US election 2016: The 40-year hurt

- Published

The London-based American writer and broadcaster Michael Goldfarb is frequently asked on air why this year's US election has turned out to be so unusual, and whether insurgent Republican candidate Donald Trump can really win. He has to give a short answer. The long answer, he argues here, involves going back 40 years.

Bruce Springsteen is coming to London with the River tour. At £170 for the cheapest pair, I can't afford to see the Boss any more, even if my body could handle standing on Wembley Stadium's pitch for three-and-a-half-hours in an early June drizzle.

It's interesting that Springsteen is re-exploring The River album again. Whenever the anger that simmers in America erupts and reminds the rest of the world that the country is troubled, he seems to be the cultural figure whose work offers an explanation.

In late 1986, midway through Ronald Reagan's second term of office, with the twin scourges of Aids and crack racing through American cities and New Deal ideas of economic and social fairness consumed by the Bonfire of the Vanities taking place on Wall Street, Britain's Guardian newspaper ran an editorial that said, "for good or ill, [America] is becoming a much more foreign land".

I had just celebrated my first anniversary as an expat in London and wrote an essay trying to explain what America was like away from the places Guardian readers knew. I described the massive population dislocations that followed the long recession that had begun in the mid-70s. I referenced Springsteen. The piece ran under the headline "Torn in the USA".

Now America is going through even worse ructions. But there is nothing fundamentally new. What we are seeing is the continuation of a disintegration that began 40 years ago around the time Springsteen was writing the title song of the album.

The River, which came out in 1980, was very much about guys trying to kick back at father time and stave off the inevitable arrival of life's responsibilities - wife, kids, job, mortgage - and the equally probable onset of life's disappointments in wife, kids, job, mortgage, and in oneself.

The title track is a long, mournful story about that process and the narrator's desire to reconnect to the person he was when younger and full of hope.

"I come from down in the valley / Where mister, when you're young / They bring you up to do/like your daddy done…"

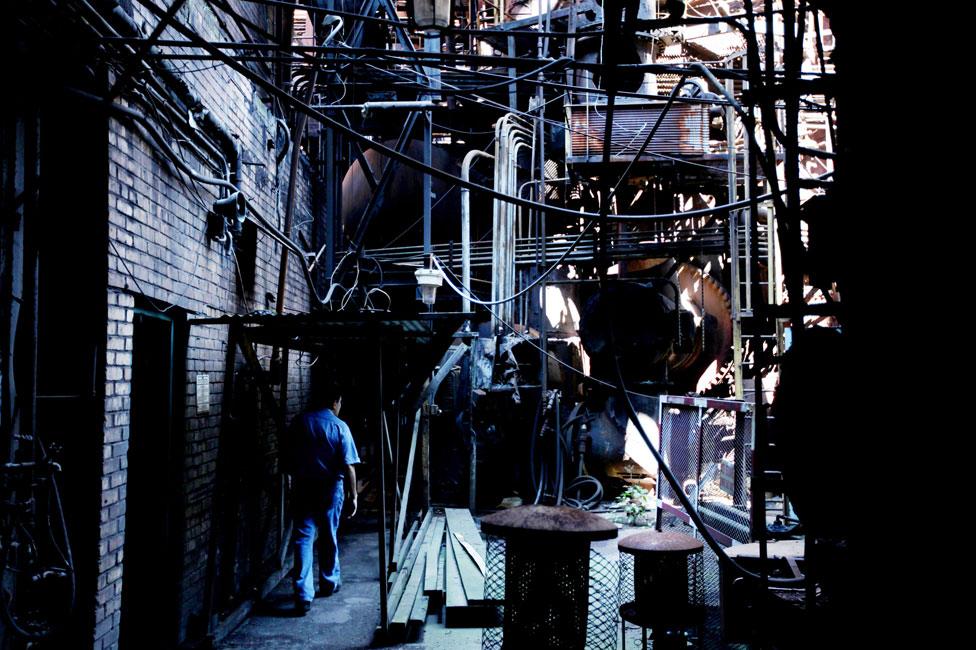

The key point is being brought up to be like your father. Work the same job, carry yourself in the same way, do the right thing. In the song, this tie that binds is seen as restricting the choices you can make in life. Your daddy worked in a steel mill, you will work in a steel mill, or on the line at River Rouge, or down a mine.

