Will LSD ever be accepted as mainstream treatment?

- Published

Some researchers believe psychedelic drugs could be used to treat a whole range of conditions. But will cultural stigmas stand in the way?

Mention LSD and you might think of the 1960s counterculture - kaftanned hippies in San Francisco, or the more adventurous end of the Beatles' back catalogue, or the tragedy of Pink Floyd singer Syd Barrett losing his grip on reality.

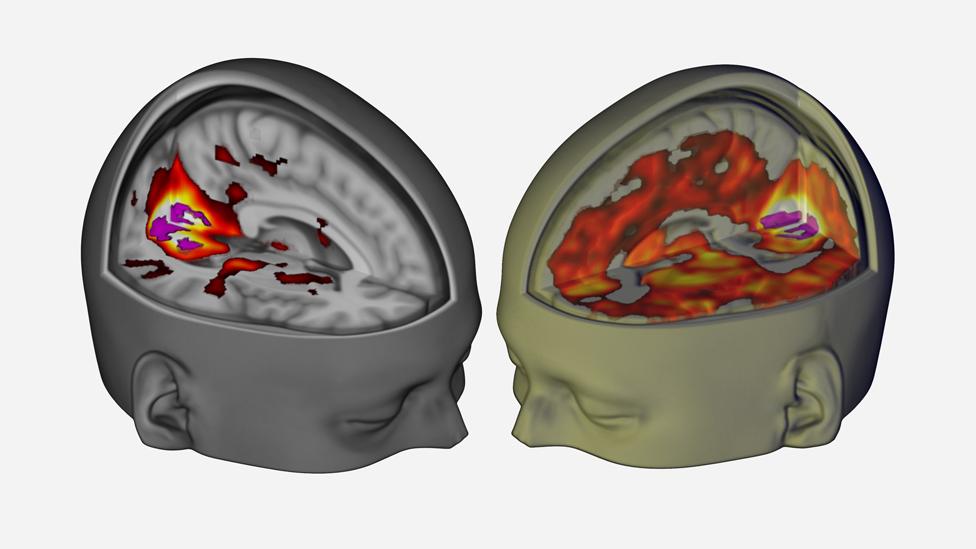

But for the first time, researchers say they have visualised how LSD alters the way the brain works.

A team at Imperial College London says they found it broke down barriers between areas that control functions like vision, hearing and movement. The study was with a small group - 20 subjects - but the researchers say, external it could lead to a revolution in the way addiction, anxiety and depression are treated.

For the past decade and a half, academics around the world have been studying whether psychedelic substances that cause hallucinations, changes in perception and mind-altering states could have medical benefits.

But this isn't the first time we've been here. Back in the 1960s there were high hopes for the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, too. Four major scientific conferences were held on the subject. Thousands of papers were published.

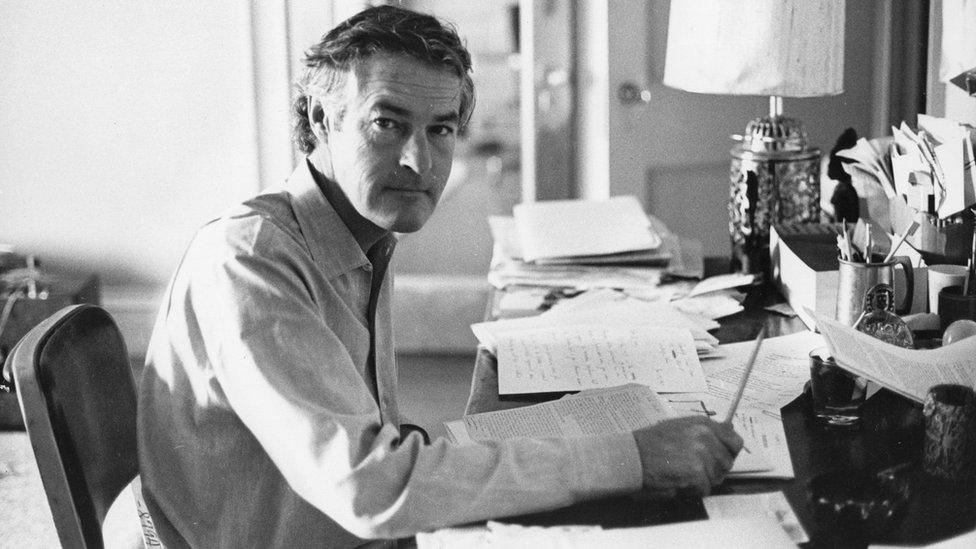

US academics experimenting with LSD use in 1955

But soon enough fears over the recreational use of LSD - or lysergic acid diethylamide, to give its full title - ensured research all but ground to a halt.

Jamie Bartlett, who made a recent BBC Radio 4 documentary on Psychedelic Science, says the cultural baggage surrounding LSD makes research into the subject extremely tricky. "The 1960s led to this huge clampdown on recreational drugs, so you are just starting out again," he says.

Hundreds of studies were carried out in the 50s and 60s into the effects of psychedelics in the US and western Europe. Researchers - including the Harvard psychology professor Timothy Leary - believed they could offer insights into the way the mind worked and potentially open the way to revolutionary treatments.

