The Vocabularist: Speculation doesn't have to be 'mere'

- Published

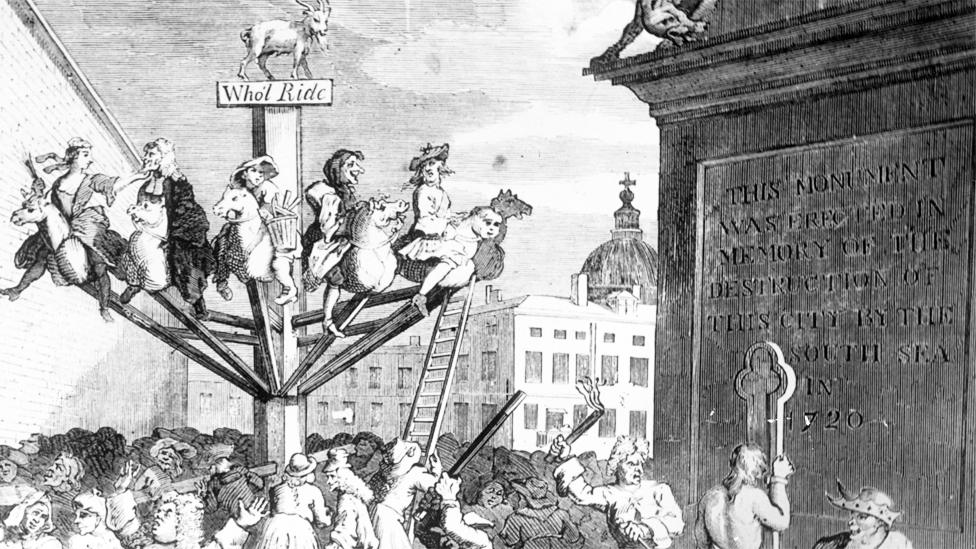

Part of Hogarth's print of the South Sea bubble, with speculators riding on a roundabout (labelled Who'll ride?) turned by the scheme's projectors.

The word "speculation" has gone from Roman scouts via religious mystics to political squabbles, writes Trevor Timpson.

"But this is mere speculation," says Watson in The Sign of Four, as his friend thrusts to the heart of yet another mystery.

"It is more than that," says Sherlock Holmes. "It is the only hypothesis which covers the facts."

That is a dialogue which plays out again and again in the news media. One side claims the other's view is based on guesswork only - calling it speculation, while the other says it is common sense.

Speculation comes from the Latin word specio, meaning look, which fathered a great tribe of words ranging from "spectacular" to "despicable".

In the Roman army a specula was a watchtower, speculatores were scouts or spies, and "speculatio" was what they did.

It came to mean examination of a subject, and the late Roman mystic Boethius used it to denote deep, reverent contemplation.

"People's souls are more free when they contemplate the mind of God (in mentis divinae speculatione)" he wrote. Chaucer used "speculacioun" in his English translation of Boethius's work.

In English it soon came to mean an opinion based on little evidence - but could be good or bad.

Reconstructed Roman gate and tower at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall. A watchtower was a "specula" to the Romans.

Francis Bacon, in the early 17th Century, wrote that an opinion of Plato was "excellent, although but a speculation".

During the 18th Century the word's specialised sense of a financial gamble came in very useful.

Amid the flood of business corruption involving the South Sea "Bubble" and other doubtful companies, Daniel Defoe wrote a cautionary tale "On the Evils of Stock Speculations" in 1720 under the pseudonym "Anti-Jobber".

Adam Smith, the oracle of 18th Century economics, wrote in The Wealth of Nations of the "trade of speculation" whose practitioners "exercise no one regular… branch of business" but enter or leave markets when they predict profits will rise or fall.

The financial use of the word was well-established while the general sense of an opinion based on guesswork was still rare, and still largely coupled with adjectives such as "vain" or "idle".

Some subjects are "too high to touch with speculation", Disraeli wrote

But it gradually became able to stand alone, implying a rather silly opinion.

In 1876 the Spectator reported that "speculation is rife" about Benjamin Disraeli's activities - but "we believe the simplest explanation to be the nearest to the truth. The Premier's health has been failing for some time."

Disraeli himself had warned in his novel Tancred that some subjects were "too high to touch with speculation". Many will continue to ignore this warning.

The Vocabularist

Select topic "language" to follow the Vocabularist on the BBC News app

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.