Why is America pulling down the projects?

- Published

A Pruitt-Igoe tower comes down in 1972

For decades some of the poorest people in the US have lived in subsidised housing developments often known as "projects". Many of these projects, however, are now being torn down and studies suggest only one in three residents find a home in the mixed-income developments built to replace them.

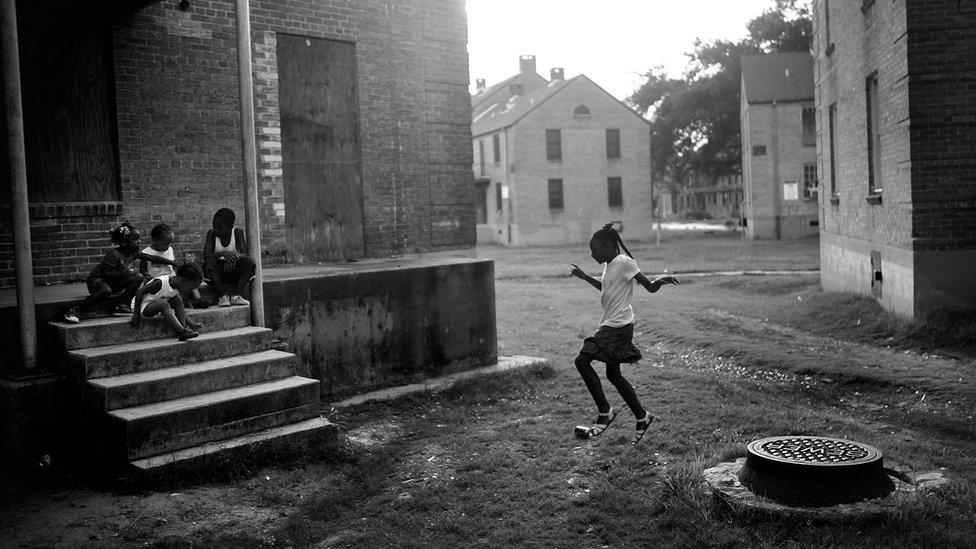

Windows are boarded up, chunks of plaster crumble from the walls and a collection of soft toys and flowers signifies the spot where a young man was recently killed.

"Animals get better care and attention to housing conditions than this," says Phyllissa Bilal. "People can go to a Third World country and say they're shocked at the horrible conditions. But then they drive past people here every day who live in the same."

Built in 1943, Barry Farm lies along one of the main commuting routes into the US capital. It is just over the Anacostia River from Washington Navy Yard, the US Navy's headquarters, and less than two miles (3km) from Capitol Hill.

But while few would choose to bring up a family here, when Bilal and her husband were granted a home in 2011 she says it "meant everything". Their previous home had burned down several years earlier and a house on the Farms, as the estate is known, offered them - and their five, soon six, children - "a chance to get back on our feet".

She has been proud to call the housing project home. "It's a community, it's almost like an extension of your family," she says. But now it is due for demolition.

Neglected and plagued by crime, it is one of thousands of public housing projects across the US deemed to have failed, and slated to be replaced by mixed-income developments, of homes and shops.

But during the process of destruction and reconstruction, Bilal does not know where her family will go.