Today, what wouldn't many of us give for the economic and social stability that gave resonance to Springsteen's lyrics? A union job, 30 years of work, a pension. Sounds sweet.

The narrator of the song goes on to tell us, "I got a job working construction at the Johnstown company / but lately there ain't been much work on account of the economy."

Springsteen based the song on the struggle of his brother-in-law to stay employed during the bleak days after the Oil Shock of 1973: a half-decade of inflation and economic stagnation. At the time this stagflation was seen as a cyclical event; the economy would rebound soon. It would be boom time for all.

The economy did rebound, but then went into recession in 1982, and rebounded and went into recession at regular intervals, until the near-death experience of 2007/2008.

But very few people understood that an epochal change had taken place in the American economy. GDP would grow. Income wouldn't. Median salaried workers' wages stagnated. Those working low-wage jobs saw their incomes decline, external. As for job security, a perfect storm of automation, declining union power, and free-trade agreements put an end to that.

People who had been brought up to do as their parents had done wouldn't be able to do those things, they wouldn't even be able to live in the valley or towns surrounding the factories because there was very little work. A great migration south-east and south-west got underway, although "great diffusion" would be just as accurate a phrase.

How much does it hurt to leave the certainty in which you were raised, the community of family and church and friends who have known you forever? You go 500 or 1,000 miles south and live in an exurb built at the junction of an interstate in the middle of nowhere and have to work very hard to create that same sense of community.

You find a job, but unlike your daddy's job it isn't unionised, you work for less and you have very little security. When the economy slows, you know your job is at risk.

America grows richer for some but not for you. That hurts.

This is what I wrote about in 1986 for the Guardian.

In the autumn of 1992, when I had lived in the UK for seven years, the BBC World Service sent me back to the US to do a little reporting on the country in advance of the election. In a cafe in rural Maine, completely by chance, I ran into people whose lives were still upended two decades after the oil shock.

There were people in their forties who could not live as their parents had done be-cause the Great Inflation of the 1970s had permanently eroded the value of their salaries. There were people in their late sixties who found that their retirement savings had disappeared on day three of cancer treatment. They wanted someone to bear witness to their calamities.

More from the Magazine

Many people are not only angry, they are angrier than they were a year ago - particularly Republicans (61%) and white people (54%) but also 42% of Democrats, 43% of Latinos and 33% of African Americans.

Candidates have sensed the mood and are adopting the rhetoric. Donald Trump, who has arguably tapped into voters' frustration better than any other candidate, says he is "very, very angry" and will "gladly accept the mantle of anger" while rival Republican Ben Carson says he has encountered "many Americans who are discouraged and angry as they watch the American dream slipping away".

The following year, in 1993, I drove around the Midwest for the BBC to see if the election of Bill Clinton had changed things. It hadn't. The hurt was more on the surface if anything. In Cape Girardeau, Missouri, I met a high school principal, who was conservative and evangelical and hurting because a ballot initiative that would have raised property taxes a fraction of a cent to raise money to rebuild his dilapidated school and buy new text books had been voted down. He thought he was part of a community and had been shocked by the selfishness that vote demonstrated. He had recently retired.

There had been epic floods that year along the Mississippi. We walked down by the river and he pointed across to the Illinois shore where the flood waters had yet to recede. The principal told me, "Sometimes, I can't see where the river is going."

That was almost a quarter of a century ago. A lot of people still can't see which way the river is flowing: they want someone to do, whatever it takes to make the hurt go away.

In the last decade more people have joined the hurt club, and now, increasingly, it's the professional classes.

We know the pain of looking at our children and saying, what I had when I was your age I can't give you.

When I am asked to explain the Trump phenomenon on BBC radio and television, I know I don't have to teach this history. I have to stay focused on the day's events and explain a bit about the vagaries of the primary process. I have to bullet-point data: the polls, the employment figures, the wage stagnation. I have to throw the story forward because incredulous presenters end each interview by asking, "But can Trump win?"

And I think to myself there is no way to explain in a brief interview the power of the 40-year hurt in shaping American society. There is no number or data set that can measure its pain.

At the end of the River, Bruce writes, "Is a dream a lie if it don't come true/or is it something worse?"

Forty years of hurt have driven some people to answer Springsteen's question, that the American dream is something worse than a lie, and from that bleak answer they are looking for a political leader who echoes their anger.

So my answer to presenters' questions whether Trump can win, is now and was before the primaries started: "Yes."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.