they were kissing in a park.

A shirtless protester was arrested by police after interrupting the prosecutor's statement outside the trial

She said she had been too embarrassed to tell police.

All of these revelations poured out to the public daily on social media.

"I'm worried that how this trial unfolded will create a bigger space for people to try to shove sexual violence back under the rug," says Lenore Lukasik-Foss, who heads the Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres.

The women's actions were not unusual, she says, considering they all had some sort of relationship with the accused and were detailing alleged incidents dating back to 2002 and 2003.

But the defence homed in on their behaviours, says Lukasik-Foss, hoping to shift attention away from the allegations and shed doubt on the women's testimonies.

"If you tear down the credibility of your witnesses, then perhaps they're lying, they're making this up."

The judge acknowledged this in his ruling when he said there was "reasonable doubt" about whether or not the assaults on the women happened the way they were described, and whether or not the complainants were actually displaying an "extreme dedication to bringing Mr Ghomeshi down".

"All of the extreme animosity expressed since going public with [DeCoutere's] complaint in 2014 stands in stark contrast to the flirtatious correspondence," Horkins said, external. "The harsh reality is that once a witness has been shown to be deceptive and manipulative in giving their evidence, that witness can no longer expect the court to consider them to be a trusted source of the truth."

Few dispute the legal necessity of a high level of proof. But often this leaves complainants feeling like they're the ones on trial, says Khan. "The trial is really a reminder of how we have not created a system to hold perpetrators to account."

It's a flaw that survivors and advocates often point to in order to explain why fewer than 10% of sexual assaults in Canada are ever reported to authorities.

With the shortcomings of the system again in the spotlight, reforms are being called for.

Suggestions range from legal assistance for complainants to the creation of specialised sexual violence courts, where everyone from judges to the prosecution would undergo training in trauma and intimate violence.

Specialised courts already exist in some parts of Canada, enabling the legal system to better interact with complex issues such as mental health and domestic violence, says lawyer Pamela Cross who works with Luke's Place, a centre that helps abused women in Ontario navigate the legal system.

While extending the idea to the issue of sexual assault wouldn't solve all of the problems laid bare during trials like that of Ghomeshi, it would at least be a start.

"It's like anything else. The more you know, the better," she says. "If everybody in that system knows a lot more about sexual assault, they're going to do their job better."

Ghomeshi will stand for a second trial, based on allegations of sexual assault from a fourth complainant, in June.