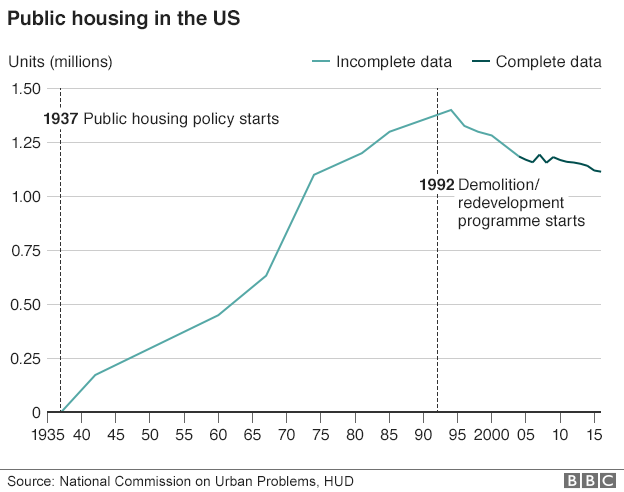

The construction of public housing became national policy in 1937 as part of President Franklin D Roosevelt's New Deal - a series of social reforms introduced in response to the Great Depression. Ed Goetz, author of New Deal Ruins: Race, Economic Justice, and Public Housing Policy, says many public housing projects built during this time were successful, well-built and well-managed.

Some remain popular today. Plans to redevelop the country's first federally funded housing project for African Americans - Rosewood Court in Austin, Texas - have prompted a campaign to protect it by securing recognition of its historical importance.

Public housing in the US

About 1.1 million homes in public housing in the US, compared to more than 2.5 million in the UK (not including those owned by housing associations)

More than a third of those living in public housing in the US are under 18

The average annual household income is $14,455 (£10,234)

Most public housing tenants spend 30% of their income on rent

At least 1.6 million families are said to be on waiting lists - disabled people, the elderly and families with children, often get preference

Sources: HUD, ONS, Scottish government, NISRA, PHADA

Although black and white people lived in separate buildings, the housing projects of the 1930s provided homes to working-class residents of all races.

But this changed after World War Two when new low-interest mortgages helped white working-class people buy homes in the suburbs. A 1949 law also made public housing available only to people on the lowest incomes. So in time the projects began to house only the poorest minority communities.

The US government had aimed to build one million homes in public housing projects by 1955, but by 1967 only 633,000 were in use. In an attempt to cut costs, many housing authorities also began skimping on materials and construction. From that point forward, the buildings tended to be neither well-made nor well maintained, says Goetz.

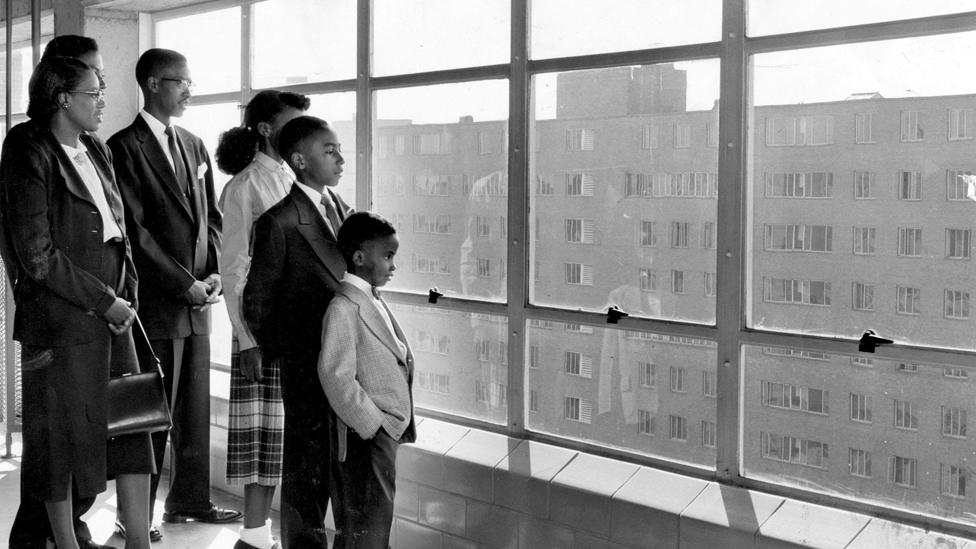

By the early 1950s high-rise projects were being built that would soon become symbols of the problem with public housing. One was Pruitt-Igoe in St Louis, advertised as a paradise of "bright new buildings with spacious grounds" when it opened in 1954, but already by the mid-1970s crime-ridden, half-deserted and barely fit for habitation.