But it was not just in laboratories that people were experimenting with these drugs. LSD and other psychedelics were popularised by musicians, poets and artists and celebrated by the burgeoning counterculture.

Press coverage of the drug focused on bad trips, students throwing themselves out of windows and supposed moral degeneracy rather than any potential scientific advances. The shift in emphasis was exemplified by Leary, who in 1963 was sacked by Harvard and transformed himself from respected academic to advocate for turning on, tuning in and dropping out.

Timothy Leary 1920-1996

Timothy Leary (1920-1996), populariser of LSD

US psychologist, philosopher and advocate of psychedelic drugs, which he said could have beneficial effects in psychiatry and in the world at large

Began experimenting with the hallucinogenic substance psilocybin, while lecturing at Harvard in the early 60s

During the latter part of the decade he became one of the most famous figures in the counter-cultural movement, popularising the phrase "Tune in, turn on and drop out"

President Nixon once called Leary "the most dangerous man in America; he was arrested and imprisoned numerous times

All this led to a backlash. California was the first jurisdiction to ban LSD in 1966. Two years later psychedelics were banned across the US and, in 1971, the United Nations categorised them as a drug that could not be prescribed for medicinal use.

For a generation, serious research into the effects of psychedelic substances more or less came to a halt.

In 1999, however, researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, US, began a study in which psilocybin - the psychedelic ingredient in magic mushrooms - was given under careful supervision to people who had never taken it before.

Since the results were published in 2006 there have been more than a dozen research projects involving psychedelics. The sample sizes of the studies have often been very small, but the results have been striking enough to lead to calls for larger scale research.

At Imperial College London, researchers have been studying, external the effects of psilocybin on 20 people with severe depression for whom other treatments had failed. All the patients have shown some improvement in their depression, Robin Carhart-Harris, the leader of the study, told Bartlett during his programme. According to the Imperial team, two-thirds met the criteria for remission and after two weeks, the process showed double the effectiveness of standard treatments.

This image shows how, with eyes closed, much of more of the brain contributes to the visual experience under LSD (right) than under placebo (left)

A Johns Hopkins team found, external the drug dramatically reduced anxiety among people with terminal cancer. Another study, external of 15 life-long smokers found that 80% had given up smoking after three psilocybin sessions.

It's not absolutely clear how psychedelics could produce a therapeutic effect but it's theorised that a trip reduces function in a part of the brain called the default mode network that decides what enters into consciousness. Scientists believes this gives the brain the opportunity to break destructive patterns of behaviour.

It could be "an enormous aid in psychotherapy, particularly illnesses associated with very rigid thought patterns, like depression, anxiety, addiction and OCD, because LSD produces a looser form of consciousness", according to Amanda Fielding, head of The Beckley Foundation, which promotes drug policy reform.

This history of psychedelics, however, means they are never likely to be treated as just another substance.

Pink Floyd singer Syd Barrett suffered a major mental breakdown, thought to have been triggered by psychedelic drugs

There are also profound dangers to those who take them. A bad trip can end in a psychiatric ward. The drug education service Frank warns, external that LSD can have serious long-term implications for those with a history of mental health problems, and can be responsible for setting off mental health problems that have previously gone unnoticed.

And all of the results from studies on psychedelics have to be treated with extreme caution. It's hard to do a true double-blind study. The subjects are quickly aware they have taken LSD or a placebo, and it is often fairly obvious to the scientists. Efforts are made to counter this by using "active" placebos such as large doses of niacin to induce a tingling feeling.

Many researchers choose to exclude people with certain mental health problems. And it's also likely that the effects depend on the mindset of the person taking the psychedelics as well as the setting.

"LSD evokes such irrational responses, pro and con, that it's almost too hot a potato to deal with," Bill Richards, a researcher into psychedelics at Johns Hopkins, told Bartlett. For this reason, researchers tend to use psilocybin, which also delivers shorter trips and is more easily applied. Richards added, tongue in cheek: "One great advantage of psilocybin is that it's hard to spell and just doesn't get the negative publicity."

Help and advice

Bartlett says it's inevitable that the more science demonstrates the medical benefits of psychedelics, the more healthy people will want to take them as well.

"It was what brought the house down in the 60s," according to Carhart-Harris. "A lot of people may have missed out from effective treatment because of recklessness with compounds that should be treated with an appropriate level of respect."

Ultimately the challenges involved in researching psychedelics mean there will be a hefty bill to be footed before any sort of drug can be brought to market - and this will inevitably mean investment from the pharmaceutical industry.

Advocates for the benefits of psychedelics look to the way medicinal marijuana has become mainstream. Their best hope may be the passage of time as the 1960s recede further into history.

Follow Jon Kelly on Twitter @mrjonkelly, external

More from the Magazine

An undercover operation in 1977 smashed one of the most extraordinary drug rings the world has ever seen and changed British policing forever. What was Operation Julie?

Operation Julie: How an LSD raid began the war on drugs (July 2011)

BBC Radio 4's documentary Psychedelic Science is available on BBC iPlayer Radio here

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.