My secret life as a gay ultra-Orthodox Jew

- Published

Chaya, not her real name, is an ultra-Orthodox Jewish woman who is gay. Here she describes her struggle to accept her sexuality, and why she has to keep it a secret from those who would make her choose between her identity and her family.

I would lose everything if I came out. We are a tightly knit community and I think few people realise just how isolated we are. In the world I live in, being gay is the equivalent of being a bad person. It's seen as an evil desire that is completely unnatural.

People I have grown up with would wonder what else I could be capable of. Few would believe that I could still be religious and if I did eventually leave the Haredi community it would mean losing my job, my home and potentially my children.

It's just easier for everyone to pretend that there is nothing different about me. In fact, most people prefer to act as though homosexuality does not exist.

I was still at school when I first tried telling a rabbi I was gay but all he said in response was: "It's just a phase, it happens to a lot of girls."

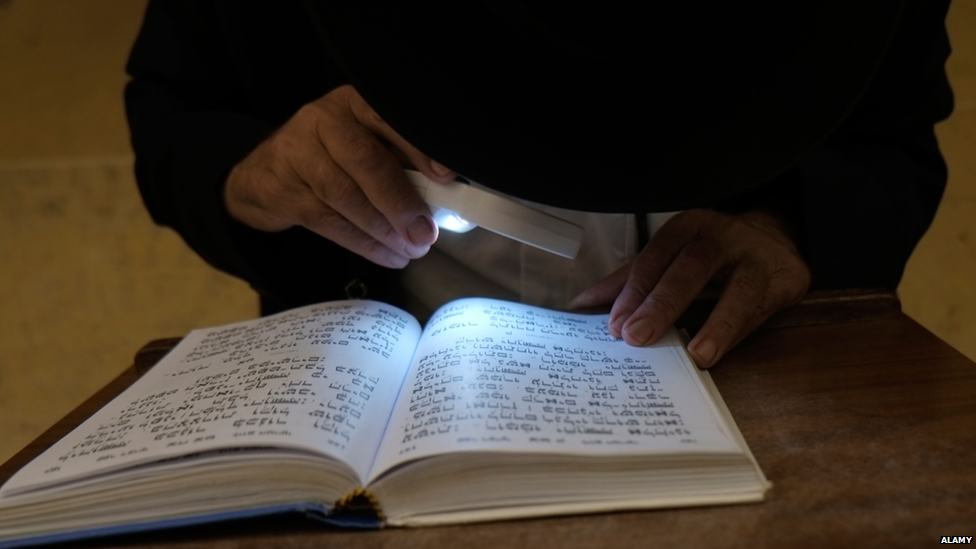

Haredi men in London

It's true that it's not unusual to have same-sex experiences when growing up. Our schools are completely segregated so girls and boys have little to do with each other from the age of three. The strictest families will even discourage brothers and sisters from playing together.

Children will experiment. I started when I was 12 but it was supposed to be something that we would all grow out of. I was different and as I got older my classmates started calling me a lesbian even though I was no longer doing anything.

It became increasingly difficult to ignore so I tried telling my mother when I was 16. It took so much for me to actually come out and say it but she just looked straight at me and quashed it immediately. We haven't discussed it outright since.

Soon after, my parents began to arrange a marriage for me. There is often a matchmaker involved in problem cases like mine. A successful engagement can earn them up to £15,000. But my family decided that they wanted to find me a husband themselves. Everyone was involved in the process except me.

Once the background checks were done and a boy was approved, we met for about half an hour. It took place in the dining room. His family and my family sat around a table talking awkwardly for a few minutes until eventually everyone else went out and left us to be awkward together.

Despite that, I think I was relieved to be engaged. I hoped that being in a committed relationship would finally help me feel that I belonged. But in the months before I got married, I started seeing a girl. We kept it secret and broke it off just before the wedding. It might sound strange but I still thought that I would be able to put it all behind me.

Chaya has worn a wig to cover her hair since her wedding day, in line with her religious tradition

As the wedding got nearer I began to feel more apprehensive. I knew that we were expected to consummate the marriage on the wedding night, although it does not always happen until the next day because the celebrations can go on until five in the morning. Even though contraception is frowned upon, I was put on the pill to make sure that I would not be on my period on the night. Neither my husband nor I knew what we were doing. He was too rough and it went on and on.

We are encouraged to have large families and I became pregnant quickly. If I had wanted to take the pill after the wedding I would have had to ask a rabbi for permission. I felt it would be unthinkable to ask for it before I'd had at least two children.

Once you are pregnant that child becomes both a hostage and your hostage taker. You are held hostage by your child. We are expected to have eight or nine children and I kept getting pregnant. My feelings built up inside me until one day I was walking down the street in a little cul-de-sac somewhere. There was so much noise in my head that I started saying "I'm gay, I'm gay, I'm gay!" out loud.

It made me feel like I had to do something about it. Eventually, I told my husband. I think he already knew I was gay but he'd convinced himself that it was just a latent desire rather than an integral part of my identity.

We still don't know what we are going to do. We have children together and a family set-up that works. If my husband and I separate we would lose all of that. I think we would all lose something if we broke apart so I may well stay married.

I hope my family can stay together, although I don't know what shape that would take. People have all kinds of arrangements. Rabbis have different ideas than some about how you should keep people together. In a case like mine, instead of trying to find a way in which we could both be happy, I think it will be just that I need to conform and fulfil my duties as a wife, which of course goes against the very grain of my being.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews in the UK

The Haredi community covers a wide variety of traditions.

The majority of Haredi Jews live in London - Hackney council estimates there are around 30,000 members of the community in its borough.

The number of ultra-Orthodox synagogue members has risen steadily over the past 20 years, external.

A third of Jewish children under five have Haredi parents, according to the Institute for Jewish Policy Research.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews are predicted to make up the majority, external of British Jews by the end of the century.

It's hard to live with the knowledge that if I just conformed, that this house would run so much more smoothly. It makes me feel like it's all my fault. But if being Orthodox Jewish and gay was not compatible then I don't think that God would have made me this way.

I was created like this with a plan, even if I don't know what it is yet. My faith has become a real comfort to me but it took me a long time to reach that point. My religion involves ritual, prayer, worship and acts of faith that are meaningful and I don't see why I should have to give that up.

I think it's a mistake to choose one aspect of your identity over another. This is not just about my sexuality. It's also about being able to be an individual within the community and about having a sense of self. The traditional role of an ideal wife is a strong woman who heads up the family and submits to her husband in areas of spirituality.

The woman is supposed to be the queen of the house. Her husband may still be learning the Torah full time in the early years of their marriage and it's often left to the woman to bring in most of the money. But although she might work outside the home, it's supposed to be in a refined way.

Modest dress is important for women in the Haredi community

Many women work as teachers in the community's private schools or as secretaries. There is a focus on the way you look because you are supposed to be attractive to your husband but not attractive to other people.

It's a fine line to tread. You have to be covered from your elbows to your collar bone to your knees, all inclusive. Some take it further and say that skirts should be mid-shin so that when you sit down your knees will be hidden. Your hair is always supposed to be completely covered and you're not supposed to draw attention to yourself.

Help and advice in the UK

Stonewall, external provides support and advice on coming out

Switchboard, external has an LGTB+ helpline on 0300 330 0630

Mavar, external is a "confidential service that helps people from the Haredi community explore new paths in life".

If someone does not fit in, people will talk about it. I'm ambitious, my home does not define me and I'm also not particularly feminine. Women usually have a large support network. Our extended families mean lots of sisters and female cousins who can help each other with the everyday tasks such as cooking and looking after the children. But they stop offering to help when you do not quite act like everyone else.

People have always called me a troublemaker. Some blame my current difficulties on my so-called lack of modesty. They say my skirt is too short and my tights are not quite thick enough. Even my hair is a topic of conversation.

In my culture, we always cover our heads in some way. It's usually with a wig if I am working, but the rest of the time I will use a hat or a snood. Underneath it all, I keep my hair cut short. Ironically, I can get away with it because shaving your head is seen as a sign of piety. Many women will have their heads shaven by their mother-in-law on the morning after their wedding. But my hair is something different - it's a style that I have chosen.

I suppose I have reclaimed my hair. But there is still a lot of my work to be done to reclaim my religion. There are a lot of people out there who are distorting it and it's not theirs to distort. Spirituality does not belong to them.

I own my religion. I'll always be Jewish - it's part of my identity, just like anything else is. I have even invented a word for it. They have ultra-Orthodoxy and modern Orthodoxy. But I call it honest Orthodoxy. I don't know, maybe in 40 years' time it will be a movement.

Listen to Chaya speak in The Salon on the BBC World Service.

As people become increasingly connected and more mobile, the BBC is exploring how identities are changing. As part of this, The Salon: Stories of women's identity from the hairdresser's chair, is speaking to people around the world.

For more stories go to the BBC's Identity season or join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag #BBCIdentity, external.

Produced by the BBC's Camila Ruz.

- Published6 April 2016

- Published2 April 2016

- Published1 April 2016

- Published14 March 2016

- Published1 April 2016

- Published1 April 2016

- Published29 March 2016