Projects such as Pruitt-Igoe collapsed "badly and quickly", says Ed Goetz, leading popular consensus to view the whole public housing programme as a "spectacular failure".

Families who moved into Pruitt-Igoe in 1954 were promised smart homes with modern amenities

Water pipes burst in 1970, covering homes in ice

Crime is one yardstick by which that failure has been measured. One study by the US Department of Justice found the number of violent offences committed every year between 1986 and 1989 in housing projects in Washington DC was almost double that in nearby neighbourhoods - 41 crimes per 1,000 residents, compared to 23. Another study, carried out in 1994, found that nearly 30% of residents living in one public housing project in Chicago said a bullet had been shot into their home in the previous 12 months.

Public housing officials came to see the problems associated with the projects as the "concentrated effects of poverty", says Goetz - problems that could be solved by creating mixed-income communities where public housing residents lived among wealthier neighbours.

"At least that was the prevailing theory," says Goetz. "Other things were involved, including the revival of the real estate markets in central city areas."

In 1992, housing officials began receiving government grants to tear down and replace the worst public housing complexes. Housing agencies had demolished or otherwise got rid of 285,000 homes by 2012 and replaced only about a sixth, according to a report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington-based research institute.

Another 42,000 units have been lost since then, government figures suggest, leaving the volume of public housing at a level last seen in the 1970s.

David Layfield, an affordable housing expert, says it is important to remember that many of the projects being demolished have been largely abandoned - with vacancy rates of up to 30% in some places - because they were so uninhabitable.

"The reality is that public housing is being improved drastically - being made more durable and more energy efficient," he says. "And in many cases the developers have diversified the income levels."

Most public housing is low-rise - construction of high-rise projects was banned in 1968

Amid stories of trees growing through the living rooms of crumbling properties and residents being attacked outside their homes, many residents of Barry Farm welcome a new start. However, some are determined to fight the development.

"The process of transformation looks good on paper but across the country it has not worked and it is not going to work here," says Phyllissa Bilal.

One of the main concerns is that current residents will not be able to return once the site is redeveloped.

Many of the homes in Barry Farm are boarded up, with padlocks on the doors

"This isn't the perfect place but at the same time this is still my home," says Paulette Matthews, who has lived at Barry Farm since 1995. "When you take people out of these places where are they going to end up?"

Developers are required by law to help residents relocate during the demolition and construction process, and on paper they have a right to return to the redeveloped property - but on average, it has been estimated, only one in three do.

People often "fall out of the system", says Goetz. "Much too little is done to make sure original residents really benefit."

The housing authority in Washington DC says that all the public housing homes on Barry Farm will be replaced on a one-to-one basis and it has offered to help current residents move to alternative public housing projects, apply for government subsidies to pay for private rentals or try to buy their own home.

History of Barry Farm

Anacostia area originally inhabited by the Nacotchtank tribe of native Americans

European settlers arrived in mid-1600s

Site of a significant community of formerly enslaved and born-free African-Americans after the Civil War

Public housing built in 1943 to house workers flocking to the city for jobs during World War Two

But Paulette Matthews says local turf wars and the existence of gangs make moving between public housing projects dangerous.

Meanwhile Phyllissa Bilal says people are "fearful… in a constant state of trauma" because of the high levels of homelessness they see around them. It is not a fate they want to share.

By one estimate 3.5 million people in the US experience a period of homelessness in any given year. Another report has calculated that the US lacks 7.2 million affordable homes needed to house extremely low-income households. And even though hundreds of thousands of people are on waiting lists for public housing, the construction of additional publicly subsidised homes is seen as unlikely.

"There are very different perspectives in the US on how you help people who are in poverty," says David Layfield, who set up a website to help people find available spaces.

"There is a group of people who believe that you don't need to give a poor person anything, you just need to teach them how to work.

"We have a dysfunctional government in the US with two very strong policy divides… How do you get them to agree that a basic resource such as housing is necessary?"

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox